Published August 12th, 2024

Review

by Richard M. Cho

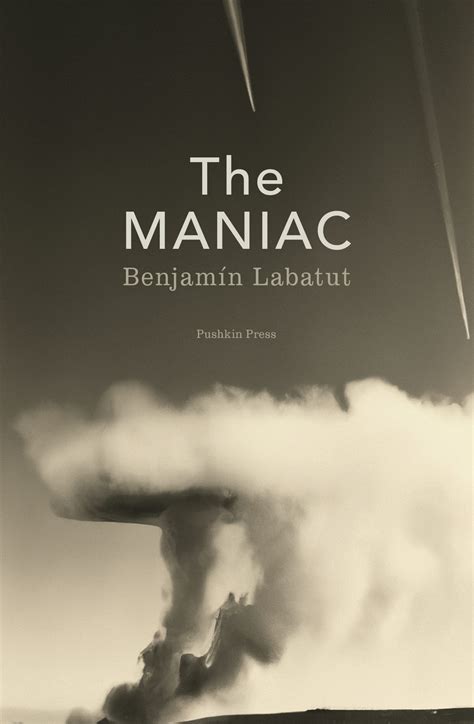

For centuries, faith and science have been adversaries. Churches long fought to debunk any scientific advances they saw as contradicting the Holy Scripture, such as Galileo’s Copernican Heliocentrism and Darwin’s natural selection theories. Even today, we can see billboards discrediting evolution, with an emphatic “X” over the step-by-step metamorphosis from an ape to erect man. Yet, in 21st century Western liberal democracies, science seems to have achieved relative dominance over faith. The argument is that science is rational and evidence-based whereas faith is “baseless” and even dangerous. But, if faith indeed endangers civilization, are we safe with science? The Chilean writer Benjamin Labatut's electrifying new novel The Maniac (2023) hints that the real danger, the kind that can wipe out humanity, has been with science, with our relentless quest for scientific progress.

Labatut labels his novels “non-fiction fiction.” During an interview, Labatut professed that “anything that comes out of a writer is fiction,” and that fictional qualities “give reality a human shape.” His usual subjects are scientists with super-human intelligence (such as Werner Heisenberger and Erwin Schrodinger, and for this new novel, the forgotten genius of the 20th century, Johnny von Neumann), whose larger-than-life accomplishments must be molded into “a human shape” for readers to relate. Expanding on themes that Labatut explored in his previous novel, When We Cease to Understand the World (2020), The Maniac asks: What might be the unforeseen consequences of many scientific ideas that were woven by scientists not so rational in their ambitions? If his previous novel prefigures the era of nuclear threats, then the bomb goes off in The Maniac.

The Maniac, Labatut’s first book written originally in English, is composed of three sections: 1) the life of Paul Ehrenfest, an early 20th century physicist whose disillusionment in science and mathematics cut short his career and life; 2) the life of the Hungarian polymath Johnny von Neumann; and 3) the Go match between Lee Sedol and AlphaGo, an AI program.

Part one, titled “Paul (Ehrenfest) or The Discovery of the Irrational,” begins with the tragic story of an eminent physicist who killed his young, disabled son before committing suicide at the age of 53. Unlike many towering geniuses at the time, he was a “man not without virtue,” and other scientists nicknamed him the “Conscience of Physics.” Ehrenfest mediated between the two major players in physics of the era, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, during the fateful Solvay Conference of 1927. After Bohr and Heisenberg’s new revolutionary principles of uncertainty in physics, Ehrenfest “could not shake the feeling that a fundamental line had been crossed, that a demon, or perhaps a genie, had incubated in the soul of physics, one that neither he nor any succeeding generation would be able to put back in the lamp.” Ehrenfest feared these scientists had discovered “something that negates the natural order entirely.” His trust in science dashed, Ehrenfest suffered from fatal anxiety. The section ends with the black and white photograph of Einstein doting on Ehrenfest’s son, while Ehrenfest looks on with pride in the background.

With the title “John (von Neumann) or The Mad Dreams of Reason,” part two opens with a single sentence that occupies an entire page: “He was the smartest human being of the 20th century.” Von Neumann’s life is presented by his family members, fellow scientists, and even by his enemies; each taking turns to share their subjective analysis. This collage narrative is effectively rendered with distinction: Some narrate with equanimity, some rave with admiration verging on worship, and others rant with fulmination. Each narrator has a different speech pattern, diction, and tone. Not surprisingly, Neumann’s wife and daughter focus on their fractious relationships with the genius.

Born János Lajos Neumann, von Neumann had “the mind that had birthed the modern computer, laid down the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, written the equations for the implosion of the atomic bomb, fathered the Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, heralded the arrival of digital life, self-reproducing machines, artificial intelligence, and the technological singularity,” just to name a few of his achievements. He was of “a superior species, an evolution beyond man.” He died in 1953, but he left his fingerprints everywhere, from PCs to advanced weapons to ChatGPT. In fact, the reason that he is not a household name in the 21st century could be that he excelled at everything he set his mind to, revolutionized just a bit too many fields, unlike other august Princeton resident scientists whose names were mainly attached to single, grandeur achievements, like Einstein's General Theory of Relativity or Kurt Godel's Incompleteness Theorems.

The novel emphasizes, along with von Neumann’s brilliance, his moral blindness (as compared to Ehrenfest's virtue). “A sinister, machinelike intelligence that lacked the restraints that bind the rest of us,” one narrator recounts. Pertinacious in his efforts to pave new scientific ground, his raison d’être, he put aside his ethical sensibility. As an advisor to the Manhattan Project, he recommended detonating the atomic bomb exactly 600 meters above Hiroshima and Nagasaki to inflict the greatest damage possible to the land and its people. Interestingly, a chapter narrated by the celebrated American physicist Richard Feynman could be a companion piece to the movie Oppenheimer by Christopher Nolan, as it unveils the everyday customs of scientists building the first atomic bomb in Los Alamos, New Mexico. In their downtime, scientists drank punch laced with ethyl alcohol stolen from labs, and many of them were hooked by the game of Go (the best player was Oppenheimer). We learn that what compelled these scientists to endure the boredom of this nowhere town wasn't the prospect of power or wealth, fame or glory, but the “sheer thrill of the science involved.”

Von Neumann was in thrall to such a thrill. When he was introduced to the world's first digital general-purpose computer, ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), he poured his soul into creating a more advanced version that upon completion he christened MANIAC (Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator and Computer), which could mathematize and facilitate the making of a hydrogen bomb. Yet, his most prominent legacy is his contribution to automata and theories of self-evolving machines, which later became the progenitor of artificial general intelligence. “Cavemen created the gods. I see no reason why we shouldn't do the same,” von Neumann said.

Part three takes place some 60 years later. It chronicles the development of AlphaGo, an AI program created by a team led by DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis. In 2016, the best Go player in the world was Lee Sedol, yet he was defeated by AlphaGo. It is no easy feat to build a machine that self-teaches itself how to play the 3,000-year-old game Go. The total number of theoretically possible Go games exceeds a googolplex — that’s a 1 followed by 100 zeros — which is more than the number of atoms in the world. Yet, AlphaGo mastered it. This section dramatizes the five games played between a human and a machine, and in particular “Move 37” by AlphaGo that occurred during game three. AlphaGo’s move, so creative that only one out of 10,000 professional Go players could have made it, contributed to its victory. The commentators surmised that this AI had taught itself not just to excel at the game but also to employ one of the hallmarks of human intelligence: deep creativity. Another commentator ruefully added, “science was so rapidly progressing that it would soon drive us off the edge.”

Progress, so much a virtue in Western Civilization, justifies rolling over anything that stands in its way. However, elevating progress to the highest priority, as liberal societies are apt to do, deprives us of the norms and customs that guide our ethical choices. As portrayed by Labatut, von Neumann discarded any sense of self-restraint and devoted himself to pursuing the Holy Grail of science, no matter the cost. The novel highlights the “ultimate proof of the sway that irrationality held over the human race” and complicates our sense of certainty in scientific rationality. Religion begets fanatics, but apparently so does science. No doubt we will disappear, just like dinosaurs did, and science, that imperfect application of reason, might just fast-forward us to our end.

Nationality: Korean-American

First Language(s): Korean

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by: