Short Story

by Khem K. Aryal

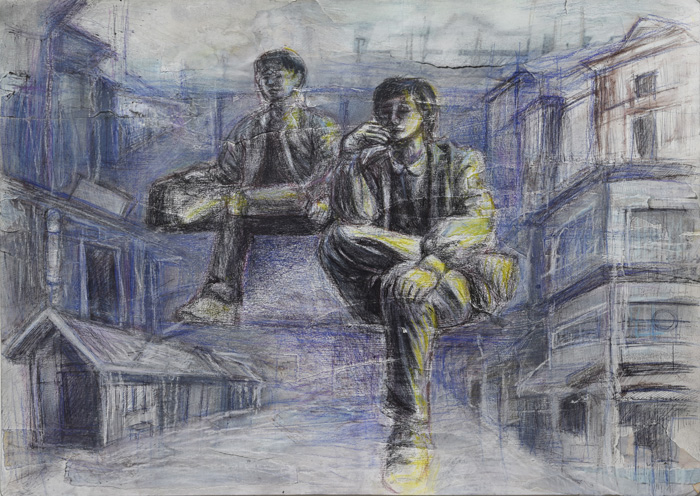

I was busy at the counter when Thapaliyaji dragged himself over and stood close to the coffee stand, staring at the customers. He wore pale blue rubber gloves, and hid a mop behind his leg. His muffler, worn over a black coat, with one end in the front and the other in the back with a loop for the neck, reminded me of cocksure village men I’d left behind. He had a thin beard and his hair needed a cut.

As soon as I locked the cash register he approached me. “Bhai Nepali ho?” he asked, arrogant as hell. Bhai, are you Nepali?

“Yes, dai,” I said, but he stood there without acknowledging my reply as if he not only gave a shit to my confirmation but also despised the fact that I was Nepali. Or else, he was a senior brother, dai, who I needed to bestow a proper greeting to, Nepali style, like “Dai, Namaste! Are you in good health? Will you please sit in this chair? I will stand, no problem! Sit here, please! Sit, sit!”

“I knew it,” he said seconds later.

“Sure, dai,” I said. “You joined us from today, correct?” I asked. Ahmed, the man who owned the gas station, had told me that there was a new hire, also a Nepali. He trusted Nepali guys, he’d said. I don’t know where this Iranian refugee might have heard it, but he also dropped the word “Gurkha” that I didn’t like. This new hire overlapped my coworker John, who did the morning shift, and me.

“I knew from your English,” Thapaliyaji said instead of replying to my question, as if what I’d asked was irrelevant. “You speak differently,” he added.

“Sure, dai,” I said. Thapaliyaji kept standing close to me as another customer approached the counter.

“Where did you work before this, dai?” I asked when I was free.

“I’m a social worker,” he declared, as if a social worker wasn’t supposed to work and I’d committed a crime by asking the question.

“Social worker?” For a second or two I got confused, but then I knew what he meant. He was not the kind of social worker who helped us file taxes at the community college where I studied and worked, or the social worker who helped us with paperwork when we visited the hospital without health insurance. It meant he was some kind of politician, and did nothing. Maybe he was a politician back in Nepal. I guessed he’d come to America on a diversity visa, which he would confirm later hesitantly.

As a new employee, he was primarily a cleaner. But Thapaliyaji was too dignified for the work. All the time he stood there interviewing me, he struggled to hide the mop behind his legs. When I got busy with more customers, he went to the coffee counter, pretended to wipe here and there, stared at some of the items, and examined the customers who either avoided eye contact with him or simply asked, “Hey buddy, how you doin’ today?” He dragged the mop randomly, and kept throwing glimpses at me. Then he was gone for the day.

When he got a chance the following day, he tramped to the counter again.

“You like working here, bhai?” he asked.

“Yes, pays my bills, as they say, dai,” I said casually. “The boss is nice.”

“Is he?” he asked dismissively. “Looks like a Musalté,” he assessed using the not-so-dignified term that they used in Nepal for Muslims.

“Yes, but dai,” I hesitated, “in America we don’t use that sort of language.”

He didn’t look impressed. He slinked away as new customers approached the counter. When he found me free the next time, he asked, “So, you like the Musalté?”

“How can you not like your boss, dai?” I began to clean the counter.

“I think you can get a better job,” he said as if he knew me better than myself. “Do you go to college?”

I said I was happy with the job. My boss was flexible and he understood if I had to adjust my hours due to my classes. I was good, no thanks!

He didn’t seem to listen to me, but still I said that much.

He didn’t insist, but when he was about to leave, he spoke. “You seem to be a laborious young man. Let me know if you need anything.”

What? I wanted to ask what he meant, but decided not to care. I said, “Okay, dai,” and he disappeared.

That night, though, it left me unsettled. What did he think of himself? Why should I ask him for help? Who was he? What did he know about me? As we slurped Ramen noodles, I told my roommate I had a new coworker who was an asshole.

Ramakant said I couldn’t allow myself to be distracted by somebody else’s behavior. He didn’t even ask who it was, but simply said, “He does his work, you do yours. Focus on your studies, mate. We are here for a purpose.” He’d taken a course in Eastern philosophy the previous semester to fulfil the general education requirement, and since then he’d started speaking like someone inducted into a circle of Indian swamis.

The following day I went to work thinking that Thapaliyaji had nothing to do with me. I couldn’t allow myself to be disturbed by what he thought and said. I’d do my work, while he’d do his. I wouldn’t even care whether he worked.

But as soon as he saw me free, he ambled toward the counter as if it were a rule.

“How’s your work going, dai?” I asked him before he spoke. I didn’t look at him and I didn’t say “Namaste” that I believed he expected.

He observed my work for a few seconds and asked, “Does this work pay your college fees?”

I wanted to ask him what he knew about colleges and their fees. Obviously, he didn’t know the difference between fees and tuition. But I didn’t have the time for it. We’d already spent quite some time inquiring into private matters yesterday and we were not supposed to waste our time like this. When we didn’t have customers, we were supposed to clean up, arrange goods on the shelves, organize accounts, and such. He was hired specifically to clean and to make sure that the coffee pods were full, and that the shelves were properly set. When he had time, he was supposed to wipe the windows and doors and wash the concrete around the gas pumps.

“Do you know there are scholarships for students like you?” he said as if I wanted him to help me. “I know some people at the college.”

When did I tell him where I studied? Never. Did he think he was still in Nepal? You know a couple people at a college, you go and use your influence, or threat, and get a discount on your son’s fees?

“Dai, if Ahmed knows we’re wasting our time like this,” I said, “he won’t be happy.”

“Tyo mujile ke garchha?” he asked. What will the asshole do? “How will he know it?”

I told him there were cameras; Ahmed supervised our work from home.

He hesitated. Slyly scanned around the counter to locate the cameras.

“Anyway,” he said as he went back to work. “Let me know if there’s anything I can do. We outsiders need to help each other.”

I didn’t want to see Thapaliyaji at work one more day. It was humiliating, and depressing to listen to him, especially because every day after that he kept coming with other things and suggestions that made no sense to me. I thought about telling Ahmed that the new hire didn’t really help the way he was supposed to do, and he would perhaps listen to me. But then I thought about Ramakant’s advice and also thought, the boss had installed cameras; why didn’t he do something by himself? I also thought it was no bravery to strip one Nepali of his job.

My coworker John used to say he had a Master’s degree in French literature. There was no reason why I shouldn’t have believed him other than that he told me the second week Thapaliyaji joined the store, “I wonder why this man works here. He seems to be brilliant. If he had a bit better English, he’d do very well.”

I asked him what he’d found so extraordinary in the man. He said Thapaliyaji had been a minister back in Nepal. He wondered how I couldn’t know him. “A country’s minister. Can you believe it?”

Stupid John! I said to myself. And that’s when I suspected his degree. But I was not interested in verifying if Thapaliyaji had been actually a minister back in Nepal. Why would I? Why should I care about it? Even if he had been one, I didn’t want to hear it from his mouth. I didn’t want a lying politician to be following me all the way to America. But that weekend, when he invited me to a gathering at the Nepali temple in Irving, I was curious to go. They were planning to help build schools that had been destroyed by an earthquake two years ago outside Kathmandu.

When I arrived at the temple, Thapaliyaji was talking to a dozen or so other Nepalis. As soon as our eyes met, he introduced me to the others I’d seen a few times but didn’t quite know. He said, “Yo bhai merai office ma kaam garchha.” This brother works in my office. I wanted to spit in his face and flee. When did I start working in his office? On top of that, he’d said “kaam garchha,” in the third person, using the lowest form of address in the hierarchy.

I left the meeting before it even started. The following Monday he walked toward me, saying, “Sorry bhai, are you angry with me?”

I said there was nothing to be angry about. I didn’t even want to look at his face.

“I consider you as my younger brother,” he said. “You are so much younger than me.”

“I don’t understand what you mean, but that’s okay,” I said. Then I told him Ahmed was complaining about the restrooms. They needed to be spotless. I asked him if Ahmed had spoken to him as well.

The color of his face changed to reddish black. But I couldn’t tell if he was angry with me or with Ahmed. He was angry, and I liked that. That whole day he didn’t come to talk to me again, but the following day he approached me aggressively. “Did you complain to the Musalté?” he asked.

“Why should I, dai?” I said. “He has cameras.”

“They are fake,” he replied triumphantly.

Ahmed entrusted John and I with running the store. He showed up occasionally and we talked over the phone. He was busy in his used car sales business that he’d recently started. When I asked him about Thapaliyaji the next time he came to the store, he said he was impressed by the man. “We’re working together for a loan,” he said.

“Are you?” I asked.

“He knows many people,” Ahmed said.

That day I considered changing my job. There were many other stores that could easily hire me.

When I shared my plan with Ramakant, he said I was being too sentimental. What kind of boy would consider changing his job because a new coworker made him feel uncomfortable? I wanted to explain that it was more than being uncomfortable, but I had no words for it. When he asked if Ahmed had told me anything, I had no reply. It only made me angrier with the so-called social worker. Ramakant said everything would pass. That night I spoke to my parents over the phone and I tried hard to convince them that I was doing well.

Thapaliyaji didn’t show up for work the following two days, as if he’d understood my affliction and decided to have mercy on me. His absence miraculously calmed me, and I even wished by the end of the second day that he was there asking me how I was doing. The next time he walked to me, with the same smug face, I asked him genuinely if he knew any source of scholarship at the college. Who knew? Money was always a problem, and if he could do something, that’d help tremendously. The loan that my father had taken to send me to America still waited to be paid back, and I still had two more years to go for a degree. Though I was not fully convinced, I’d thought after speaking with my parents that asking Thapaliyaji would do no harm.

“Sure, I can talk, bhai,” he said promptly. “Who should I talk to?”

That annoyed me briefly. “Didn’t you say you knew people?” I reminded him nonetheless.

He looked lost for a few seconds. Then he said, “Did I say that?”

Sala motherfucker! Get out of my store! I wished I owned the store and the authority to fire him.

“You said you knew people at the college,” I grumbled, utterly defeated.

“I know, but,” he said hesitantly.

“But you said it,” I repeated. “You said you knew people, and you could help.” I insisted as if I could make him know people by forcing him to admit that he knew people.

“I didn’t know you needed help, bhai,” he bleated.

That sent me to profound solitude. I didn’t look at his face; I didn’t listen to him; I didn’t acknowledge his existence for the rest of my day at the store.

When my classmates were preparing to fly to America after twelfth grade, I was haunted by the feeling that I’d been duped to have won a scholarship to study at the prestigious Budhanilakantha School. Why could I not go to America while all my classmates were ready to fly? Nobody had to tell me, though, I had no family members in America like many of them. Only my grades were not going to help me. I wasted a year hoping to fly to America. Finally, my father managed a loan enough to pay my tuition and board at a regional university in Arkansas for a semester, securing me a visa. By the time I transferred to Tarrant County College in Texas, my father had borrowed more to keep me going. If I didn’t do something very soon, my father was planning to sell a piece of land that he owned, and I was being mocked for putting the old man in such a crisis. What’s your son doing in America? everybody asked my parents, my mother often told me. Even those who worked in Gulf countries as migrant workers served their parents better.

“I don’t know why you had to lie,” I said to him.

“I didn’t lie, bhai,” he said promptly. “I never lie.” He waited and added, “You called me a liar, bhai; that’s not good.”

“Because you lied, dai,” I said, trying not to sound hurt.

“I was a minister in Nepal,” he said. “A minister, you know?”

It amazed me that he’d tell me he was a minister as a proof of his honesty. What kind of minister was he? Who didn’t know that all those so-called leaders lied? “Oh, dai!” I said, frustrated. “All those ministers lie; everybody knows it.”

“That is not correct,” he said, but looked trapped and began to drag his mop as if to free himself.

“Ahmed says you’re getting a loan for him,” I said. “Is that correct?”

“Bhai,” he said like a conspirator. “You know, they like it when somebody gives them hope. The Musalté needs money.”

“You talk like a politician,” I said.

“I am a politician.”

“I knew what you meant by social worker,” I said. “I thought I’d left those fake social workers back in Nepal.”

Was I going to support his fakery and keep Ahmed in darkness? Was I going to be his co-conspirator? A sense of guilt gripped me.

“Do you know,” he continued with a smirk, “why the Musalté was fine when I missed those two days?”

“Why were you absent?” I asked.

“We had a visitor from Nepal, a leader,” he said proudly. “Didn’t you read the news?”

I knew there was no news. “So Ahmed let you spend two days with your leader,” I said.

“I also invited him to meet Netaji,” he said like he’d accomplished a huge task. “He was thrilled.”

I quit the job at the store a week later. I thought that was the most ethical thing for me to do. Even my philosopher friend Ramakant agreed with me.

Thapaliyaji dashed into my new store from nowhere a month later. He wanted to buy a cigarette, and didn’t show any surprise at seeing me at the counter. Paying for the cigarette, he said he and Ahmed were opening a new recondition shop in Irving, their first venture together.

“Do you want me to believe you, dai?” I asked casually.

He prepared to light a cigarette without answering me.

“Best of luck, anyway,” I said when he opened the door. I was not sure if he heard me, but then I wanted to believe what he said was true.

Appeared in Issue Fall '19

Nationality: Nepali

First Language(s): Nepali

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi

Das Land Steiermark

Supported by:

Comments on "Thapaliyaji the Social Worker"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login