Short Story

by Daniel Ogba

1.

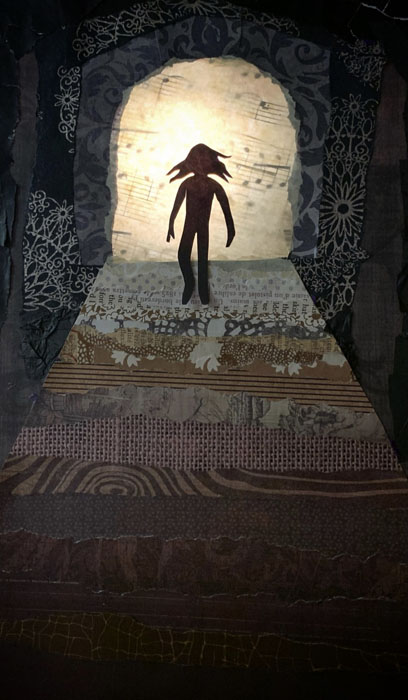

Trouble wore a plain black t-shirt and facecap the day it visited Flat 6.

Kainayo made sure the key turned twice in the lockhole, clicked secure, before she hid the bunch underneath the wooly green foot mat and left for Ogige that morning. The sun was barely out that Saturday, but the sky was an endless cerulean sheet, the streets still clogged with rainwater from the night before.

Just outside the compound’s gate, a group of young men were lifting from the road corrugated aluminum sheets that the storm had blown off the roof of Okey’s local chemist shop. She had stopped briefly to sympathize with the man who, visibly frustrated, lamented his ill fortune to all who walked by. Kainayo had lazily put on a faded pink trouser and an ash blouse, wrapped a turban around her head to hide her ruly mess of hair. She did not put powder on her face; she slipped into her akpoola sandal, something that could buoy her with safety through the market’s muddled paths.

When she pressed her face into pity, clasped her abdomen to say, “Eii nwannem, it’s a tragedy. Just bear, eh,” after Okey emptied himself of his woes, Kainayo was careful not to lean in too close to the man’s face. That morning, she had only swished her mouth with saltwater, wiped her face and underarms with a wet towel, not in any way bothered about hygiene. How many of the other women washed themselves clean before crowding the tail of the Datsun truck to offload boxes of fresh fish from the stock? What did it matter anyway, if she smelt of cocoa before leaving, since she would return reeking of fish and dried sweat? Besides, she didn’t even plan on staying long at the market, away from home — away from her daughter.

Before she left, Kainayo had said to Gracie through the window, “if anybody comes knocking, tell them your parents are not around, you hear?”

“Yes, mummy," Gracie replied, her expression sullen.

“If the person asks when they’ll be back, tell them soon, you hear?”

“Yes, mummy.”

And although Kainayo had secured the doors herself, and there was no other key to the entrance except the one she had, she told Gracie: “On no account should you unlock this door for anybody, you hear?”

“Yes, mummy,” the little girl responded.

“Good girl,” she said, tugging at her cheeks through the metal protector. “Mummy will be back before you know it, and she will buy ice cream for you, eh.”

But when Kainayo walked home at past noon, the cool from the ice cream in her purse tingling her fingers to a numbness, she found that the window was half-closed and that, more strangely, the door she was sure she had locked before leaving was ajar. At first, it was funny to her. An expensive joke. She rubbed her eyes to make sure she was seeing correctly. She did not enter the house immediately. She scanned the doorstep to see if something was off: the wooly green foot mat remained unmoved, not a speck of dust on it, just as she had placed it that morning after she’d swept the flat, the keys still underneath. Somto’s cane stool remained upturned without use. The aloe vera vase still sat at the extreme corner of the balcony, the long broom for cobwebbing the ceiling tucked behind it; her’s and Gracie’s shoes were arranged to the side. Did Somto come home? Her husband wouldn’t be home till Monday morning, when his shift at the glass manufacturing industry in Ughelli would have been completed. And even if he did come home earlier than expected, he would have kicked off his shoes at the doorstep. And he would never leave their door open like that, not even on evenings when the smoke from her deep-frying fish in the kitchen choked the flat. She dropped the Bagco bag she had returned with at the door, the contents — onion bulbs, sliced red meat and vegetables she’d bought after the day’s sale at Ogige to make Sunday stew — peeking out from the bag. Kainayo hastily ran into the house shouting, “Gracie, Gracie!” She flung open the doors to each room, checked the toilet, the kitchen, the backyard. Gracie was not in the house.

“Where this pikin go nah?”

Kainayo pulled the turban off her head and her hair sprung disheveled into a semi-insane mood. Perhaps, Gracie had gone to play with their nextdoor neighbor, Mama Emeka's kids; Gracie might have asked the kids to help her unlock the door. Juvenile mischief, which wasn't new after all, just children being children. Kainayo went to the neighbor's. Her kids were watching television in the sitting room, no, Gracie didn't come over, Mama Emeka said. She ran back to the flat, double-checked the rooms, and only while pacing the sitting room for what was probably the millionth time did she notice Gracie’s blue linen doll lying on the carpeted floor, its neck ripped open and white stuffing oozing from the cut. She picked the doll up; examined it this and that way for clues. Nothing.

It was quarter to 3 p.m when it occurred to Kainayo to call Somto. Her heart had already begun to skip beats, dark clouds thickening around her skull, and her legs found it so much duty to support her frame. She retrieved her phone from the purse, swiped at the tension beads forming on her forehead dripping a stinging sensation into her right eye. She called Somto’s number. The first time, the customer service lady’s voice had said: “The number you dialed is not reachable at the moment. Please, try again later. Thank you.” The second time, the woman said Somto’s number was busy. The third time, before it finally connected, she broke into an impatient sobbing fit as the customer service lady proceeded to recite slowly the COVID-19 precaution protocol.

“Baby,” his voice came. “What’s the matter, Kayi?”

“I — Gracie, I — I,” sobs, “It’s Grace, I —”

“Calm down, Kayi. What’s wrong with Grace? Calm down and talk to me, babe.”

Kainayo heaved loudly, snot ran from her left nostril to her upper lip, passing into her mouth as she spoke.

“I can’t find Gracie at home.” She paused, assessing the words. “I went to the market and returned home, and I can’t find her here. I locked the door, Somto, eh. I made sure I locked the door.” She wiped her lips with the back of her free palm. “I can’t find our daughter.”

“Relax. What do you mean? Did you check outside, did you look around the compound, maybe she’s playing with the other kids, Kayi? Have you checked?”

Maybe. Kainayo recalled then that she had passed a group of kids playing a game of Swell in the front yard. She had been too in haste to notice whether or not Gracie was in their company. She hung the phone up, hurried outside, grabbed each child and stared in their faces while questioning them. “Have you seen Gracie? Have you seen my child?”

2.

Kainayo had shrunk three-quarter times her size by the time Somto walked into the cramped sitting room drenched to his briefs. It was barely past 8 p.m. She was spread like old cloth on the floor, flanked by two women, their neighbors: Emeh, who owned the provisions store at the junction, and Ifee, the caretaker’s housewife. Two policemen hovered above her, one of them writing whatever on a pad. Somto nodded to the neighbors’ greetings at the door, then rushed to crouch before Kainayo.

“Nnem,” he said, holding her chin up to meet pepper-red eyes glazed thoroughly in the beginnings of a fresh bawling. The two women distanced themselves. Kainayo’s shoulders heaved, and even though she opened her mouth to speak several times, nothing came. Just hoarseness and hiccupped breaths. “Ozugo, ozugo.” Somto culled her head into his chest in a wet embrace.

“Are you the husband?” The policeman with the pad asked.

“Eeh-ye.”

“May we speak with you outside, please?”

Somto followed the men out to the balcony, and the women flocked to Kainayo’s side, never leaving her on her own.

Outside, the policemen had asked Somto if he owed anybody money, no matter how little. His gaze steered into surprise under the lamplit balcony. He shifted his gaze away from the men’s faces to their tall, ghoulish shadows cast across the concrete, then back to their faces. Were they being serious? They waited till he opened his mouth to talk, then the policeman with the pad put pen to paper.

“See, I am a factory worker. I earn not enough to put myself and my family through. So, yes, I borrow money from people from time to time. And I pay, but things haven’t been easy this COVID period with the lockdown.”

“Do you know anybody you owe who would resort to this to get their money back?”

“Hmmm. Why would anybody take my daughter because I owe them? That is evil.”

“People are evil these days, you know? Last two weeks, shebi a man from Obollo took his debtor’s wife into his house, pending whenever the man paid him in full.”

“What’s worse?” The other policeman interjected, “They say he’s been sleeping with the woman every night for the past two weeks! Somebody’s wife.”

“Matter tire pass Mathias, my brother.”

“People dey evil, forget o.”

Inside the packed house, the women offered consoling words, wiped at the tears as they rained down Kainayo’s face with the hem of their scarves. When she heaved her shoulders, they heaved theirs too in unison. When she stretched her hands to her knees as the grief of a missing child tweaked her spine, they did the same. They performed her sadness, not mockingly. It was their saying: we feel whatever you feel, Gracie is our own daughter, too. They became extensions of herself, as if by doing so the grief would dissipate: widen the surface area, rock the mass back and forth, to and fro, swallow the pain. But the mass remained as solid, as heavy, and sat wedged in a small space in Kainayo’s chest, near her heart, metastasizing. With each moment, her breathing slowed and slowed till the tip of her fingers began to grow cold. Yet, the women stayed with her. Even after the policemen had returned inside to say, “We’ll do our very best to find you your child, eh, Madam?” before leaving. They stayed. Even after the flat had emptied of flabbergasted neighbors, and parents tucked their kids in bed, locked their rooms, and put the keys under their pillows. The women stayed.

“Have you had anything to eat yet, my dear?” Ifee asked. But Kainayo still did not know how to form words. Her bones had numbed like a chicken left out overnight in the rain. “You haven’t eaten anything yet?”

“She doesn’t look like she has, shaa,” Emeh said.

“Aww, my dear. Let me rush to the flat and get you something. I have nsala. You will eat nsala, won’t you? At least to chase the cold, eh?”

Kainayo stared forward. “I’m not hungry,” she managed to say.

“Iya’sikwa! Come off it, biko. And you need to change too.”

“I’ll help her change,” Emeh said. “Please, help me tell Donatus to lock the doors very well o, that I’m sleeping over.”

Ifee returned not long after with a small, steaming flask of nsala soup with fat chunks of goat meat, and molded yam balls floating in the broth. She said, “Oya, oya, my dear. You can’t be starving yourself. If it’s about Gracie, she will surely come back home. The devil is just a cursed trickster — don’t fall for his dirty plans.”

“Eziokwu,” Emeh added. “I remember it was during the election season last year that they kidnapped Nkwoagu's daughter as she was on her way home from school. But the woman prayed and prayed. Imakwa, just as the kidnappers were about to cross the Asaba bridge, their car refused to move again.”

“You don't mean it!” Ifee said. She was kneeling before Kainayo, unwrapping the semolina from its white nylon.

“I'm telling you. The men, they tried and tried, the car wouldn't budge. Until one of them asked the girl to get down, that was when the car came alive and sped off. They didn't even stop to pick the girl again. It was a good Samaritan that picked her and drove her back here to Nsukka.”

“What God cannot do does not exist, my sister,” Ifee said.

“At all o. So, God is in control, nne.” Emeh turned to Kainayo. “Try and eat something.”

And Kainayo had tried. But the grief had occupied a portion in her stomach, rearranged her intestines, such that when the fifth bolus of semolina slid through her throat, the grief arrested its journey halfway and sent it back the same way it had entered. Her entire body revolted, sent from her turned-out throat five semolina bullets slimy with mucus, and gray liquid flying across the room — some of it landing in Ifee’s eyes. Emeh, sitting by her side, rubbed Kainayo’s back, said, “Ndo, ndo.”

“God is in control.”

3.

By morning the world had turned in on them completely. Outside Flat six, the air seemed pristine in the aftermath of the night’s downpour. The sky had begun to crack with sunlight when Somto’s eyes opened to the scathing brightness of it blatantly pouring into the sitting room, awash over his body. He was used to watching the sunrise on Sunday mornings from the cane stool in the balcony, with Gracie climbing into his lap naked, her hair brushing against his eyelids, mouth, nose, wrapping wiry hands over his neck, saying, “Good morning, Papa.” He would tickle her armpits in response and Gracie would burst into a raucous laughter. He was used to Kainayo screaming all over the house, in his words, “disturbing neighbors’ peace,” for Gracie to quit playing around, else they would be late for the mass at St. Joseph’s. The sun was still rising, and it angered him. He wanted to drag himself up from the sofa where he lay the night before and yank the curtains close. He wanted to seal off every inlet for even the tiniest beams. But, his body was stiff like it had been concrete-nailed into the sofa. He no longer could feel where his arms stopped or where that of the upholstery began.

He’d only felt this way once, when his mother died in his bedroom seven years ago. She had been severely ill, but she had begun convalescing. That morning, they were sitting on the bed, chatting about female relatives that had married finally after long years of searching; the ones that had turned out non-entities, bound by a strong agwu preventing them from progressing; an uncle threatening to covet this or that land; his going back to the university to complete his engineering degree because, he could never tell, the certificate might be his saving grace in the future. She said she was feeling a bit lightheaded, that the walls were spinning and she noticed everything in too bright colors. She started rubbing her temple minutes later, groaning, and before Somto could ask, “Ogini? What’s wrong?” his mother had stopped breathing. Just like that. And for days that stretched into weeks, he could not leave the sofa. His body from legs down simply shut down. He didn’t eat for the first five days, and just so little through the remainder of his mourning period. And even when Kainayo offered to clean him up, he shrugged her away.

Gracie came to them a year after the same day his mother had died, so they christened the child after her. The child changed Somto’s life. It was on the day she came into this world that he bought his first car — a navy blue Mazda tribute. He was drawn to her; the way her eyes glittered, like round orbs, rheumy and capsuled in shiny pink lids. Gracie was his luck charm. Now? The world had capsized upon him, pried open his hands and grinded all his luck to dust.

Somto was resting on that sofa when the policemen came by in the evening, but without news except, “we’re doing the best we can to find your daughter. Exercise patience with us.” Kainayo folded into a corner of the leather armchair, not filling out the space, her eyes watching past the men standing in the center of the sitting room. The muted television flashed in successive clips of a crowd: clustered bodies damning the pandemic guidelines, wearing colorful ankara uniforms with a politician's large head printed in circles on the fabric. Under the blazing sun the crowd gyrated, waved banners and brooms, symbols of the politician's party. The politician, in contrast with the crowd, was masked and surrounded by mean-faced men with loaded chests and rifles. He mounted the podium, tapped the microphone, and as soon as he opened his mouth to speak, the screen faded to black. The room was replaced with a different kind of stillness.

“Do you have a recent photograph of your daughter?” one of the policemen asked.

“Of course,” Somto said. He stood up from the sofa and shuffled to the television shelf. He pulled the family photo album from the stack of engineering journals, dusted the jacket, flipped through the pockets till he arrived at a photograph of Gracie. “This is from her birthday a year ago,” he said, tracing a finger through the corners of the child's lips stretched in a smile. He passed the album to the policeman. The man stared at the photograph and sighed.

He said, “I'm aware how difficult this moment is for you, sir, and your wife. We'll be sure to place adverts on every major TV station, your contacts as well, in the news, just in case anybody knows anything of her whereabouts. It's the little we can do. That doesn't mean we're relenting in our own personal investigations, but you can never tell.” The policeman freed the photograph from the transparent nylon and folded it into his breast pocket.

Somto thanked the men, stood up, walked into the bedroom and returned with a brown envelope which he squeezed into the policeman's hand. He thanked them, again. Kainayo sat in the chair, unmoving still, head bowed.

Just as the men were about to leave, Emeh wandered into the flat, dragging her househelp, Ekanem, behind.

“Good neighbor,” she greeted, “my girl here has something to say, gbo?” She turned to face the girl. “Ngwa, speak. Tell them wetin you tell me.”

“What is the matter?” Somto asked.

“I see him,” Ekanem spoke.

Somto’s eyes widened, and Kainayo stirred in the chair. “See who?”

“The man. Him wear plain black t-shirt and a facing cap.”

“Did you see his face?” One of the policemen asked.

“No o,” Ekanem answered. “The facing cap dey cover him face and me I was from far.”

“Wetin you see?”

“I see as him carry Gracie for shoulder enter car, come drive comot. I been think say na their family member,” she said, pointing towards Kainayo.

“What car?” Kainayo’s body sprung from the chair, lurched forward to Ekanem, seized her by the collar of her shirt. She asked, her voice like from a nightmare, “What car?”

“Na jeep, madam. Black jeep.”

And then her heart broke further, pain so exquisite rankling her blood; an ironsmith, standing at the threshold of her rib cage, chiseling away with vim bits after bits of her heart, till what remained of the organ could fit in the balled fist of a toddler. To have a missing child is a tragedy on its own, but to know that the child was taken from your own home? How does one live with that? Why did it have to be her family, her child? It made no sense. It was her fault, she thought. In that moment, her mind, treacherous, conjured pugnacious scenarios of her daughter. Gracie: on a table in an uncompleted building, bloodied, legs pieced apart from hands apart from head. Or: zipped inside a suitcase in some politician’s closet, coughing out crisp currency notes. She’d heard such tales, of politicians, blood-thirsty and blinded by ambition, recruiting young children during the election season for rituals to boost their chances. The scenes kailedoscoped wildly in her head in specific details, the gore of it causing her limbs to vibrate. “It is all my fault,” she said, her voice a whisper. She repeated the words again and again, her voice rising.

“What are you saying, Kayi?” Somto asked.

“I should have taken her with me. I should have taken her to the market with me. She wanted to go with me. She didn't want me to leave her behind.”

“Don't blame yourself, please. Don't,” Somto cautioned.

“She didn't want me to leave her behind, Somto, yet I left her. She was sad. It's all my fault.” Kainayo crashed to the floor, wailing all over again. She did not hold herself, not even when her wrapper loosened around her chest to her waist. Somto hurriedly pulled it back in place. The policemen excused themselves. For Kainayo, the world had unclothed her; there was nothing left to hide.

When bathing in a stream, do not take off your clothes

Do not hang them on a tree

Abiriba will take them

The madman will take your clothes and leave you unclothed.

4.

The children from the block rosary came each evening at 5. Kainayo no longer kept track of how long they’d been coming for, but their presence soon became, unexpectedly, the most interesting part of her days. She would perch on a stool behind the half-closed sitting room curtain and watch as they arrived, rosary beads around their necks or wrapped on their wrists. The girls in blue scarves covering their foreheads with its tail pulled back to touch their waists like a wedding veil. They would set a table under the orange tree in the front yard, spread white satin cloth on it, and place a statue of the Virgin Mary on the table with a framed photograph of Gracie beside the holy mother of God. They would kneel in front of it and begin with “in the name of the father…”, signing the cross. Kainayo would watch each child keenly: eyes shut in deep devotion, hands clasped together at their lips which moved in perfect synchrony as they recited the Hail Marys and Our Fathers. And she would imagine Gracie was somewhere in their midst, scanning the scarfed heads of the girls, finding her daughter sucked in profound religion. She would blink, once, twice, Gracie would vanish, and she would maliciously wish it had been any of the children from the block rosary that had gone missing, not her Gracie. Why were they spared, these children? Were they any better, any less vulnerable than her daughter simply by wrapping rosary beads around themselves? Was Gracie marked?

Mkpurumma, her sister had said, “God hears the prayers of children faster, you know? Their innocence is still intact, unlike us adults. Imakwa, when I was still child-hunting, I went for their evening prayers at the Chapel of Immaculate Conception with Iyke for three months straight till God did it for us!” Kainayo could almost touch the fascination spreading in her sister’s voice. “It was a miracle, nne. After eleven solid years without an issue. Who would have thought?” They were sitting at the dining table. Under the flickering yellow flame of a kerosene lantern, Mkpurumma shelled in a tray the melon seeds she'd brought along from Awka where she lived with her husband and twin boys. It was Mkpurumma who, during the one week she stayed, cooked elaborate meals to cheer her sister up. It was she who booked the masses at the Catholic church and, when Kainayo would not even attend them, invited the children to host their prayers in the compound instead.

Kainayo would watch the children and imagine their prayers ascending expressly into heaven, sliding warmly between God’s ears. Why was he taking long to respond? She had counted two weeks and three days before she stopped counting. She would listen to the children hymn melodiously, some of the tunes a blurred memory from her childhood when she still attended block rosary, tied her scarf like the girls, and thought she would become a nun. When the prayer leader announced, “For Gracie, our dear sister: May the light of Mary, mother of the lost, guide her home,” Kainayo would get down on both knees, sign herself, and pray somehow her daughter would return to her. She would share cabin biscuit packets and Caprisonne amongst the children after the prayer had finished.

God finally answered her prayers when one morning she begrudgingly took a phone call. A woman on the other end asked if she was speaking with Kainayo Okogwu, that she knew the whereabouts of her missing daughter.

“Where did you see my daughter?” Kainayo asked, her heart slowly quickening.

“Ehh — it was close to one uncompleted building like that,” the woman said. “But you have to drop something before I can give you the exact location.”

She called Somto to speak with the woman over the phone and, although he felt half-hearted about what the woman was saying, for his wife’s sake, asked the woman to name a price and send her bank details. The woman’s number went straight to voicemail after he transferred his salary of two months to the destination account. They were unable to trace the phone number.

Kainayo did not watch the praying children from behind a half-closed curtain the next evening. She came out of her flat as they were about to announce the second luminous mystery of the rosary, a loosely tied wrapper hugging her body. She walked straight to the laid altar, dragged the satin covering, sending the statue of the virgin Mary and Gracie’s photograph flying off the table and shattering on the concrete floor. Her eyes a wet red, Kainayo barked in a voice that did not belong to her: “Don’t you have errands to run for your parents? Go home, osiso. And never come back here!”

When Somto came home three months later with his umunna, yards of black brocade, and a coffin in his boot, Kainayo could not believe that he had, at last, resigned to hopelessness. She refused to wear the black. It would spell a finalizing of some sort — Gracie was gone forever. She couldn’t — wouldn’t — accept that. She saw Gracie in varying vignettes every night in her sleep, running in circles and circles, but never getting close enough for her to hold. She with Gracie at Ogige market; a stampede; Gracie slipping from her grip in the mad rush, engulfed by the crowd. Gracie, stooped in a corner in an uncompleted building, crying blood.

Somto huddled close to her that night, said, “Kayi, I think it’s time for us to let go. God knows best.” She swerved her body away from Somto, sat upright on the bed to stop the bile in her throat from rising further.

“Gracie is coming home,” she said, facing the darkness. “I know it strongly in me, Somto. There’s no way I’m putting a picture in a box, pretending that it is my child, mba.” The tears streaked quietly down her chin, and she did not resist when Somto wiped the wetness from her cheeks, pulled her into him, said, it’s ok, it’s ok. She wasn’t sure, but she might have heard him also say between measured breaths, we can have another one.

Gracie was put to rest at a clearing in their backyard. While her husband, his umunna, the church and friends lowered an empty coffin six-underground, Kainayo locked herself in Gracie’s room, sewing close the rip in her daughter’s plush linen doll.

5.

A week passed after the burial, and Kainayo began cutting pieces from her old wrappers to style dresses for the doll. She would sit on the cane stool in the balcony and wash it with water and Johnsons’ baby soap, the same way she had washed Gracie as an infant. Then she would smooth vaseline down its back, dress it up, and walk from one neighbor’s door to another declaring, “My Gracie is back o, come and see.” Kainayo never let the stuffed thing out of her sight. It laid between she and Somto while they slept at night. He thought it a temporary mechanism of grieving she would snap out of. One time, in the middle of the night, she bit Somto’s shoulder, almost drawing blood, because he had mistakenly rolled atop the doll in his sleep.

Another time, she sat on a low stool in the sitting room sobbing, the doll in her hand. When Somto asked what the problem was, Kainayo said, “She doesn't want to eat.” He tried to be sweet, so he responded, “Maybe she isn’t hungry yet.” But sweetness rarely cures delusion. When Kainayo attacked Okey, scratching the skin off his eyelids, revealing the fine white which furiously blushed into red, because he said he had no drug for her child’s fever — that she was the one in need of medicine — Somto knew he had to act. And while she napped, he looped a chain around her feet to that of the bed. Kainayo had tried to wrest herself free when she awoke, but the chain rattled and grated her ankles.

“Kayi,” Somto held her face, staring into her brown eyes bulging with the veins as if she had become heavily possessed. “You’re not well, babe. Stop strugg —”

“Shh — listen. Do you hear that?” She asked, her eyes wildly scanning the ceiling.

“Hear what?”

“The baby. I can hear the baby crying.” Kainayo started sobbing. “I can hear our baby crying, Somto. She needs me. My baby needs me.”

Appeared in Issue Fall '22

Nationality: Nigerian

First Language(s): Igbo, Pidgin English

Second Language(s):

English

Das Land Steiermark

Listen to Daniel Ogba reading "When Trouble Calls Home":

Supported by:

Comments on "When Trouble Calls Home"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login