Short Story

by Jee Ann Marie E. Guibone

“Your mother looks hideous.”

I absolutely agree, except I don’t say it out loud because you’re probably listening in right now, your spirit floating in the house, judging us like you always do.

“Wipe her face,” Tita Angela continues, knocking my elbow. “You have those fancy Korean makeup, right? With this storm, the manalabtan won’t be here till nine. You’ve got time.”

Never mind the prayer leader, I think, looking out the window to see the backyard all but flooded. The palm trees loom tall around the property like sentinels, slightly bowed but still standing. Nobody’s coming tonight, what with the storm.

I wonder if this house is going to get blown off in the storm. This is, what, a hundred years old? Probably older. I remember we used to have leaks in the ceiling. We put every bucket and pail we owned in the living room and kitchen to catch the rain. And then we used them to water the plants and flush the toilet.

God, the toilet — the outhouse, I mean. Every night nature called, I felt like I was doing an obstacle course: climbing over you and the old man, stepping over Ray and Cynthia, tiptoeing across the living room, opening the door to the patio, clambering down the steps twice the length of my skinny ten-year-old legs and running through the silong.

Every time, I looked up through the spaces between the wooden floorboards and watched out for your footsteps, heart hammering in my chest.

And inside the outhouse, the sole source of light was the moon. It filtered through the slits separating the walls and the corrugated tin roof. The only thing we could afford to turn into concrete were the walls around the toilet; paint was a luxury, so everything was brown and gray.

When I tell Tita Angela I didn’t bring my fancy-shmancy makeup kit with me, she gives me a disbelieving look. You know the one, where she throws her right shoulder back, raises her pencil-thin eyebrows high, and presses her chin down against her neck. Your sister is as dramatic as you; thankfully, not as loud or confrontational.

You, meanwhile, had threatened a full-grown man twice your size for short-changing you even a single peso.

A roll of thunder shakes the weak foundations of this ancient house, and the young boys try to see who can scream the loudest. Tita Angela silences them with a single “Saba!” and raises one rubber slipper in warning.

The teenagers check their phones, and one of them, fifteen-year-old Shayna Lynn, announces that there’s no signal. Tito Dodong slaps his thighs and wonders aloud if we should postpone the novena.

You would have said no. You would have knocked the back of his head and told him to exchange his basketball shorts for khakis and his faded Buffalo Soldier t-shirt with the fraying sleeves for a plain polo shirt.

I half expect you to open the casket, stand up and demand that the prayers start. Who are we waiting for? You would say. The Archbishop? The Pope? And you would turn to me and say, Stephanie, what are you standing there for? Get my prayer book. Useless! You’re useless! Every single one of you!

You with your face in clown makeup.

I chuckle.

I’m sorry, I can’t help it. You really do look ridiculous — not that it’s a surprise. Funeral packages are not known for the “natural” makeup look.

Maybe I should just leave you like that, looking like Pennywise the murdering alien clown. Do you know Pennywise? I bet you don’t. You hated horror movies. Or maybe you know now. Do dead people acquire world knowledge upon death? Posthumous wisdom-osmosis?

Will you haunt me if I don’t fix your face?

Not like it’ll make a difference. You’ve been haunting me since the day I left.

I get Ray and seventeen-year-old Jasper to take off the glass cover. I take a wooden stool from the dining room and sit beside your casket fashioned with elegant silver interiors and handles — the casket that I paid for, by the way. Not because I wanted to. I hope you know that, if it were up to me, you would be buried in flimsy cardboard.

But through emotional manipulation, Tita Angela guilted me into getting you a better-looking casket.

“What will the neighbors and relatives say when they see your Nanay buried in a cheap coffin? Her eldest daughter works as a fashionista in Spain, but she can’t afford to give her mother a nice burial?”

She had a lot of nerve trying to take me on a guilt-trip. Tita was there when you threw my things into the sidewalk; when you ripped my diary the minute you found out I had a girlfriend; when you threw me out of your life.

She was just there, standing in the silong, one hand clutching the front of her flower-patterned duster dress and the other wrapping around her young son’s shoulders.

