Short Story

by Murali Kamma

The first time he saw Jagan was during an improvised cricket game in the spacious courtyard of an ancient, weather-beaten but stately house owned by Ravi’s maternal grandparents on the East Coast. Ravi wasn’t 15 yet, and Jagan was — as he later told them — 16, the same age as Ravi’s sister, Radha. Every year in the dying weeks of a blistering and humid summer, the siblings had accompanied their parents to this sleepy town, where, if they were lucky, the rains would have already brought, along with greenery and the smell of moist soil, much-needed relief.

Ravi, playing with his sister and their father, held his bat expectantly. Jagan was sitting under a jackfruit tree from which prickly, sticky fruit dangled like green lanterns. Although they hadn’t spoken yet, Ravi knew that he was the son of a recently hired woman who worked for his grandparents. Swinging his bat, Ravi was more tense than usual, conscious of Jagan’s intense interest in the game. He didn’t want to disappoint their only spectator. Standing in front of the sawed-off stump of a coconut tree that had collapsed in the last cyclone, Ravi waited for his dad to bowl the next ball, hopefully at the relaxed pace he preferred.

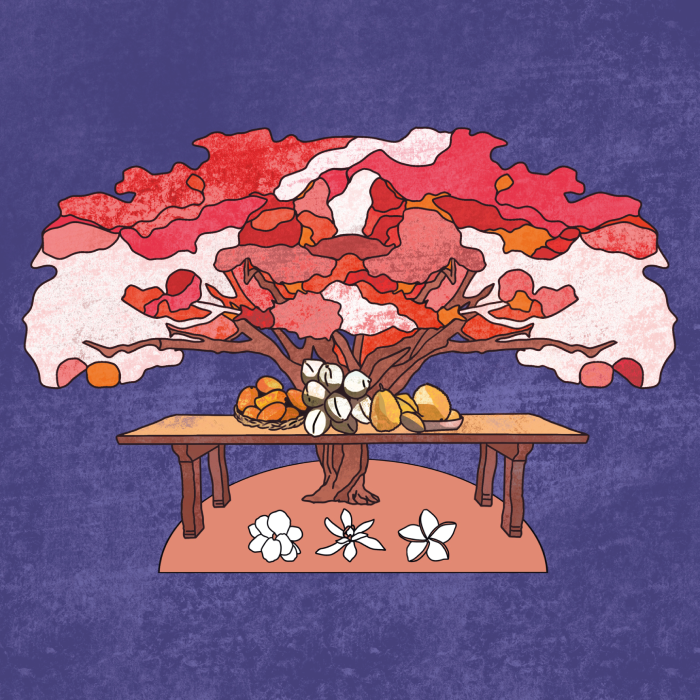

The wall behind the stump was their wicketkeeper. Radha, whose interest in cricket was limited, had been coaxed to join them — and as the sole fielder, she stood at a distance in the courtyard, where the grass was growing again, albeit unevenly, and the sweet-smelling jasmine, frangipani, and champak flowers were in bloom. The mango and jackfruit trees had yielded delicious fruit, while the surviving coconut tree swaying over the covered well in the corner still provided juicy, thirst-quenching coconuts when they needed them.

Yes, Papa was going easy on him! Stepping forward, Ravi opened the face of his bat and thwacked the spinning red ball, relishing the popping sound of the willow. But then he watched in alarm as it hurtled towards the boy, who remained seated and seemed unconcerned. Jumping to his feet at the last moment, he caught the ball with surprising alacrity.

“Brilliant catch!” Papa yelled, clapping. “You’ll be a good player. Come, join our game instead of just watching from there.”

Ravi was annoyed. Did this mean he was out? Counting the catch would be unfair — and fortunately, his dad agreed, allowing Ravi to continue as the batter (“batsman,” at Radha’s suggestion, had become “batter”). Jagan, initially shy, said he’d never played cricket before. But he joined them and proved to be a quick learner. A natural athlete, Radha later observed. An agile runner who displayed amazing reflexes on the field, he could also hit the ball with ferocity.

Ravi warmed up to Jagan, seeing him not as a competitor but as a player who brought excitement to their game. After a while, the sun climbed higher in the sky, sharpening the glare and heat, making it too uncomfortable to linger outdoors, let alone play cricket. Calling off the game, they headed indoors to wash up and have lunch. Jagan, having informed his mother, was saying goodbye before heading home, when Papa asked him to stay for lunch.

Looking confused, Jagan said he usually ate with his father.

“You can eat here today,” Papa said, smiling. “I’m sure your father won’t mind. You played with us, and now you can have lunch with us. Wash your hands and join us at the table.”

The wooden table next to the kitchen seated only four people. Ravi and Radha’s mother, Amma, was with her invalid father in his room, but their grandmother and Jagan’s mother, who had been getting lunch ready, emerged from the kitchen with a jug and dishes in their hands.

“Why are you sitting here?” Jagan’s mother said sharply. “I’ll give you food to take home.” More than baffled, her expression was fearful, as if her son had done something terrible.

Grandma, who didn’t say anything, looked horrified.

His eyes widening in distress, Jagan rose to his feet. But Papa, wasting no time, placed his hand firmly on Jagan’s shoulder and asked him to stay seated.

“What are you doing?” Grandma said. “The boy is not used to sitting here. He’ll sit on the floormat and eat — or he’ll eat with his father. You’re making him uncomfortable.”

“Are you sure he’s the one who feels uncomfortable?” Papa said calmly.

Stunned silence. Ravi, who didn’t know where to look, wished he could be somewhere else. He liked being around his father, but now, surely for the first time in his life, he wanted to get away from him. Why was he making a scene? Ravi had never heard him talk harshly to Grandma, who had spent several difficult years taking care of Grandpa.

Grandma, though no doubt aghast and hurt by the way her son-in-law had spoken, managed to keep her composure. “If that’s the way you feel, we’ll let you serve yourselves,” she said stiffly. “You don’t need us here.”

Amma, who had by now come out of Grandpa’s room, briskly took over before Papa could say anything more. Taking the jug of water from Grandma’s hands, she gently told her to go to her husband’s room. And she instructed Jagan’s mother to leave the dishes on the table, adding that she’d call her if she needed any help.

Papa, his face pensive, was already serving rice on their plates. Ravi lost his appetite, but he was trapped. Jagan, who looked as if he was about to burst into tears, stood up again, surprising everyone. “I have to go… Father is waiting,” he mumbled, and left quickly.

Radha, who’d been watching quietly, said, “Jagan… wait.” But he was already gone. For a moment, it looked as if she’d also get up and walk away. Wisely, she remained at the table, as did Ravi, although what followed was the most excruciating meal of their lives.

Thankfully, the awkwardness didn’t last beyond a couple of days — and when Jagan was back at the house, mainly to do chores, he became their playmate again. But while playing cricket with them wasn’t a problem, Jagan said that his father wanted him to come home for lunch. “He doesn’t want to eat alone,” Jagan said, eager to offer an explanation. “If my mother is not there to serve the food, I have to do it.”

Papa didn’t press the issue, and Ravi was relieved because he knew the customs of this tradition-bound household would not change anytime soon. Domestic workers ate separately, and never at the table. Sitting on the floormat, they used the plates and glasses reserved for them.

Radha, though, wasn’t going to keep quiet. Choosing her moment carefully, she brought it up in the presence of Ravi and their parents. The family was seated on the front porch, drinking coconut water as they watched the sun sink with a resplendent orange-red display that seemed like — at the end of another scorching day — a soothing, consolatory farewell.

“Why is this place still stuck in the past?” Radha said suddenly, and Ravi had no idea what she was talking about. “Calling it ‘custom’ or ‘tradition’ is such a poor excuse.”

“What’s this about, Radha?” Papa said, looking up from the magazine in his lap.

“You know what it’s about!” Turning to Amma accusingly, she added, “Why can’t Jagan sit with us? So backward. Is that why Jagan’s family changed their surname —?”

“Shh, watch your tongue, Radha,” Amma said. “That’s not the way to —”

Too late. Grandma, they realized with a jolt, was no longer in Grandpa’s room. He must have fallen asleep. Rushing out through the open door — she’d been within earshot — she said, “So young, but so brazen! Radha, do you know what Jagan’s father does these days?”

Radha, stupefied, mumbled an apology.

“Nothing. He can’t keep a job because he drinks too much. Bounces around. Yes, he changed their surname — but you can’t hide from your history, your lineage. Who do you think puts food on their table now? Jagan’s mother. And, yes, that’s because we employ her. Keep that in mind, young lady, before you give high-minded lectures!”

Amma, moving swiftly towards her mother, held her by the shoulder and whispered conciliatory words as she took her inside.

Change, however, can come swiftly. Much to Ravi’s astonishment, one day the following week, Jagan joined them at the table for lunch. And it went smoothly. How did that happen? The adults had apparently discussed it, and while Ravi wasn’t present, he heard that they’d come to an agreement. According to Radha, Papa and Amma argued that times were changing, even in this small town. And Amma pointed out to her parents that Jagan was her children’s playmate, not a domestic worker. It wouldn’t be right to treat him like a pariah.

The family’s annual visit ended that week, but they had one more summer at the house.

That last summer, Papa was busy with work, keeping him away from the house more than usual. They played cricket only when he was available, but the youngsters still managed to spend a lot of time outdoors, often going to the beach close by. After a few days, Ravi realized with disappointment that Radha preferred spending time with Jagan. Although Jagan tried to remain neutral at first, it soon became clear that he was drawn to her just as strongly.

They went on walks without telling him, and he was filled with an envy that scorched like the afternoon sun on his skin. Ravi was tempted to tell Amma about what he thought of as their illegal escapades. He didn’t. But one morning, when the sky looked unblemished and there was no sign of the eagerly awaited rain, Ravi followed them at a distance.

Unsurprisingly, they headed towards the beach. Sitting on a wind-sculpted rock at the edge of the sandy stretch, where a salty breeze played with their hair, they watched the ever-undulating, cerulean sea. A few gulls squawked and dived, but they were too far to pose a threat with their droppings. The inverted bowl of the sky was as blue as the shimmering water below.

What were they talking about?

At least, Ravi was relieved to note, they were not holding hands. And then, without a warning, they kissed. It was neither long nor deep, but shockingly, their lips touched — and though Jagan and Radha were not locked in an embrace, they held each other when they kissed.

Ravi quickly turned around and moved away before they could see him. Walking fast, he slipped into the house without anybody noticing him and went up to the room he shared with his sister. Amma was in Grandpa’s room downstairs, while Grandma and Jagan’s mother were in the kitchen. Papa, as far as Ravi could tell, wasn’t back from his overnight trip.

Stretching out on his narrow bed, Ravi reached for the small pile of comic books next to it. He opened one and tried to read, but all he could see on the page were cartoon drawings of Radha and Jagan. They were kissing passionately, with their eyes closed, and “xxx” appeared in the word bubble hovering above their heads.

Putting the comic book aside, he wondered if anybody else had seen them. This wasn’t a busy time for the beach. Visitors showed up in the evening, only after the sunlight dimmed and the temperature dropped, but he did see some people milling about, mostly fishermen repairing their nets or tending to their boats. He got whiffs of a fishy smell, which meant that a few fisherwomen, perhaps sitting not far from them, had spread their produce on the sand to dry.

It took about half an hour for Radha to return to the house, judging by the cracked clock on the wall. To Ravi, who picked up his comic book when he heard her, it felt like an hour. She was carrying flame-colored gulmohur flowers, which she tossed on the dresser next to her bed. They didn’t grow on the property, so where did she find them? Did Jagan…?

“So, nosy boy, what have you been up to?” she said, turning towards him, hands on her hips. “Done with your snooping?”

“What… what do you mean?” Ravi asked, sitting up abruptly, as if he’d been prodded in the back with a cricket bat.

“Don’t give me that innocent look, smarty! You think I’m stupid? I know that you followed us to the beach.”

“Well, you should be careful. You’ll get into trouble. Not a good idea to kiss a pariah in this place… especially so openly.”

With a sharp intake of her breath, Radha stepped forward and swung her right hand, striking his left cheek. The shock, more than the sting, brought tears to his eyes.

“Watch your filthy mouth, mister,” she said, still breathing heavily. “You think you’re so damn superior? Don’t turn into a lowlife, for your sake and our sake.”

Then, without another word, she spun around and left the room.

He wasn’t the only one who got slapped that day, Ravi found out later in the afternoon. Jagan’s father, after hearing from somebody that his son had kissed Radha on the beach, came over right away. He didn’t seem agitated when he arrived, but when Jagan emerged from the house, his anger flared. Berating Jagan for bringing shame, he slapped him hard in the courtyard and said that he should return home immediately. Years later, when Ravi heard that Jagan’s father had died, he wondered if the prejudice he’d faced in his younger days had embittered him. Curiously, though he’d changed his surname, he chose not to leave his hometown.

After that incident, nobody saw Jagan or his father again at the ancestral house. And none of them knew then that this would be the family’s last summer there. Grandpa died several weeks later. Grandma came to live with Ravi’s family, and the house was sold the same year.

Ravi and Jagan, though, did meet again in the same town. By then, having earned a computer science degree, Ravi was working at an IT company in a city where his parents also lived. Grandma was deceased. Radha, meanwhile, had moved abroad to pursue graduate studies.

It was a classmate’s wedding that brought Ravi to a town further up the East Coast. Making time for a side trip to the place where his grandparents had lived, he hired a cab for a good part of the day. Much had changed, and not just in the town’s commercial section. Ravi felt he’d have been lost without his smartphone and, of course, the driver. Frenetic growth near the beach, with new money pouring in like concrete for the houses that sprang up along the strip, had made his grandparents’ old neighborhood unrecognizable. The property was now occupied by two smaller homes, and they both appeared to be well-maintained if ordinary rental units.

Ravi had little information about Jagan, and what he’d heard was conflicting. He had a decent job and was doing well; no, he got laid off and was struggling. He wasn’t married; yes, he was married and a father. The only undisputed part was that, while Jagan’s father had died, his mother still lived in the town, perhaps in the same area.

The only way for Ravi to find out more was to go where they used to live. Getting back in the cab after taking a couple of pictures, he told his driver to drive north. The road, though narrow, was well paved and it didn’t take long for them to reach the settlement at the edge of a sugarcane field. But what used to be a cluster of mostly mud dwellings with thatched roofs was now a colony of modest brick houses with sloping, red-tiled roofs. Jagan’s grandfather, who used to work for a sugarcane cultivator, had brought his family to this area.

Disoriented by the changes, Ravi didn’t know where to go. He’d come here on his bicycle just once before, years ago. Telling the driver to wait, he got out of the cab and walked towards the houses. In the distance, the green sea of the sugarcane field, laid out in neat plots, signaled continuity and prosperity. Near the first row of homes, he approached a middle-aged man who was about to get on his scooter. Ravi greeted him.

Yes, Jagan still lived here, the man said, pointing at an identical-looking house two doors down. His mother should be in even if he wasn’t, he added before starting his scooter.

Ravi rang the bell a little nervously, wondering if Jagan’s mother would recognize him. She didn’t. Grayer, and thinner than he remembered, she looked at him in puzzlement. Rather than seeing him as a stranger, she seemed to be trying to make a connection. He looked familiar, apparently, but she waited for Ravi to introduce himself.

“Of course, of course!” she cried, her face lighting up like an incandescent bulb. “I should have known, though it’s been so long and you’ve changed. A handsome young man. Please come in. How are you doing? I’ll call Jagan . . . he has also changed.”

Apologizing for coming unannounced, Ravi said he had neglected to plan his trip properly, not knowing if he’d have enough time to hire a cab and come here alone.

Assuring him that she was delighted to see him — in fact, his visit was well timed — Jagan’s mother asked him to sit in the most comfortable chair, a reclining armchair, in the small living room. Her son had a job at the sugar factory, but he was off that day, a Sunday. A short while ago, he went to the bazaar to buy a few household items. Noting that Jagan would be happy to see him, she said that she’d call him soon after getting a glass of water for Ravi.

But even before she returned from the kitchen, Jagan barged in through the unlocked front door with a big smile on his face. Tall and strapping, he looked older than his age. Clad in blue jeans and a striped polo shirt with the top button undone, and sporting a close-cropped beard, he had thick dark hair that almost touched his shoulders. Putting his helmet down, he went up to Ravi, who rose from his chair before they embraced and greeted each other.

“Wow!” Ravi said, stepping back. “You look good, Jagan, but I might not have recognized you on the street. You’ve changed so much.”

“That’s funny,” Jagan said. “I was going to say the same thing. You look great. I couldn’t believe it when our neighbor said you were here. I bumped into him in the bazaar. He was mistaken, I thought, but he insisted that a man named Ravi was looking for me. I don’t know any other Ravi. What a pleasant surprise! We have a lot to talk about.”

“Indeed. How about going to Main Road? In the cab, I mean. It’ll be nice to look around, but also, while we chat over a cup of coffee, the driver will take a break. He can eat somewhere.”

“You’re joking, right? Forgive me for saying this, but please don’t insult —”

“What… of course not! Sorry if I caused offense, Jagan. This is an unexpected, unannounced visit… and I don’t want to impose on your mother.”

“Believe me, Ravi, it’s no imposition. My mother will be upset if you don’t eat here. We can go to Main Road afterwards, and the beach as well if you haven’t been there yet. Lunch will be ready soon, I’m sure. We can ask the driver to eat with us.”

“Yes, of course, we should invite the driver,” said Jagan’s mother, who’d returned from the kitchen. “I’ve cooked… lunch is almost ready. There’s plenty of food. I don’t have to make anything extra. Please inform him.”

“I will,” Ravi said. “This is most kind —”

“No, no, don’t say that. Such a pleasure to see you after all these years. Jagan, show Ravi where we’ll be eating.”

“Sure, Amma,” Jagan said, grinning.

He took his shoes off and then led Ravi to the room adjoining the kitchen. Small like the living room, there was nothing special about the airy room with its open, barred window — except for an old but solidly made wooden table and four chairs occupying much of the space.

Ravi gaped. “This is the same —”

“Yes, it’s the same table,” Jagan said. “Same chairs, too. We got them from your grandmother. She asked us if we wanted to take anything when your family sold the house. We didn’t take anything else. We’ll be eating here.”

“Perfect,” Ravi said. “I’ll tell the driver.”

Appeared in Issue Fall '24

Nationality: USA

First Language(s): Telugu

Second Language(s):

English

Das Land Steiermark

Listen to Murali Kamma reading "Friend of Their Youth":

Supported by:

Comments on "Friend of Their Youth"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login