Published March 13th, 2023

Review

by Tabish Nawaz

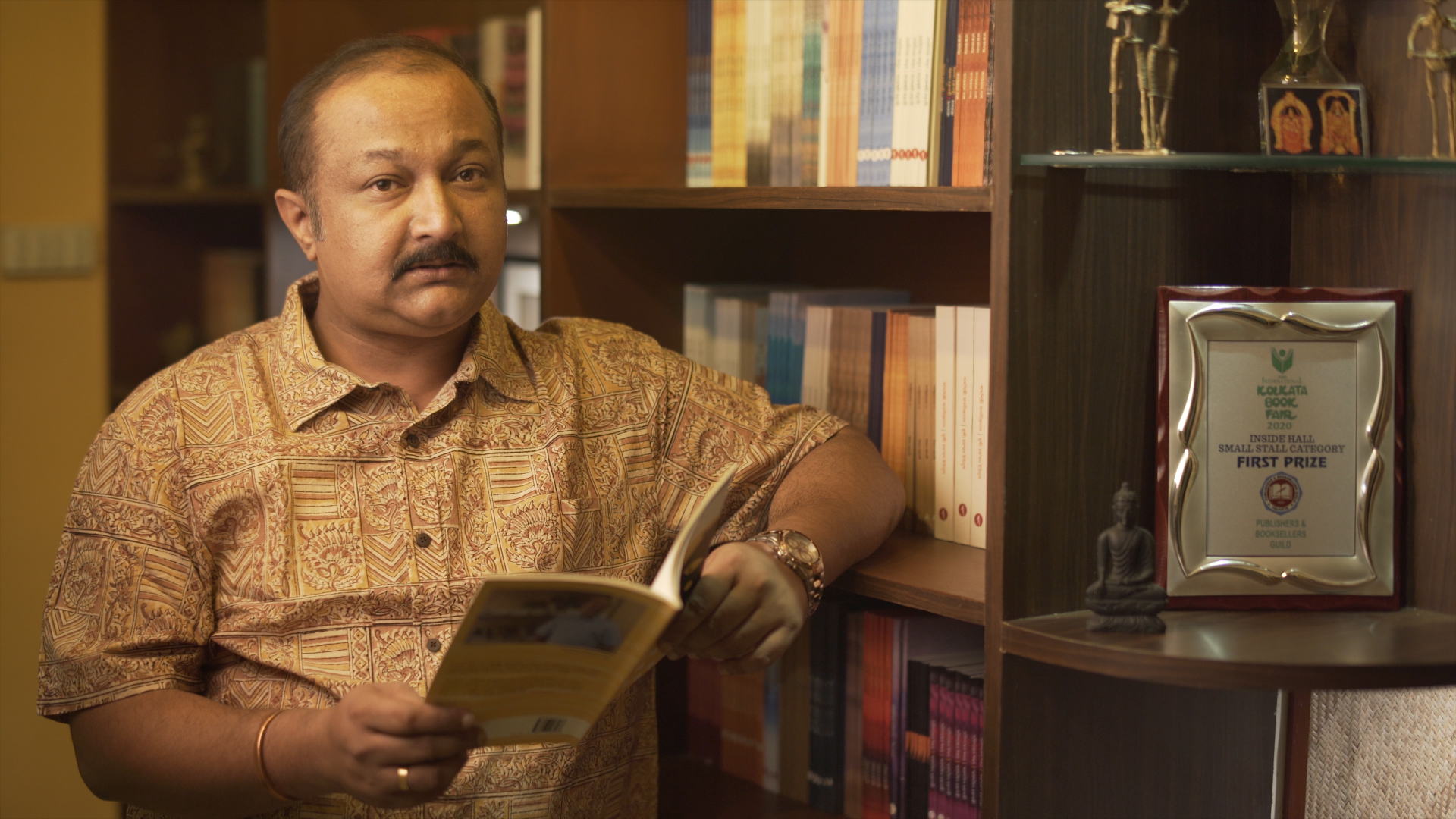

My interest lies in locating the elusive self in the medium of life it is immersed in, observe its many shades as it splits along experiences, like a ray of light passing through a prism, fragments into a spectrum of colors. To this end, I look up to poetry as a metaphysical document that can capture the vibrations of the self in language and shed some light on its mystery. I have been exploring the self through poetry for quite some time. And this quest has drawn me to mystical poems from Bhakti, Kabbalah, Zen and Sufi traditions. In Western poetic tradition, Transcendentalism of Walt Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau served as an inspiration until I found a haven in the poems of Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa and his heteronyms. The search in the Indian context resonated when I came across the poems of Kiriti Sengupta.

I have been reading Sengupta's poems since I began exploring contemporary English poetry in India. Of the many Indian poets, I am reading, I found his poetry to have a penchant for giving voice to everyday ordinariness in English language. He articulates common mute experiences which have a unique Indian flavor, possessing diverse plebeian tenderness, in a minimalist fashion. I love how Sengupta’s poems make rituals of our daily acts, casting their seemingly ordinary aspects into something that become pregnant with cosmic meanings. In his latest collection Water Has Many Colors (November 2022, Hawakal), Sengupta dwells on the multiplicity of the self, capturing it in our daily acts, big and small, in events ordinary and cataclysmic. When I began reading, I was reminded of the poetry of Walt Whitman.

“I am large, I contain multitudes,” wrote Whitman in his poem “Song of Myself” determined to identify his own self in everyone and everything and locate the universe within him. I felt a similar multiplicity of existence as I began to read these poems.

The collection begins with the poem “Spectrum” where Sengupta opens the dialogue on diversity existing in a form:

Water has many colors,

smudging pebbles

along its path.

Water, here perhaps, is a metaphor for life or poetry itself. In the poem, I not only perceive water’s many shades but also its flow as it keeps “smudging pebbles.” As though wateris poetry creating a spectrum of meanings around words, or life spawning a spectrum of beings within a self. In a sense, Sengupta celebrates life through poetry and if one is able to identify the spectrum within or around oneself, one has lived a life worthy of poetry.

While celebrating the many selves, Sengupta in Santiniketanalludes how, hidden between the persona and the appearances, the self dwells.

Aesthetes preach Tagore.

Officials display replica of

the Nobel Prize.

Here I again feel a parallel between the self and poetry. Poetry is at first a concealing art, revealing only to the ones it chooses. No amount of effort is going to bring about the revelation. Similarly, the self becomes evident only to those who seek it, while appearance ensures that only the seekers are able to see through it. However, in “Bucolic Bengal 7,” the poet goes no further and celebrates the appearances:

Her gaze is fixed.

Mien limns the reality.

By providing a series of snapshots of an everyday life in “Bucolic Bengal,” Sengupta crafts the reality as a world of images, even if it is only surface, it is enough. One encounters absurdism of reality, quite like Albert Camus’ absurdism of life. Here too, I realize that though the reality is of deceptive appearance, and even when its nature is understood, its celebration is the only human response, just as Camus recommends embracing life with happiness despite its meaninglessness and absurdism in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.”

Fancies fathom no ceiling.

Can iris assess the zenith?

Kites are born of chimeras.

(“Bucolic Bengal 4”)

As I delve into the collection, I find poems celebrating everyday mundaneness, and it is hard not to believe that I am not in Whitman’s universe. Sengupta has a keen eye for recording the wonders of daily life. However, I feel that it is not just the wonder that moves him, but there seems a conviction within him for giving voice to his, otherwise mute, daily acquaintances.

Climbing the stairs,

he calls my mother.

His voice reverberates.

Laundryman is at the door.

In “Housekeeper,” we witness a familiar image from our daily life, however, on reading it feels that there is something stirring beneath the surface, as if a guilt or a remnant of most hidden of our activities, which even one encounters, one prefers not to talk about them. We hear more mute voices in the following poems:

Strays recognize the regulars.

Road-side tea stalls house a convoy of canines.

They chump or chew as walk-ins stop by.

Owner of the kiosk discreetly suggests

the stuff the mutts cherish.

(“Line of Control”)

And

The buzzer chimes.

And a thumping sound

assures me of news-

paper

From my balcony,

I spot the newsie

with his bicycle.

Moisture

graces his features.

(“Paperboy”)

With the last line, an image of daily hardworking folks is reaffirmed, and one can imagine that faceless face on reading the poem and it persists. It is hard to put any identity to that face, it reveals itself in its commonness.

-teji-sethi.jpg)

The poems with its many images of ordinary folks carry forward Whitman’s legacy. As much they cheer up the working class, they equally rile up the kings and gods. As in “Boris Johnson in Isolation,” we see an image of a powerful nation’s premier being forced into isolation by a deadly virus. The poem also alludes to the democratizing instinct of nature’s deadly forces, and how easily we are sublimated to it, no matter whether a king or a slave.

With newsflashes, we’re alerted—

policy warrants seclusion.

Kerfuffles over the microbe

leave us baffled: isn’t there

any limit to its influence?

The poem “When a Woman Conquers God” glaringly shows that when an ordinary human being transcends divinity, they can make God look limited.

Bridal in rural layouts

are reminded of Behula.

Her commitment and how hard-

ship failed to mute her ardor.

Onerous it was to fetch your

favor. Behula reifies devotion.

Legend stresses a laundress

ushered Behula to heaven

to revive her late spouse.

Similar celebration of ordinary folks is noted in relation to the figures worshipped in Indian traditions. As in “Urvashi—Beyond Her Siren Avatar,” we observe that without belittling the Gods or prominent characters, a center space is feasible for the characters that belong to the margins.

The Mahabharata does not

ratify your fondness for Arjuna.

It must be severe when he

declined your plea.

Worthy was your forethought

as you imprecated him.

In his last year of living incog,

Arjuna turned into Brihannala.

Similarly, in “Game,” I observe an equilibrium between the goddess and the worshippers, as if honoring each other’s space.

Women arrive

with a pot of vermillion

as the goddess departs.

Another recurrent theme in the collection is of homesickness. However, here the homesickness is not merely a nostalgia of a lost home, but a feeling of having lost our space in eternity, pivoted on an individualism borne out of an alienation from our spiritual self and disconnect from our natural being. This theme of homesickness reminds me of the prose and poetry of Herman Hesse. In the poem “Hibiscus,” it is apparent that the two forces—divine and nature have been introduced as divine father and mother nature.

The vow ceased with his death.

The world expanded.

They never missed a chance

to cram her to misery.

Can we be of help?

In the line “The world expanded,” Sengupta alludes that how with the death of divine father, the individual self as ego expanded, leading much of the civilization into the western idea of enlightenment, resulting in depredation of mother nature. In the end, the poet asks if we can help. And, here we see the power of poetry in making up for the loss and perhaps overturning the trajectory of civilization, and achieving the unity between the divine spiritual self and the instinctive natural being within an individual. Without this unity, one feels a void at the center of ones being, as reflected in “Multiplex”—

Bedbugs bite no more.

Popcorn and beverages

offer recurrent intervals.

Here we witness a comparison of two agents of intervals in a cinema theater—the former consumed us and the latter we are consuming. The juxtaposed images of consumerism and sanitized space again emphasize that we have created a self that worships itself through the rituals of consumerism and nature has been exiled to the periphery of our existence, only to provide consumable for our self-serving.

By shunning of nature and exiling of divine humanity has been atomized and suspended in its many individual sacs as though sitting in a multiplex, unaware and unobservant of others. As “Coterie,” makes evident:

Air-conditioning helps appraise accommodation. Windowpanes don’t open to the sky. Owners enhance décor with filament lights. A flame tree stands alone beside the gateway. Old leaves cover the passage. Wood is abolished to expand highways. The flamboyant tree dies from Roman vitriol.

The poems in Water Has Many Colors are faithful to the title, each bearing the multiple shades of human existence, but it is to the deftness of the poet that credit must be made that the multiplicity is revealed in its luminosity. The craft is minimalistic, and the illustrations enrich the depth and imagination of the readers. The poems have an urgency and also to an extent a wry humor that persists for a while. Although the verses are well-crafted, there is something that hangs loosely between the lines. And, that provides energy to these poems, making them persistent and seminal.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Hindi

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by:

Comments on "Minimalist yet Luminous Multiplicity — A Review of "Water Has Many Colors" by Kiriti Sengupta"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login