Published October 8th, 2021

Review

by Lisa Schantl

Translingual, Calcutta born writer Amitav Ghosh is known for his well-researched and densely crafted works of fiction and nonfiction, often concerned with the relationship between the human and the natural environment. With Gun Island, his novel published in 2019 by John Murray, he creates multilingual and intercultural worlds for his readers to contemplate subjects such as climate change, migration, love, and world history.

At the center of the novel is a dealer of rare books, Deen Datta, who usually works in New York City but has come for a visit to his home town Calcutta. Expecting to go back to the United States soon, he is involuntarily dragged into an event that will change his future life: an excursion to the Sundarbans. He has been persuaded by his aunt to find a rare shrine of Manasa Devi, a Hindu goddess of snakes. The temple might soon be gone due to rising sea levels and it becomes Deen’s duty to record the structure with its inscriptions for future generations.

As one can expect, the excursion does not go as planned and Deen’s stay is prolonged. Tipu, a young man accompanying Deen on this trip, has a trying encounter with a giant snake and, after being bitten, develops visions that keep haunting Deen ever after. For the protagonist, the borders between reality and fantasy, fact and fiction start growing thinner. Returning to his apartment in Brooklyn does not ease his mind, and he decides to embark on a journey to find out more about the story that seems to be the root of his condition.

The frame for Ghosh’s narrative is the Bengali folk tale of the gun merchant (Bangla: Bonduki Sadakar). In this tale, which is loosely compared to Homer’s Odyssey in the novel, the goddess Manasa Devi wants a gun merchant as her devotee but he resists her and runs. In this myth, the goddess can be seen as a symbol for the more-than-human world, the spirits and subtle movements that remain hidden from the rational mind. The merchant, on the other hand, is a figure pointing to profit, trade and power. Later in the novel we learn that the legend might be based in true events that took place in the 17th century, just when the mind-body dualism gained force through Descartes in Europe.

In fact, the relationship between scientific facts and less explainable phenomena plays a main role in Gun Island. Asian mythology influences actions in the ‘rational’ West and Ghosh’s main characters who belong to the intellectual elite can be seen as stand-ins for the clash between feeling and reason. While Piya, a marine biologist from Calcutta, advocates the side of reason in the form of her scientific explanations and research, Cinta, an acclaimed professor from Venice who Deen Datta consults in his quest, argues that there are truths beyond our knowledge. Both strands come together in Deen, who is gradually warming up to the possibility of supernatural events.

In the novel, it is suggested that one way to encounter and deal with happenings beyond the rational is through stories. In one instance, Cinta says: “It is only through stories that the universe can speak to us, and if we don’t learn to listen you may be sure that we will be punished for it.” (141) And the more Deen listens, the more the causes of the at first incomprehensible events start unveiling themselves.

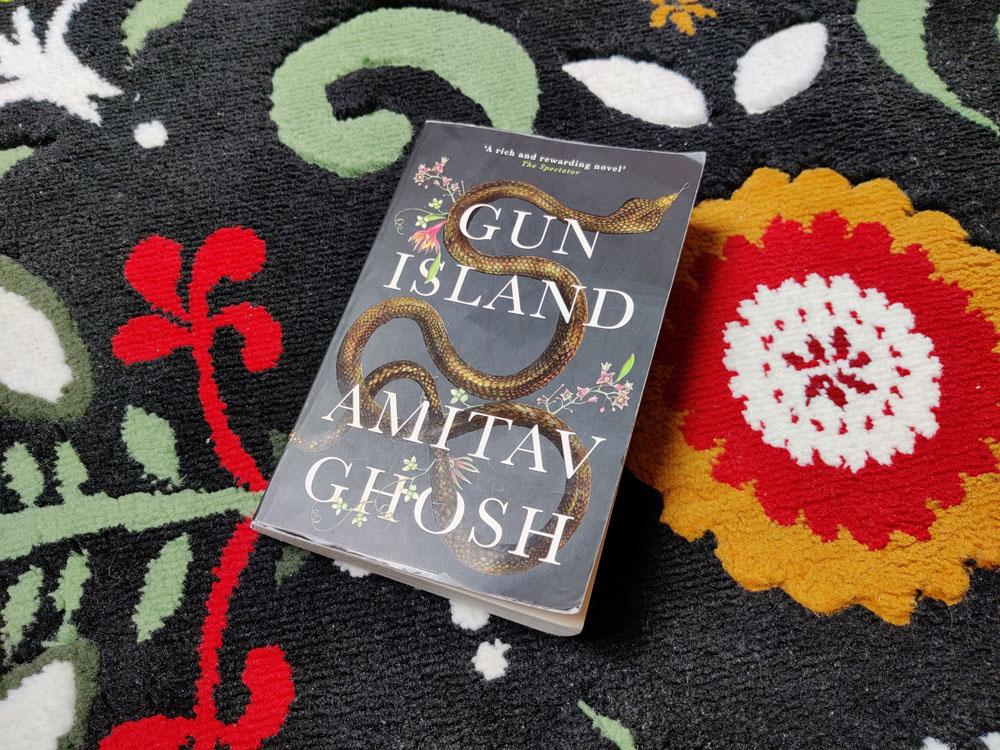

When I picked up my copy of Gun Island, my main motive was to read a non-Western climate fiction story. In my studies at university, I had focused on literature dealing with humanity’s interference with the natural environment, and the most pressing form of this interference — climate change — still plays substantially into my reading habit. The beautifully composed book cover showing a gigantic snake and exotic flowers and my previous knowledge of Ghosh’s nonfiction works in the field of ecocriticism did the rest.

Ghosh’s choice of spatial settings is one of the main reasons that climate change becomes a steady presence in the story: First, he places his protagonist in the Sundarbans, an endangered Indian mangrove forest; later, there is a brief stay in Los Angeles where wildfires are raging; and finally, the novel comes to an end in Venice, which is already sometimes referred to as the next Atlantis. However, since the Sundarbans are the root of the gun merchant’s tale, they remain the spatial anchor throughout the novel and most thought concerning climate change is given to their struggle for survival.

In fact, the group of islands has been considered endangered since 2020 due to loss of biodiversity. Individual islands are disappearing as they are swallowed by the rising sea and a power station is being constructed only few kilometers north of the Sundarbans which will cause further damage. Before the protagonist sets out for his excursion to this forest, the region is identified as “the frontier where commerce and the wilderness look each other directly in the eye” (9). As such, the Sundarbans become a strong image of the key conflict in the gun merchant’s tale, and the present meets the past, reality meets fiction.

The main character raising environmental concerns is the scientist Piya. She is leading a research project dealing with beachings of dolphins in the Sundarbans. Her voice is mainly heard in dialogical form, Ghosh’s obviously preferred way of mediating facts and relating to the actual world in this work of fiction. For example, we learn about an important detail for our understanding of the gun merchant’s story in a narrated lecture by a librarian: The period when the merchant fled from Manasa Devi from India over Egypt to Venice, the 17th century of Descartes, is not only the rise of rationalism, but also that of climatic disruption, the period of the so-called Little Ice Age. Undoubtedly, dialogues are an economic choice to add various details that would not have found a place into the story otherwise, but to me personally the style tends to be a little too clinical at times. I could not resist the feeling of being actually lectured about current and past events.

Ghosh’s extensive use of dialogue has, of course, also positive outcomes, especially when the writer gives the word to main and side characters to tell their personal stories. The power of dialogue and direct expression can be strongly felt in regards with the other main topic of this novel, migration. For example, one of the Bangla ragazzi in Venice is given a few pages to tell his arduous journey from India to the European capital of arts as a refugee. Ghosh has managed just wonderfully to bring such fictional accounts of personal hardship to life as he weaves these stories into one larger, multifaceted tale.

As a translingual writer who grew up in India and studied in Egypt and the United Kingdom, Ghosh’s intercultural and multilingual background could not but influence his writing. It might, in fact, also be a reason for his love for dialogue: This form certainly allows the author to casually mix languages other than English into his narration.

In Gun Island, the identified foreign languages are Bangla and Italian. They appear both covertly (the language stays the same but it is mentioned in the narration that a certain part is said in a different language) and overtly (the language used in the text actually changes by means of code-switching). Sometimes, Ghosh explains the meaning of the words right away, sometimes he does so with subtle hints, and at other times he leaves the understanding up to us. Soon, Italian speech tags and Bangla idioms start feeling like a natural part of the reading experience.

By implementing native idioms and intimate expressions, the readers get drawn into the center of the action. The use of foreign sounds and words inevitably brings us closer to the cultural backgrounds of the characters, although we might not be able to understand the other language. In a recent paper on Ghosh’s 2004 novel The Hungry Tide, Zakiyah Tasnim states that the author shows how “translating the full essence of a culture is not always possible” (2018: 149). This is certainly also true for the reader’s experience in Gun Island, as we might not be served a translation on a silver plate, but we are invited to grasp the words’ meanings as they speak to our emotions between the lines.

To wrap it up, Gun Island is a novel with many faces. It connects various story strands through the protagonist Deen and his at first not-quite-voluntary bonding with the legend of the gun merchant. Although not all of the strands are answered in the end and it can sometimes get a little crowded with topics of seemingly equal importance, Amitav Ghosh has created a climate fiction story full of cultural depth, which will undoubtedly make a book lover’s heart go faster.

Nationality: Austrian

First Language(s): German

Second Language(s):

English,

French,

Spanish

Supported by:

Comments on "A Powerful Translingual Cli-Fi Story — A Review of "Gun Island" by Amitav Ghosh"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login