Published March 7th, 2022

Review

by Olga Pinjung

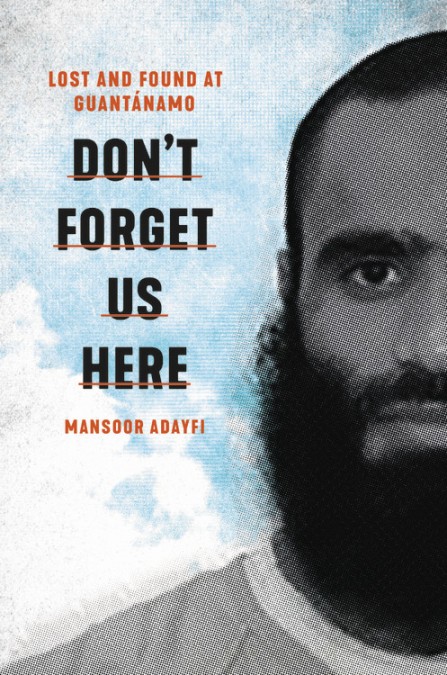

Don’t Forget Us Here is a book about endurance, brotherhood, suffering and finding happiness in hell: Guantánamo. It offers a painful yet hopeful and eye-opening view into the life of detainees, most of whom were captured, tortured, imprisoned without being charged with a crime, thousands of miles away from home, innocent.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks shook the whole world to the core. The government of the United States was desperate to capture and detain everyone who was allegedly associated with the tragedy. They were willing to do anything to quench their thirst for justice, thus their result-oriented approach ended up in the imprisonment of many innocent individuals who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Mansoor Adayfi was one of them. A Yemeni citizen who spent nearly fifteen years of his life at the Guantánamo Bay Detention Center without ever being charged with a crime.

His memoir Don’t Forget Us Here was published in August 2021. His intention with writing the book was to paint a picture of life at Guantánamo as the world had not seen before. He wished to portray the hardships and effects of physical and mental torture detainees had to endure as well as the rare but happy moments they shared with one another.

The first and most shocking fact about the book is its tone. Instead of being filled with rage and adverse feelings — as one would expect — it is quite the opposite. Adayfi accepted his fate and did everything he could to create a bearable life for himself and for his fellow inmates. Growing up in the mountain areas of Yemen as a member of a tribal society, he was raised to be an honorable, generous man who helps those in need. At the age of 19, he was taken to Guantánamo with these principles deeply instilled in him.

-salwan-georges.jpeg)

Adayfi takes the reader on a 15-year-long journey to a place everybody has heard of, but only a few could truly experience. He does not shy away from providing the readers with detailed descriptions of the various methods of mental and physical torture they used on detainees during interrogations. These parts of the book are difficult to get through yet make it impossible for the reader to put down.

Don’t Forget Us Here is a testament to brotherhood. The differences among the detainees were stark: men who came from more than forty different native languages, every age, from children to extremely old people — including a 105-year-old man — all they had and all that connected them was each other’s support and the hope that one day they would get out of there alive. Adayfi calls his fellow inmates his brothers and highlights the happy moments of hope and comradery which are woven into the story:

Each move, each interrogation, each beating brought all of us closer together despite our differences instead of pushing us further apart. This place called Guantánamo had created a brotherhood among us and now we looked out for each other wherever we were, no matter who we were.

They were forced to realize early on that they could not reason with the guards and the administration because they refused to listen to their stories. They had to rely on each other. When the detainees’ request for the treatment of a brother’s bad tooth was ignored, they resorted to what proved to be one of the only effective ways of protest at Guantánamo: hunger strikes. Detainees all over the detention camp joined in and refused to eat. It was the only means they could use to achieve some minor but significant changes.

Brothers stood up for each other when one of them was in trouble. Occasionally, they also shared some cheerful and fun moments. Even solitary confinement could not keep them apart; they sang and played pranks on each other and the guards. Their conditions were slightly improved in 2010, when they were allowed to spend the day in a communal area and attend classes. Once a week, they were allowed to paint and write with the help of instructors, all while being chained to the floor. What is more, detainees held classes for themselves covering basic subjects such as cooking and marriage. They did not have any equipment or a kitchen, but it did not stop them from teaching each other the basics of preparing a meal, however theoretical it was. Several detainees were teenagers when they were captured and they had no experience with women, so older brothers took it upon themselves to educate the inexperienced population of the detention camp on the proper treatment of women and what it was like to love somebody. These candid moments of friendship and sense of community meant the beacon of hope for them. As Adayfi recounts, “our final class was dedicated to the biggest day in our lives, the marriage day. ( . . . ) It was a lovely time that returned us to our homes and families, if only for one night. We lived in a golden age, but it was still hell. Even in that hell, we created small, beautiful moments that made us feel alive again.”

Apart from showing the life of detainees, Adayfi considered it important to write about the effects Guantánamo had on the staff, in particular on the guards. He admirably acknowledges the fact that guards did what they were ordered to do, they did not have a choice. On the other hand, some were extremely cruel and disrespectful to them: they would beat them or desecrate the Qur’an. At the same time, many others took the time to get to know the detainees and even helped by talking to them, giving them books and dictionaries. Guards and nurses spent their days and nights in the presence of detainees, they were part of each other’s lives, to a point where they played jokes on the new guards:

Sometimes the block sergeant wrote things like HAND EATER or FLAME THROWER on our cards and made up crazy stories about how a brother had eaten guards’ hands or could breathe fire. ( . . . ) The new guards would believe anything after what they had been told about us during their training. Usually, they figured things out in a couple days, and by the time they rotated out, they were joking around with us.

Don’t Forget Us Here is a story about human beings trying to cope and survive. Mansoor Adayfi masterfully finds the balance between the terrible and the joyful, the painful and the humorous. He does justice to the detainees by sharing their stories, including the hardships, and suffering. His story is a tribute to all his Guantánamo brothers, those who were released, those who lost their lives there and those who are detained to this day.

I highly recommend reading Don’t Forget Us Here to everybody because it is crucial, even today, more than 20 years after 9/11, to raise awareness for the mistreatment of detainees, the violation of human rights and most importantly, the fact that people are still imprisoned at Guantánamo. It is heart-breaking to read at times and it brought out a sense of failure in me because, despite living thousands of miles from the United States and Guantánamo, I felt responsible because we, as humans, grossly failed these people. They became victims of a system that was driven by fear and desperation. These innocent people lost ten, fifteen years of their lives they will never be able to get back. Those who have been released over the last few years should be allowed to go on with their lives, and those, who are imprisoned to this day without charges, should be released. Since his release, Adayfi has dedicated his life to telling his story and speaking up for those who are still detained at Guantánamo (360). His benevolence is praiseworthy, so is his appreciation of the positive and cheerful moments he lived thorough at Guantánamo. Nobody should rob themselves of the experience of reading Mansoor Adayfi’s Don’t Forget Us Here.

Nationality: Hungarian

First Language(s): Hungarian

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by:

Comments on "We Will Not Forget: "Don’t Forget Us Here" by Mansoor Adayfi — A Review"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login