Published April 7th, 2020

Review

by Carolina Varga

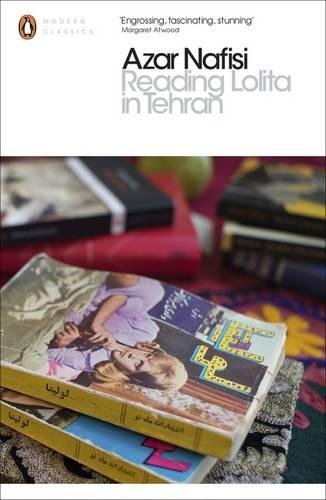

Reading Lolita in Tehran is a memoir by Azar Nafisi, recounting her life in Iran during the revolution in 1978-1981 until her emigration in 1997. ESL writer Nafisi was born in Iran but continued her education abroad from the age of 13. She returned to Iran in 1979, where she taught literature at Tehran University.

In the opening pages of her memoir, Nafisi writes that if she were to choose a work of fiction that most resonated with her life in Iran, she would choose Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. At first, this statement sounds improbable. What correlation could a middle-aged man's exploitation of a 12-year-old girl (the premise in Lolita) have in common with Nafisi's life in Iran? In the pages of her memoir, Nafisi weaves intricate analysis of works of literature through the events of her life and reminds us that “what we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth.” Lolita particularly resonated with Nafisi's sense of exile in her own country, and the feeling of becoming involuntarily complicit with the regime's crimes against her.

By the time Nafisi returned to Iran, the new political regime had penetrated all aspects of day-to-day life, including teaching, which became subservient to politics. The regime wanted to “purify the educational system” and create a new curriculum that reflected its ideology. Faculty and students resisted this by organising demonstrations and sit-ins, which often turned violent. Ordinary citizens were put on trial or disappeared; bulletins noted that they had been jailed, or that they had been executed.

In this atmosphere, for Nafisi, books became a sanctuary, a vessel for imagination and a form of sustenance containing kernels of truth in the otherwise unrecognisable landscape of her life. Literature became not a luxury, but a necessity and the act of reading non-prescribed literature became a quiet act of defiance.

The memoir is told through the prism of some of the books which Nafisi taught to her students: Lolita, The Great Gatsby and the works of Henry James and Jane Austen. As a reader, I had the feeling of being a student in Nafisi’s classroom, sitting in the lecture hall, listening to her speak. However, I also had the feeling that it was not an ordinary classroom.

One aspect which struck me was that professors feared their students. Some members of the student body belonged to political groups and the more fanatical students reported their professors to authorities for teaching material which they considered to be “morally harmful.” One student took offence to The Great Gatsby. Incredibly, this led to a mock classroom trial, with the accused being… the book! The book’s crime, according to this student, was that “it was representative of things American, and America was poison for us.”

Another point of contention were the works of Henry James. That is no surprise, given that the female protagonists of James’ novels “defy the conventions of their time [and] refuse to be dictated to”, displaying a valiant desire to “preserve a sense of personal integrity in the face of outside aggression.”

In between being expelled from one university (for refusing to wear the veil) and commencing teaching at another, Nafisi formed a secret book club comprised of seven of her female students. These women formed a camaraderie through their discussion of books, which inevitably turned to sometimes painful revelations about their own lives.

Although the book club was a source of levity and refuge for the women, outside those four walls was a life that was arbitrarily brutal, which they had to return to. Each of the women had their own way of surviving, and one was, as Nafisi puts it, to “escape inwardly” so that “the essential part of their life [went] underground.” However, after finishing the memoir, a question lingered on my mind: what if it never became safe enough for them to re-emerge?

Nafisi observes that “Lolita belongs to a category of victims who have no defence and are never given a chance to articulate their own story. As such, she becomes a double victim: not only her life but also her life story is taken from her.” In writing this memoir, Nafisi and the people whose stories she shares in it, can perhaps escape that “second crime.”

Nationality: Hungarian

First Language(s): Hungarian

Second Language(s):

English,

French,

Russian

Supported by:

Comments on ""Reading Lolita in Tehran" by Azar Nafisi — A Review"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login