I still remember how Lola Maming backed you up, standing at the top of the stairs, encouraging you like a devil on your shoulder, this old woman who never missed mass, prayed the rosary every afternoon, and read the Bible cover to cover.

You were banshees, both of you, screeching that mid-afternoon, bony fingers pointing at me, casting a hex on my life, calling for my death.

You knew why I never came home for her funeral. You knew. Yet you told everyone who would listen that I was ungrateful, rebellious, head so big with my own achievements that I had floated up to the sky like a balloon.

You weren’t far off. Leaving you, leaving this place, was like floating in the sky. You weren’t there to hold me down — no Useless! Stupid! Lazy! to wrap around my ankles like chains, no Ingrate! Heretic! Devil! to circle my neck like a leash.

You were my shackles, mother dear. And the day you threw me out was the day I became free.

That was, perhaps, the greatest gift you had given me.

But now I’m back in this house after so many decades. You have a bathroom inside the house now, thank god. The floorboards seem new, cherry-red and smooth, recently varnished. Looks like you made use of your nephews and nieces, not to mention Ray and Cynthia, one a civil engineer and the other a public-school teacher.

They’re weird around me, Cynthia overly polite and Ray awkward like a teenager, unable to meet my eyes. They don’t know me.

Oh, they remember their nineteen-year-old big sister carrying a backpack and a woven plastic bag filled with everything she owned under the sun as she walked away from the only home she had ever known. They remember me sharing a box of Curly Tops chocolates with them. They remember us fighting over the last cheese-filled puto during fiesta. But they don’t know me.

They don’t know that I landed in Spain on a scholarship and worked two jobs for rent and food. They don’t know that my girlfriend broke up with me because I befriended the liquor store.

My only siblings don’t know that I crawled my way out of the bottles of pills and spirits to pull myself together — and still I feel like a weathered old t-shirt, washed out, threads unraveling at the seams, filled with holes. Or maybe I’m an old jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces and corners bent and scorched by careless hands, the rough passing of years, and the memory of an old woman’s bitter anger.

No one in this house knows who I am. You made sure of that.

Yet here I am, on special request.

“Your mother wanted to see you, you know,” Tita Angela had said, that arsonist who spreads guilt instead of fire, watching avidly as filial obligation and societal pressure licked at my heels like flames. “Before she died, she told me to find you and ask you to come home.”

Did you really? Did you want me to come home? Or did she only say that so she and everyone else can feast on me like vultures. They circle around, watch my every move, and whisper when they think I can’t hear them.

Even now as I wipe your face, I can feel eyes on me.

Your skin feels so strange. It’s a little rubbery, a little soft. I wipe the lipstick off first. It’s a dark red, something you would never wear. Come to think of it, I don’t know how you look with makeup. I don’t remember an instance when you so much as wore lipstick. The closest you got was a swipe of lip gloss for my grade school graduation.

Next to go is the powder that sits on your face like a sheet of paper, too white and obvious. Tita Angela was right. Your visitors will take one look at you and murmur about your makeup. It will be the highlight of their evening — second only to the news of your prodigal lesbian daughter coming home to pay her respects, of course.

Now that all the makeup is gone, I take out Tita’s BB cream and spread it on your face. We never got to do this, did we? You never taught me how to do my hair or wear makeup. I learned the first one from my first-grade teacher and the second one from the gays at the salon next to my high school.

What are you going to do with makeup? you once said. Don’t be a slut. You don’t need that to get good grades. Focus on your studies.

I push a bead of cream across your cheeks and stretch the skin a little bit, my hands itching to pinch, to hurt. You’re already dead anyway. You don’t care, do you?

Then I take a deep breath and spread the cream evenly.

You know, I think this is our first mother-daughter bonding experience without the insults and physical pain. Isn’t that funny?

I press setting powder on your face and move on quickly to your eyebrows. They were always so sparse, like scattered bamboo trees. They made you look like a witch, I secretly thought, especially when you talked in a high, reedy voice.

What color should I use on your brows then?

Ash or gray to match my hair.

The closest shade in Tita’s palette is an ash brown. I paint your brows softly, the hairs responding so gently that, for a moment, I forget you’re a corpse, cold and silent, unable to scream and hurt.

Eye shadow?

A natural shade. Maybe light brown, a little rose pink?

I’m impressed. You’ve got good taste!

I blend the shades and lean back to admire my work. Can you see yourself? I did a better job than the one from the funeral parlor, right? Even you can admit that. Tell me I did a good job.

You did. You are very talented, Stephanie.

The blush and bronzer are next. I mean, sure, everyone knows you’re dead, but you don’t have to look dead. The bronzer gives your face a soft definition. I blend it in and marvel at your jaw. Obviously, it’s stiff now, trapped shut with wire, or so I read on Google.

Nanay, why did you hate me so much?

Hm?

Oh, now you’re quiet. Now, you’re giving me the silent treatment after you’ve been haunting me all these years.

“Wow, you’re good,” Cynthia says, appearing over my shoulder. Her long dark hair swings like that bead curtain framing the door to the dining room. “She doesn’t look like a clown now.”

I giggle and turn to her. If she’s gonna be buried with makeup, she should at least look good, I say.

Cynthia gives me a considering look, her eyes soft, her lips frozen in a disappearing smile. Her face is tanned and smooth, no pimple in sight. She’s twenty-seven now, a fully functioning adult, with a policeman boyfriend I’ve only seen in her Facebook photos.

“Do you have your own salon in Madrid?” she asks, turning back to look at your immobile face.

No, I say. I tell her that I’m actually a fashion designer. I run a small boutique that specializes in wedding attire and jewelry. My designs have been featured in Spanish movies and TV shows.

“Wow,” Cynthia says again and wrenches her eyes away from you. She leans casually against your casket. “I’d love to visit you. I’ve never been abroad.”

Just tell me when, I say. I’ll give you a tour.

And her smile is wide.

Because she can, if she wants. She’s free now. You can’t stop her. You can’t disown her or humiliate her for not doing what you want.

“What lipstick are you gonna use?” she asks.

I sift through the expired makeup in Tita Angela’s bag (“Take these, so that I can finally throw them out after you use them.”) but come up short. There’s no lipstick.

“Maybe there’s one in Nanay’s room.”

I doubt that, and I tell her so.

She shrugs. “Well, you never know. She might have been hoarding makeup since the seventies.”

We both chuckle, the tension of being in each other’s unfamiliar space softening.

“The manalabtan just texted!” Tita Angela shouts into the living room. “She’ll be here in thirty minutes. Cynthia, find your mother’s prayer book!”

I’ll do it, I say, standing up. Hopefully there is a hoard of vintage makeup in your room.

I climb upstairs. It’s right outside the room you and the old man once shared before he died.

Bad liver, drank too much, Tita Angela the family historian told me.

I step into your former space and flick the switch on. There’s only one light in the middle of the ceiling, and it casts everything in yellow. The walls are made of thin wood. The timber columns haven’t been replaced since I last saw them. The foundations of this house have remained the same.

But there are marks of change. The toilet, the new furniture, the beaded curtains. Those must have been your decision. Nothing happens in this house without your say-so.

But now you’re gone. What does that mean for everyone?

Your bed takes up most of the space, pushed to the left for the altar on the right. A Santo Niño holds court in the middle of the table. Behind it is a framed illustration of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Christ looking like a white European model. A small statue of Our Lady of Perpetual Help stands next to it. There’s a bunch of rosaries tangled together over some prayer booklets.

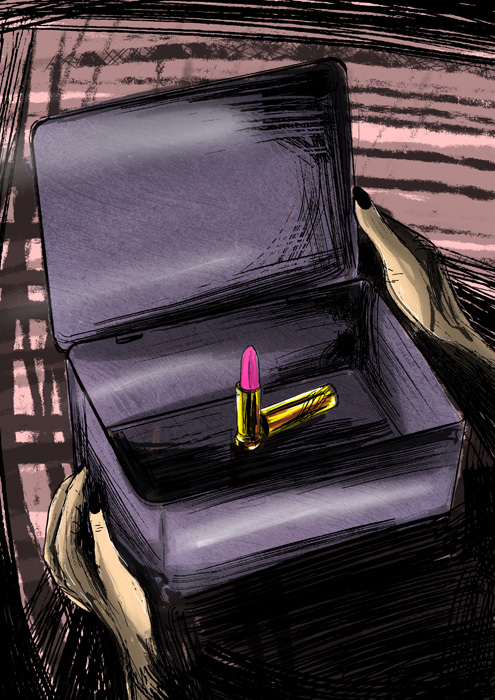

And beside them is a tin box that used to contain biscuits. Curious, I open it, fully expecting a sewing kit. Instead, what I find are folded pieces of paper. They’re yellow and smudged brown, the blue ink bleeding through the back of the paper. And in the corner of the box is a tube of lipstick.

