Published May 16th, 2022

Interview

by Sam Dapanas

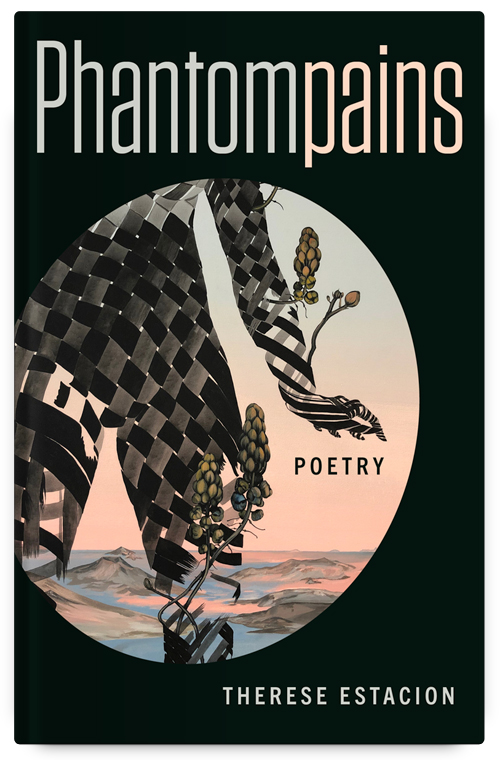

Therese Estacion is part of the Visayan diaspora community. She spent her childhood between Cebu and Gihulngan, two distinct islands found in the archipelago named by its colonizers as the Philippines, before she moved to Canada with her family when she was ten years old. She is an elementary school teacher and is currently studying to be a psychotherapist. Therese is also a bilateral disabled below the knee and a partial hands amputee. She identifies as a disabled person/person with a disability. Therese lives in Toronto. Her poems have been published in Contemporary Verse 2 and PANK Magazine. Phantompains, listed as Best Poetry of 2021, is her first book. https://www.thereseestacion.com

Sam Dapanas: Let’s begin with our shared native tongue, Cebuano Binisayâ. Your mother comes from Cebu and your father was born in Gihulngan City in the province of Negros Oriental, both in the Central Visayas region. Folks from Cebu City speak the dialect within Binisayâ language called ‘Urban Cebuano’ and those from the surrounding Cebu Province speak ‘Standard Cebuano’, while people from Gihulngan speak ‘Negros Cebuano’. So, as a kid in the Philippines, one has to learn, apart from English, the so-called ‘national language’, which is Filipino, based on the Tagalog spoken by those in the capital Manila. You and your family migrated to Canada, which has at least two official languages. How did these sociolinguistic layers evolve when you were growing up in the Philippines and later in Canada and how did they shape your views on writing?

Therese Estacion: Language acquisition was not straightforward for me as a child. There were a lot of conflicting messages regarding which language would prelude my belonging. I know my mother spoke a more ‘city’ version of Cebuano and my dad a more ‘rural.’ My dad’s maternal side is also Chinese-Filipino and sometimes spoke Fukien.

I never knew which language to fully embody. I would shift my Binisayâ depending on where I was and also used a hybrid version of English and Bisayâ. I went to a very orthodox all-girls Catholic school where it was mandatory to learn Mandarin, and I distinctly remember Bisayâ being banned in Grade 3. We were only allowed to speak in Tagalog, English or Mandarin. There was a definite language hierarchy, which I found confusing. I don’t think I was ever fully immersed in one language or gained true fluency.

I was 10 years old when my family and I immigrated here. I went to a predominantly white school in a poorer neighborhood. There was no support in terms of language instruction, no English language teacher or multi-language teacher (MLL being a more holistic pedagogical approach that cherishes one’s original language and sees its vital role in individuation). So, I steadily became more and more distant from the languages I came to the country with. I remember struggling to consciously think in Binisayâ when I started to notice the transition in my psyche from Bisayâ to English. Eventually, it became a struggle not to assimilate as I found my internal monologues narrated in English. In a sense, I accepted these implicit ideas that held English as a gatekeeper — a vernacular that would bring me a kind of cultural currency, one that would afford me certain possibilities and a sense of security.

So, my decision to write certain poems bilingually, as best as I can anyway, was my way of resisting the stronghold English had placed on my cognition. It was my way of reaching back to find and protect certain aspects of myself I had lost.

Dapanas: One of the earliest studies on the Cebuano Binisayâ poem — or the balak — was written by Francisco Encina, a Spanish friar from the 18th century. Encina wrote that “metafora” is an important feature of balak as a poetic form. And I love that the poems from your debut collection Phantompains: Poems (Ontario, Canada: Book*hug Press, 2021) made use of different ábat, monsters, (or as we Bisayâ call it, dílî ingon nátô, “not like us”) as bodily metaphors — the ukoy (merman) for limbs, duwende (gnomes) for cavity, agtâ (tree-dwelling demon) for eyes, tianak (or mantiyának, demon child) for uterus, etc. So, in a way, these retellings of folklore weaved with collective memory orally passed down to you do not just function as an attempt at cultural reconnection but something beyond that because it involves physical disability. Tell us more about this collection and being a woman of color writing what disability theorists call ‘crip poetry’.

Estacion: I wrote the ábat poems after I was discharged from West Park, the rehabilitation clinic I spent a lot of time in. It was a strange purgatory like time when I was well enough to be left alone at home, but still too sick to venture outdoors. I spent a lot of time alone at my parent’s house in my old bedroom feeling exiled. I wrote these stories to keep me company and as a way to articulate the horror. It was easier to write about my tragedy allegorically and connect to the bodily loss through myth-making. The poems afforded me a point of contact with my grief.

In terms of crip poetics, there seems to be a common theme of perceiving the Other as not oneself, but the Other as the object outside of oneself. The Self, then, has agency and a felt intelligence that gazes back to resist being projected on. The ábat poems attempt to do that by enticing the Other to come closer, only to really show what’s underneath — the anatomy of mourning. From here, my perspective cannot be owned or manipulated by the Other, and the Other is asked to experience my subjectivity.

Dapanas: A lot of your poems, particularly in the collection’s chapter “Blood and Absence Flows," are more or less odes to ancestors and, at the same time, a study on Filipino family terms — ancho, ama, ang kong, apo — depending on which ethnolinguistic group one belongs to. This reminds me of Indian novelist Arundhati Roy who wrote that for multilingual communities, “Translation is daily life, it is street activity, and it’s increasingly a necessary part of ordinary folk’s survival kit.” You have written acts of self-translation within these poems. Filipino fictionist Merlinda C. Bobis said about “the different languages [that] co-habit in one text,” that “translation begin as a decolonial urge that facilitates an empathetic collaboration among differences.” Do you have any thoughts on being a bilingual, if not a translingual poet, writing in and across languages?

Estacion: I wish I truly was bilingual! But I really am not. I’m a bit self-conscious that people might find fault in my attempts to blend Bisayâ into my poems or find the authenticity lacking, which seems to be a common Balikbayan conundrum. But I had an intention to write bilingual poems as a way to resist colonization, and ensure representation. I was very inspired by authors like Gloria Anzaldua’s and Eduardo Corral.

Also, growing up, it was assumed that I was Tagalog. By writing these poems, I wanted to let people know about my language and about the diversity of cultures and languages that exists across the islands.

Dapanas: I would like us to talk about the visibility of Filipino writings in Canadian literary spaces. Literary historians and scholars have pointed out the dominance of writers of Chinese and Japanese descent in Asian Canadian platforms. So, when we discuss Asian Canadian (or even Asian American or Asian Australian) literature, for instance, it’s mostly writers like Larissa Lai and Ken Adachi. But the same scholars would say there has been a growing visibility of Korean, Indian, Vietnamese, Arab, and Filipino writers since the 2000s, like playwright Ins Choi, essayist Julietta Singh, children’s author Thao Lam, screenwriter Zarqa Nawaz, and novelist Catherine Hernandez. How was your experience in terms of publishing so far? Tell us about this perpetual yearning for home and, at the same time, belonging in homelessness, which permeates Asian diaspora poetry in Canada.

Estacion: There’s a bit of a movement happening now in the Filipinx/a/o artist community here in Canada and an interest in publishing and enjoying artists from the diaspora community. I think about the magazine Living-Hyphen, the clothing brand Vinta Gallery, artist Marigold Santos, the comedy group Tita Collective, florist Kim Jasmin Monsalud Francisco, scholars and activists like Monica Batac and Francie Stohner, and other authors like Catherine Hernandez and Shirley Camia. I seem to have caught that prosperity wave and feel very fortunate to have my book out at this time.

Although, this theme of searching for home is one of the reasons why diaspora art is so desirable. One finds a type of melancholy in this type of artwork that exposes sacredness, but it’s not all melancholy. There’s also memory reconstruction, a search for collective and personal artefacts and symbols to metabolize them again. Diasporic art can be quite telepathic since it relies on synchronicities to fill in the gaps formed because one is so disjointed from home. In a sense, diasporic art is a conversation between the Self and the collective ‘the Self.’ I imagine my work has been a conversation in what psychoanalyst Winnicott calls transitional space, a space where two objects meet to create something new. A space where I can meet myself, the parts of myself that wants to exist and should have existed communally.

Nationality: Filipinx

First Language(s): Cebuano Binisaya

Second Language(s):

English, Tagalog-based Filipino

Supported by:

Comments on "Four Questions with Therese Estacion: On Speculative Poetry, Writing with/about Disability, and Filipino-Canadian Literature"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login