Published December 21st, 2021

Review

by Sam Dapanas

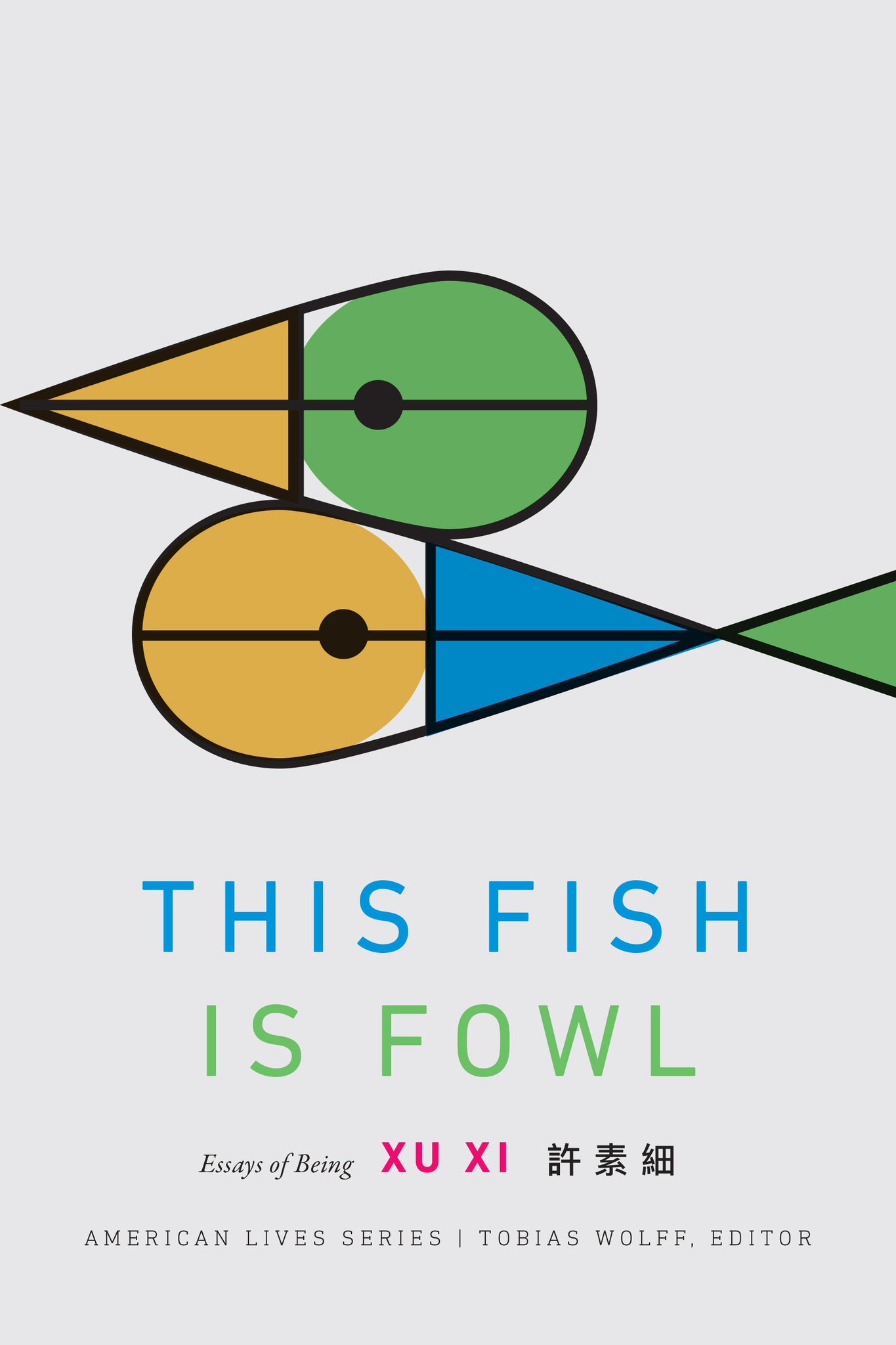

Identity is not fixed. Sometimes, it can be fluid or even unfinished, as if it is never meant to be finished at all. In her last collection of essays, Hong Kong writer Xu Xi masterfully navigates through the terrain of identity, being, and home, while questioning what it means to belong or just to be.

Where is homeland or citizenship or nationhood when, in the eyes of the world around you, you don’t have one or are not supposed to? For award-winning fictionist and essayist Xu Xi — who self-describes as a “Chinese Indonesian, former Indonesian citizen, native of Hong Kong, domiciled in the world” — mincing words is not an option in trying to address these important questions. Living in the United States and dealing with Americans but unable to name the second senator of New York State, Xi writes:

I recall one Cincinnati acquaintance loudly protesting the lack of world historical knowledge among the young, he being middle aged and belatedly recognizing that his time spent in such knowledge acquisition now impressed no one save himself; his idea of world history began with the Roman Empire and ended in England, as all other history was presumably negligible. But about Cincinnati, Mark Twain did say he would stop there only when the world ended because everything arrived there twenty years too late, including, no doubt, its inhabitants.

Comprising of 30 stand-alone essays grouped in four sections each titled after a representative essay — “On Being,” “Mum and Me,” “Wo/Man Roars,” and “Origins” — some of which were previously published in reputed nonfiction outlets like Fourth Genre, The Iowa Review, Hotel Amerika, Wasafiri, Ploughshares, and Asian American Literary Review, this collection of essays — or more appropriately, memoirs in essays — is, as the subtitle suggests, about coming into terms with who you are. These essays grapple with the many contradictions we confront concerning belongingness as if belongingness were but a rigid, dualistic concept between black and white, between the state of having-to-be-in and not-being-at-all. In the essay “Why I Stopped Being Chinese,” Xi challenges those who are sociologically labeled as Third Culture Kids: “They need reflect far, far less on which skin colors, which languages, which countries demand or deserve allegiance. A passport is a mere carrying card for border crossings, and the idea is to fit in everywhere and nowhere as awesomely possible.”

The essays make us think of territories, of how truly divided we are in a community with imagined homogeneity and real borders. Regardless of physical location, skin color, or spoken tongues, these are the paradoxes between the grand loyalties we flaunt and the subtle betrayals we conceal. For instance, as if asking from a nationalist, essentialist point of view: who is more Chinese, which one is more a republic than the other? Such divisiveness fuels geopolitical tensions between those living in the homeland versus those in diaspora. “All my life I’ve encountered ethnic Chinese who deny me the right to be Chinese because of my language, demeanor, blood,” Xi writes.

I find this collection also, in one way or another, a reflection of her own writing, a poetic exercise, a query on her own Muse, as a representative of Anglophone writings in Hong Kong. As if in retrospect, Xi, in her introduction to City Voices: Hong Kong Writing in English, 1945 to the Present (Hong Kong University Press, 2003) which she co-edited with Mike Ingham, writes:

We were all accidents that happened upon this former British colony on whom the Muse, or some lesser goddess, foisted her imperative, in English to boot, and made us what we are. Yet as we hover at the top of the twenty-first century, I look back at my own writings, and those of others, that emerged out of what was once an extremely narrow sphere, and realize that a body of work now exists, which, while hardly a cornucopia, represents the beginnings of adult, as opposed to adolescent, squawking.

From fruit flies, the IRS, and American proxy wars all over the world, to Emily Dickinson, Xi’s colonial education in British Hong Kong, the hierarchy of being Chinese and being in a republic (Hong Kong versus Taiwan versus mainland China), the American unaware ignorance of world history and, in turn, Xi’s apathy towards American history, Xi’s This Fish Is Fowl pokes fun with satirical humor but with a critical eye (“…rather un-American I might add, not succumbing to a linear narrative”), and is symptomatic of any writer who writes English as a second or foreign language. For example, she code-mixes with Chinese on occasion and employs wordplay, i.e. “this here,” a transliteration from Cantonese. Consider her stance on being a green card-holding ‘legal alien’ because she is married to an American citizen:

I swallowed the idea of being American as if allegiance and residence and good standing with the IRS would make me American. It wasn’t as simple as taking patriotic duty seriously because in some circumstances that will get you killed, which seems downright unpatriotic: to be all you can be one day and blown up in Iraq the next because some historical figure playing presidential musical chairs decides to declare war.

Xi also turns philosophical in challenging the gray areas between Being and Becoming. “Is home ‘home’ only by default, almost defunct?” are among the many questions, almost rhetorical, that propel the collection forward. In “Citizenship” and “Mum and Me,” as in most essays here, she breaks the fourth wall as a nonfiction technique, possibly to create a more authorial tone while at the same time maintaining an authentic nonfiction persona that questions the reliability of her own memories: “But it is only now, essaying on citizenship, that this refusal to do so puzzles me into reflection,” “Restart. Revise … Replay. Recall,” and “My appeal against that denial was successful, otherwise I might not be penning this essay today.” This collection, in my view, also acts as a dispatch from an Asian travelogue — her Indonesian passport, her mother’s ID in a Hong Kong school, a coin in Hong Kong dollar, and photos from the Umbrella Movement. Xi not only cements herself as a household name in literature classes on contemporary Anglophone writings in Asia as named by Jette G Hansen Edwards in The Politics of English in Hong Kong (Routledge, 2019), she also shows us that this is exactly the kind of collection only a citizen of the world could write.

Nationality: Filipinx

First Language(s): Cebuano Binisaya

Second Language(s):

English, Tagalog-based Filipino

Supported by:

Comments on "The Loyalties We Flaunt, The Betrayals We Conceal — A Review of "This Fish Is Fowl" by Xu Xi"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login