It’s a Coty 24.

A loud slap echoes in the room. I jump, throwing the lipstick back into your box.

Another hit, flesh against flesh, rings next to my ear, and I turn around.

And I see you.

Words are being thrown around, but they’re garbled like you’re underwater. No, I’m underwater. I’m… peeking in from behind the door. I’m watching and listening, immobile, frozen.

The old man is hitting your head, holding your arm. The lipstick sits on the altar. He points at it, grabs it, and throws it against the wall. It breaks in two.

He shoves you against the Sto. Niño. A small statue of a crucified Christ tumbles and shatters. When he turns toward the door, I unstuck myself, stumble backwards, and run. I leave you behind.

The memory fades as quickly as it appears.

I turn back to the lipstick and cradle it in my hands. I can see it now, the jagged lines where you had smeared Rugby glue to repair it. I pull at the ends, but there’s no give. You patched it up really well.

A Coty 24. A real vintage find, this one. I take off the cap. The lipstick hasn’t been used at all. It looks new, the creamy pink color a little off but the texture is still smooth.

I look at the folded pieces of paper and open them one by one.

Dear Celia.

I haven’t heard your name in a long time. I mean, you were never “Celia” to me. You were “Nanay”. And after I left, you were someone I dared not name.

I scan the bottom of the letter and an unfamiliar name jumps at me. Love, Bernadette.

I open the other letters. Love, Bernadette. Yours, Bernadette. Always and forever, Bernadette. Bernadette, Bernadette, Bernadette.

A hollow kind of anger starts to consume me, like someone is taking a spoon to my chest, scooping out my heart and my ribs and all my insides. I feel so empty, a spacious cavern filled with nothing.

You betrayed me.

You — you were like me.

You could have been my greatest ally.

You could have protected me and supported me and loved me.

Instead, you saw in me everything you could have been but was afraid to be. And you drove me away. You threw me against the wall, watched me break, and left me to glue myself together.

Why won’t you say anything now? Why aren’t you talking?!

I throw your stupid box on the bed; I tear your letters in half and scatter them in the air.

What are you gonna do now? What are you gonna say?

You’ve haunted me all my life, but now you won’t talk. Now, you’re quiet. Now, you’re distant. Now, you’re gone!

My knees give way, and I fall on the altar, knocking the statuette over. I drop my head against the Sto. Niño. Hot tears press against my eyelids.

A strange warmth covers my shoulders like a shawl. Silver hair falls over my face. Calloused hands run over my cheeks, but my eyes remain closed.

When I do open them again, I’m alone.

But there’s a piece of paper caught on the edge of the table. Dear Stephanie, it reads. I look around at the torn letters and begin the process of piecing them together.

***

“Where have you been?” Tita Angela shouts, grabbing my arm as soon as I step down from the stairs. “The manalabtan is here, as well as the neighbors! Clean up the casket while I hand out the coffee.”

I walk over to you and take out the Coty 24. I apply it to your lips, whisper-like, just a touch of color. It doesn’t slide as smoothly as I would have wanted, but it does the job. It coats your lips in a soft natural pink.

“Is it done?” Cynthia asks, standing beside me. She looks down, and her brows are raised. “That’s amazing!” She lets out a soft sigh. “She looks beautiful.”

I place an arm around her shoulders and lean in. “She does, doesn’t she?”

Appeared in Issue Spring '23

Nationality: Filipino

First Language(s): Cebuano/Bisaya

Second Language(s):

English, Tagalog

Das Land Steiermark

Listen to Jee Ann Marie E. Guibone reading "Coty 24".

Supported by: