Published October 21st, 2024

Review

by Hantian Zhang

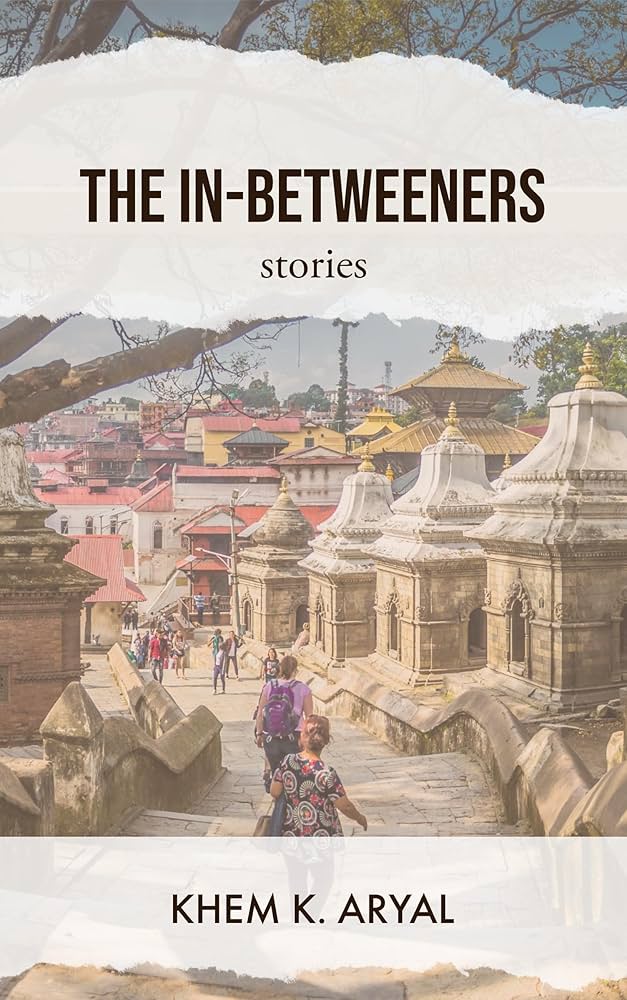

The In-Betweeners (Braddock Avenue Books, 2023) is a short story collection by Khem K. Aryal, a Nepalese writer and associate professor of creative writing based in Arkansas. Comprising thirteen stories, some of which first appeared in journals like Tint Journal, the South Carolina Review, Reed, and Pinch, The In-Betweeners focuses on the contemporary Nepalis’ immigration journey to the US, exploring the fault line where connections to the past are in constant tension with those forged anew in the new country.

In-betweeners are straddlers, people who live in two worlds at the same time. Their legs are of different strengths, though, as shown by the protagonists of Khem K. Aryal’s story collection, The In-Betweeners. Life in America is a struggle, and the life left behind in Nepal holds more contentment, more meaning, but why is returning never truly an option? Laxman Acharya, in the collection’s first story, “Laxman Sir in America,” used to teach Nepali in cotton trousers and a bleached white shirt, but after winning a diversity lottery visa and landing in the US, he goes to his picker job at an Amazon fulfillment center in blue jeans. The dignity back home is what he misses, along with familiarity with politics, which is why fellow Nepalis throw at him the same questions he always asks himself: “If you were so happy in Nepal, why did you come to America? If you believed so much you had a more dignified life in Nepal, why did you come to America?” It takes a friend’s request for money and Trump to realize there’s no return: He is already living in the new country, at the margin of it, yes, but still.

All thirteen stories in the collection share a theme: isolated protagonists struggling in the borderland between memory and reality. The collection’s cohesion lies in this thematic exploration of the contemporary Nepali immigration experience in the US, with the drama invariably centered on the family realm. All stories can also be located on the immigration timeline, at points when the original longing for the New World is already tinted by regret, and attempts at assimilation have turned the goal into an illusion. The protagonist, being a PhD student, a visa lottery winner, or an artist overstaying his visa, has set foot in the new country but does not fit in. Assimilation has been attempted but proven to be out of reach, so as a goal, it now only lies in the background, behind the minimal interactions with the autochthonous Americans. What occupies the protagonists’ minds is familial drama, the old-world ties transformed in and by the new environment: the relationship with the spouse, the Americanized second-generation, or the American colleagues. In all stories, these are the sites where tensions spark, where conflicts rise and demand resolution.

While some of the stories arch forward by less pronounced inflections like an epiphany, more find resolution in the element of the unexpected. In those where surprises are lurking, quick plot twists or unexpected peculiarities are how the narrative turns. In “Visa for Mama,” for example, a couple’s seemingly innocuous discussion about a visa application for a parent suddenly changes to something completely different when the husband throws in the information that the wife’s mother had long died. In “Overstayed,” an artist who has overstayed his visa is compelled to work illegally as a chef. He asks for leave to attend a Nepali show, but the boss shows up too late to approve his request. Instead of leaving to gawk at an empty stage, the artist improvises a show at the restaurant. The show is so successful that expedited visa processing is now on the table, which, ironically, triggers the overstayed artist’s determination to return home.

Another strength of the collection is its use of symbols and imagery to enhance the plot. My favorite story, “The Lucky Plant,” tells a husband-wife conflict partially through each’s pet plant: his is an orchid bought from a departmental auction, and hers is a bamboo bonsai christened “money plant.” The orchid, donated to the auction by the department’s taciturn chair, eases his interaction with America and hosts his dream of transplanting his family, but it is also not doing well and ends up being left in the snow to die. The bamboo, carrying the same nickname as the plants that had brought them luck back in Kathmandu, thrives in the new country, but once it blooms, it will expire. The couple’s quarrels are about the plants themselves — whose plant gets placed where — but also about children and their future, until the climax of the plant struggle brings out the wife’s secret. The story’s skillful pacing and deployment of symbols recall Jhumpa Lahiri’s “A Temporary Matter,” even though that story unfolds in non-verbal exchanges and subtleties, while Aryal’s is full of exchanges of fire rendered verbatim.

While successful in portraying the life paradoxes of the in-betweeners, some stories of the collection fall short in smooth, convincing plot turns. The husband-wife dynamic in “Election, 2017,” for example, reads troubling: The pair practically gets engaged on their fast date, but the intense emotion that supposedly fuels the swiftness reads missing on the page — the couple acts more like roommates, showing little interest in each other’s past. Granted, this marriage does not constitute the story’s mainline, but its thinness diverts the reader’s attention — this reader’s, at least — from the titular election, and I found myself exploring ways to rewrite the story. What’s the benefit from cutting the wife character? Or would simply strengthening the relationship to enhance the old-country ties do the job? I was keenly aware that I was engaging with, but not reading, the story as such thoughts ran across my mind; I wondered about the costs and benefits of the itch the author might not have intended but still stirred.

Perhaps, I felt the itch here because I am Chinese like the wife in the story, or, because the two months I volunteered at a Kathmandu primary school bring out a personal stake in getting closer to the characters’ lives. But as a first-generation immigrant to the US myself, I approach the story collection first and foremost from the identity position of an in-betweener, and it is from here that I appreciate the writer’s achievement in bringing out our struggles for the world to see.

Nationality: Chinese

First Language(s): Chinese

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by: