Published June 27th, 2022

Review

by Zara Miller

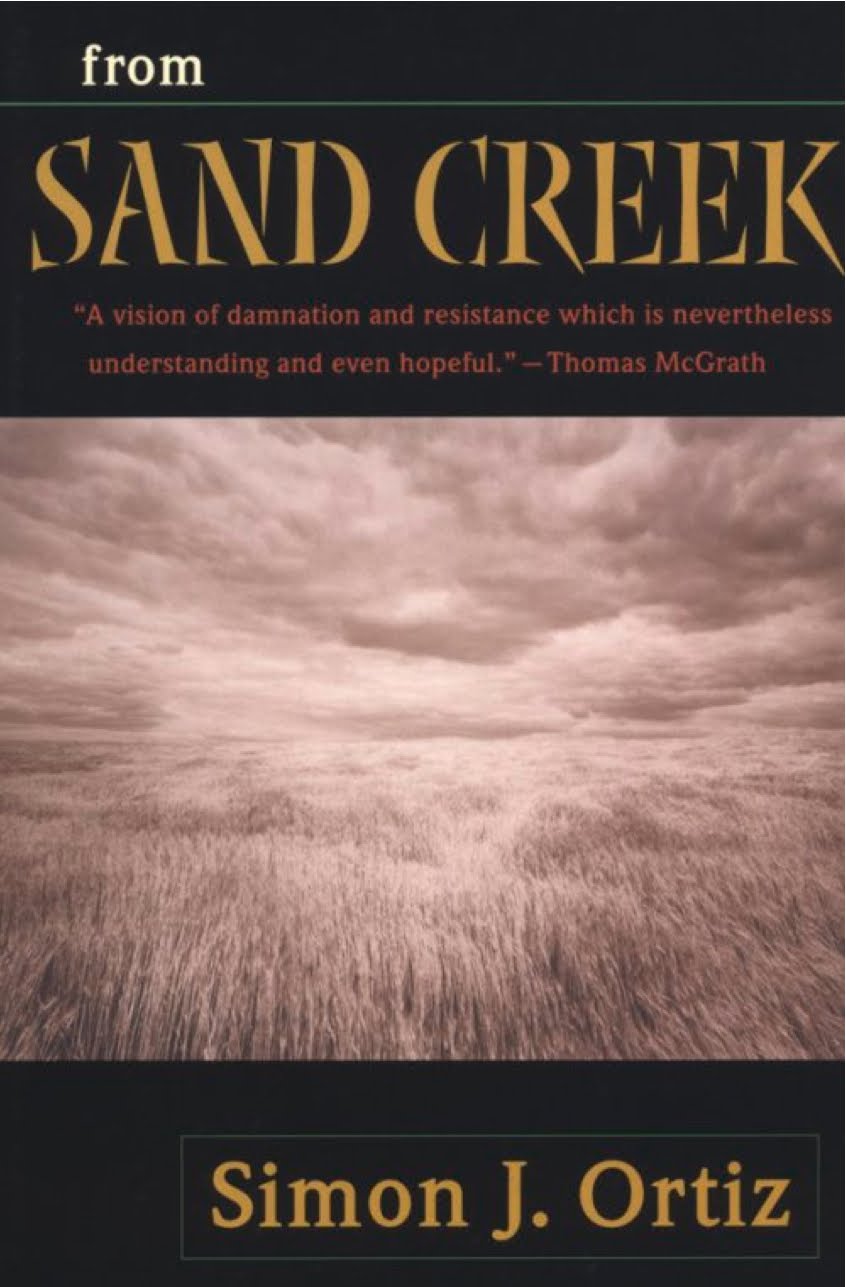

Simon J. Ortiz's crown achievement From Sand Creek: Rising In This Heart Which Is Our America (1981) is a perfect representation of the Native American Renaissance in literature. More a storyteller than a poet, Ortiz has received numerous accolades for his humanitarian and literary efforts. From Sand Creek is a masterpiece in balancing injustice with empowerment and this review takes a closer look at this timeless masterpiece. In this review, Zara meditates on the meaning of poetry, and of the poetry in From Sand Creek in particular, in connection with the recounting of national history and personal tragedy.

A tale as old as time.

Or at least some two hundred-forty-six years. What does it mean to be American?

Several ethnic groups grapple with that question, it’s been embedded in their souls, or consciously passed down by the systems too conveniently (for some) constructed to be torn down. Or perhaps, equally consciously by their families, to protect, to prevent, to let the children know which side of the river they are allowed to row on, but always crystal clear that it wouldn’t be Potomac.

There is a fine line between misery and melancholy. Shakespeare would argue that there is no way to tell a story of tragedy without giving in to high melodrama or succumbing to the depths of hopelessness. They say write what you know, but when your knowing is inherited, you are confronted with pre-recorded notions, and it is somehow crueler to have your reality confirmed than to be surprised by it.

Poetry often does that. Romanticizes reality, or perhaps it’s just the beauty of rhymes that sound romantic to our ears. Tragedy is not romantic; yet more works of poetry are set at the backdrop of a tragedy anywhere from large scales of biblical legends and ancient myths to the loss of a single life due to greed.

Historical fiction is a tough subject to tackle because a writer is fighting audiences’ pre-recorded notions and there are expectations to come to the same conclusion historians came to or get as close to it as possible. Otherwise, the writer is exposing themselves to dissatisfaction. In historical fiction, real-life history is the setup and the work of fiction is the pay-off. Challenging history means challenging prejudice. We are all a product of our time, and so is the art we make.

Hardly do we find a property that exposes what people hate the most: the truth. Truth does not jive with fiction very well. Some might say that truth is the enemy of fiction. You cannot think of poetry and allocate it to a work of non-fiction in your mind. No poet lends his voice to the molecular structure of glass.

That’s where the genius of a poet comes in. Choosing to confront the reality he lives in by lending his voice to a historical event he is exposed to but one that many do not even know of. Or choose to forget.

The eternal debate, whether it is the toiling red gentry or the Wall Street blue aristocracy that embodies the one true Americana, omits the Native American reality from the conversation altogether.

And then holding it accountable by putting it on record. Maybe even slipping in a note or two about hope. There is always hope.

“This America

has been a burden

of steel and mad

death,

but, look now,

there are flowers

and new grass

and a spring wind

rising

from Sand Creek.”

There is something else exceedingly beautiful about Ortiz’s verses. Patriotism to the land, sure, but more so the lack of self-righteousness is a rare occurrence among writers, and especially poets. It is of higher value here, when he contextualizes that people of color and his people in particular are not a single file with one voice, but a crowd of individuals with loud, differing opinions united by the strength of conviction.

He gives the best gift a writer can give — the right to individuality.

The melodrama and the melancholy of poetry often seep into the pores of a writer, giving them a sense of higher calling — setting them on a heroic journey when they and they alone can resolve the injustices of the world. Only they have the right answer, and the magic of the self is a secret hidden in the book.

Now please, go buy it.

Ortiz gives a much more nuanced approach, untouched by the digital era and the savior complex of a young generation. It does not propel powerlessness and helplessness by attacking what is approachable and easy to dismantle — an incorrect opinion or a bad joke at a comedy show.

It simply is. Simply existing has become such a foreign concept, such a boring, unimaginable stoic action that reading his poems feels like entering a state of simply being.

And where there is silence, there is room for thought.

Sand Creek witnessed a massacre in 1864, largely omitted from history books, forgotten by the intelligentsia. Whether we would want to play a devil’s advocate and accredit the lack thereof record to a focus on a much larger loss of life at Gettysburg, we cannot override the importance of a tragedy because of a scalier tragedy. The bigger picture does not apply here.

“In 1969

XXXX Coloradoans

were killed in Vietnam.

In 1978

XXXX Coloradoans

Were killed on the highways.

In 1864,

There were no Indians killed.

Remember My Lai.

In fifty years

Nobody knew

What happened.

It wasn’t only the Senators.

Remember Sand Creek.”

The call to collective responsibility is vital in Ortiz’s book, transcends the pages. No, not a straight white guilt approach — a complex human approach. The black and white of categorizing which life matters. Geneva conventions might state, black and white, that every human life is of equal value, President Obama might sign more than 71,000 acres into federal trust status for six Nevada tribes.

All black and white can do, is offer symbolic comfort and slim to nil chances of justice.

And unveil all the iron-taste red at Sand Creek.

“ … They should have seen

The thieves stealing

Their most precious treasure;

Their compassion; their anger.”

The collection reads like a diary. It is almost too privy for public consumption. It is a glimpse into the struggle of reconciling an inner world of a man with an outer world that does not want him there. A silent cry, a loud banging on the chest to be heard, an empathetic glimpse into a reality that feels distant both by design and by choice.

Mostly, it attacks the core issue overlooked by the short-sightedness and a short apparatus of history not going back in time deep enough. Far enough.

It was not born in the United States. Whatever “it” is. Substitute “it” for whatever evil comes to mind. There was peace and a code before Europeans landed in the Americas and brought “it”.

Instead of debating who is more American, we should be debating who is least European. The continent that loves to distance itself from the 90% of the world that was plundered and pilfered under the banners of liberation and civilization of the oppressed and uncultured. Ortiz loves the American land as much as he loves to show Europeans and those of European descent to confront the motives and the consequences still ringing throughout the Native American tribes and communities.

“The traders who dealt

In whiskey

Came

Imploring a false trust so thorough

And sincere even Black Kettle

Did not turn away;

He withered

Like a dying root,

Even winter knows no such sorrow.

Whiskey and Poisoned.”

Whiskey offers comfort until it poisons the brain to a convenient black-out at best and cancer that will keep growing until we perish, at worst. It is as tragic as the fate of poetry — to be used as a conduit of tragedy for all eternity.

Nationality: Slovak

First Language(s): Slovak

Second Language(s):

Czech,

English,

Russian,

Spanish

Supported by:

Comments on "The Tragic Fate of Poetry — A Review of "From Sand Creek" by Simon J. Ortiz"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login