Published June 19th, 2023

Interview

by Sam Dapanas

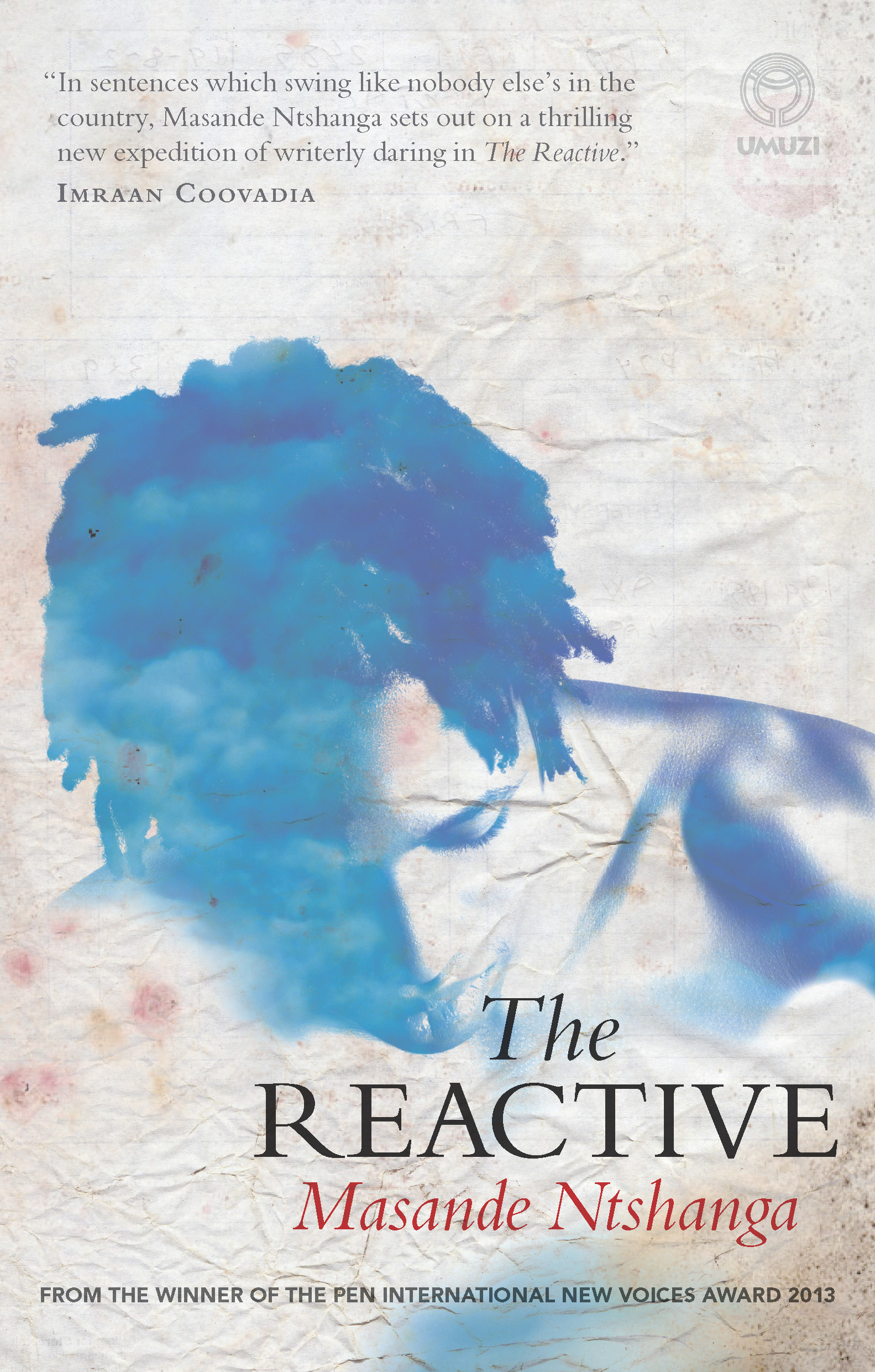

Masande Ngcali Ntshanga is a South African novelist, fictionist, poet, editor, and publisher. He has authored two novels—The Reactive (Cape Town: Umuzi, 2014), winner of the 2018 Betty Trask Award, and Triangulum (2019), published by Penguin Random House South Africa, Two Dollar Radio in Canada, and Jacaranda Books in the UK, which was nominated for the Nommo Award for Best Speculative Fiction Novel by an African. In 2020, he released his third book, Native Life in the Third Millennium, a collection of experimental prose and poetry. He has delivered lectures at the Gordon Institute of Performing and Creative Arts, The Beeler Gallery, The Columbus College of Arts and Design, the University of Cape Town-Centre for Creative Writing, and the SAE Institute for Creative Writing. His works have appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, MIT Technology Review, Berlin Quarterly, n+1, VICE Toronto, and PEN South Africa. A PEN International New Voices awardee and Civitella Ranieri fellow, he recently joined Rhodes University’s MA in Creative Writing program as lecturer and took over New Contrast Literary Journal as its first black editor.

Alton Melvar “Sam” M Dapanas: I would like to know where you are coming from, geolinguistically: born in East London, grew up in South African province of Eastern Cape, a place that is loomingly present in your works of fiction. You also write in English, the language of South Africa’s former colonisers.

Masande Ngcali Ntshanga: That’s an incredible question. Thank you. To be honest, from the beginning, language has always been an important element, or consideration, for me when it comes to writing. Not only its application as prose—which will always be essential—but also which language to select as an instrument for a certain artistic expression; and the politics that inform that decision. This isn’t only important to my work, but my own biography as well, as is the case with a number of writers from the African continent, dating all the way back to the African Writers Conference of Makerere University College, Kampala, in 1962, where a delegation of various African writers debated the use of English in African literature—a hegemonic, colonial language, as you’ve pointed out—and whether or not it was suitable for depicting the African experience. No sure conclusion was reached—a monolithic African experience remains just as elusive—but the conference forged a milestone in the continent’s literary history, nonetheless, with the dominant schools of thought emerging as either strict advocacy for the use of African languages or a conscious linguistic subversion of the European tongue in order to accommodate the unique perspectives, sounds and circumstances of the African writer. Having had no real hand in my own assimilation as a young South African born towards the end of apartheid, I’ve been placed on a path that aspires towards the latter, as championed by Chinua Achebe, although I both agree and hold a lot of reverence for Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s opposing view as expounded on in his seminal text, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), after which he resolved to write in his native language. That said, English is also the language I’ve read the most in, where I’ve discovered the writers that have remained with me, including African writers, who have been instrumental in instructing me on its possibilities and limitations as both a linguistic and artistic technology. To answer the second part of your question, it’s tragic but true that Anglophone writers, of which I am a part, are provided with a wider readership as well as stronger infrastructural support since South Africa’s publishing machinery, similar to much of the country’s institutions, are still founded on the legacies of apartheid and colonialism.

Dapanas: In Present Imperfect: Contemporary South African Writing (Oxford University Press, 2017), Andrew van der Vlies puts your name with Songeziwe Mahlangu in a lineup comprising of Gordimer, Coetzee, Marlene van Nierkerk, Ivan Vladislavić, Zoë Wicomb, and Ingrid Winterbach in the South African literary canon. Your coming-of-age novel The Reactive (2014) is also considered as a part of the second-wave post-Apartheid South African fiction by Lara Buxbaum who differentiated the second-wave’s skepticism and astonishment over the restorative narratives by earlier writers. Can you speak more about this generational aesthetics?

Ntshanga: As is the case with most post-liberation societies, I often feel as though our history is destined to be surprising in nature—to differentiate itself from what precedes it—and to do so increasingly, with more acceleration, as each epoch recedes into the past. This will always be the case, no doubt, even after the second-wave’s generational aesthetics, as you’ve mentioned them, and if anything, it has to do with the fact that each generation is confronted with its own unique set of obstacles. For example, this week, here in Johannesburg, we’ve seen campus protests at WITS University, where I was a writer-in-residence last year. For those students, and by extension, for the writers who emerge from them, skepticism is an ordinary state of being for being in the world in 2023, and the restorative narratives of earlier writers are indeed astonishing—as astonishing as colonial era writers would’ve been to writers working at the height of apartheid, all of them mission-schooled decades before the introduction of Bantu Education; or Gen X writers as opposed to millennial ones and Gen Z. In other words, the currents of our history are connected to our literature’s aesthetic preoccupations and vice versa. It’s part of why South Africa has always had a living literature, I believe, with each iteration indicative of its times.

Dapanas: Afrofuturism or Africanfuturism — the latter a term coined by Nnedi Okorafor in 2019 to mean African speculative fiction, or African sf — is ongoing in terms of its formation. In a sea of Afrofuturist writings from Malawi, Zimbabwe, and South Africa—from Shadreck Chikoti to Masimba Musodza, from Lauren Beukes to Keletso Mopai—where do you and your body of works stand?

Ntshanga: I’m not certain. I think that would mostly be determined by a reader or a critic. I do have a great deal of respect for speculative fiction as a genre, though, as well as for its practitioners on the continent. However, my works in science-fiction (Triangulum and “quiet earth philosophy” in Native Life in The Third Millennium) have emerged more from my love for the films and the books I consumed as a teenager. In fact, I feel more inspired by the subgenre cyberpunk (Blade Runner, Hackers, Ghost in the Shell, Akira etc.) than I do Afrofuturism or Africanfuturism as such. But I do understand how my works can be categorised that way since I have indeed written the speculative from an African context.

Dapanas: You write in both the traditions of realist and speculative fiction. I am curious about the choices you consider and the process you go through in ultimately deciding which modality to use for a particular short story or novel. Or are you instinctual in this aspect?

Ntshanga: It’s instinctual and, in large part, determined by the subject. I’m an ardent admirer of various modes of writing, of which realism and speculative fiction number only as two. Having said that, this is also influenced by writers I revere like Colson Whitehead and Samuel R. Delany, as well as filmmakers like Stanley Kubrick, all of whom have the ability to move through different modalities while maintaining the consistency of their voices as authors/auteurs.

Dapanas: You are New Contrast: South African Literary Journal’s first black editor since it was established in 1960. Can we talk about this elephant in the room—this long overdue appointment of a black editor of a 60-year-old literary magazine based in South Africa?

Ntshanga: Even though New Contrast has historically been a left-leaning journal, like much of the country’s institutions, it is, unfortunately, still at the mercy of the nation’s slow pace of change. This could be for any number of reasons, owing to both structural issues and otherwise, however, my focus, when I was approached to edit, was to effect a more visible change by transforming the demographics of the editorial team, as well as introducing new roles, such as having the magazine’s first Kaaps Editor, helmed by the brilliant Nathan Trantraal. This resulted in a widening of scope as far as the sample of writers we could discover and publish. The journal benefitted, and soon we were able to establish a rapport not only with a network of established writers, but all of these young artists, too, all of whom had previously felt excluded from the publication.

-okayafrica.com.jpeg)

Dapanas: Can you tell us about your experience in founding the experimental independent press Model See Media and the work that it involved especially that you founded it in 2020, the height of the Covid-19 pandemic?

Ntshanga: Model See Media, or MDL SEE, has been a joy to work on and experiment with. I’ve learned a lot since the 2020 lockdown, which gave me enough time to construct it. Established, initially, as a way to platform more experimental writing and literary forms, it was also a way for me to educate myself about publishing. It’s since grown into a conceptual project concerned with investigating the intersections between art, technology, commerce and society. South Africa has a host of impressive independent presses, such as Deep South Books in Makhanda, which champion works deemed too large a commercial risk at bigger houses. MDL SEE locates itself within this terrain, but is also distinct in that it’s function aspires to be as experimental as it’s published works, two of which, MDLSEE002 and MDLSEE003, are actually due out this year. This experiment includes operating as a pop-up publisher and having experimental roll outs, as well as being a non-profit that connects its literary themes to an engagement with their corresponding social causes.

Nationality: Filipinx

First Language(s): Cebuano Binisaya

Second Language(s):

English, Tagalog-based Filipino

Supported by: