Short Story

by Anna Pedko

Her grandmother was the last person Svitlana went to say goodbye to before leaving. Not because she didn’t have any warm feelings toward Granny but because she had too many of them. They were choking her, making Svitlana unable to speak without a tightening pain in her chest. Her hands were shaking. Eyes prickling.

Grandmother was the main reason Svitlana didn’t want to leave her village. She was the one who had raised her, taught her to read, treated her scraped knees when she fell off her bike. Who spent long evenings with teenage Svitlana, listening to her secrets about the boys she liked and the girls she trusted. Support. Foundation. Home. That’s what Granny was.

Svitlana felt like a traitor for leaving for Canada. The bitterness of letting Grandmother down corroded her from the inside, like rust. Yet, at 20 years old, she knew she couldn’t sacrifice another decade of her life to this little village, no matter how strong the affinity of souls was between her and Grandmother.

She felt like she was only going through the hollow motions here. She wanted to be seen and live among skyscrapers, not spend her days digging in the dirt to grow tomatoes or herding geese back into the pen when they ran off.

She sat across from Grandmother at the wooden kitchen table, chipped at the corners and warm from the sun. The silence stretched like dough between them, tender and comfortable.

“Babusia,” Svitlana whispered, her voice cracking. “I got my visa. I’m leaving next week.”

Grandmother didn’t move at first. Just looked at her with those silver-threaded eyes — eyes that had seen wars, famine, love, and loss. Then she smiled. Soft. Bittersweet. Kind.

“Tak i znala,” she said. “I knew it would come.”

Svitlana’s throat clenched. “Aren’t you... aren’t you mad?”

Granny reached across the table, her fingers like dried leaves, warm with wear, quietly weathered, and placed them over Svitlana’s trembling hand.

“How could I be mad at you for growing? A bird must fly. You were never meant to stay in the nest.”

Svitlana shook her head, tears spilling. “But I’m leaving you alone. It feels wrong. It feels like I’m... turning my back on everything good.”

Granny wiped one of Svitlana’s tears with her thumb. “You are not turning your back. You are walking forward. And every step you take, I’ll be behind you, inside you. I raised you for this.”

“But who will bring in the geese when they run off?” Svitlana laughed through her tears.

“Let them run,” Granny chuckled, her own eyes wet now. “Even geese must stretch their wings.”

They sat there, hand in hand, hearts breaking and yet somehow fuller than they had ever been.

After a while, Grandma went into the back room. When she returned, there was a small bundle in her hands. She sat down on a chair that creaked, as if the old thing was grumbling at being disturbed again, and unwrapped the bundle.

A linen, hand-stitched blouse. Vyshyvanka. Ukrainian national clothing.

“This was my mother’s. She wore it when she crossed the border during the war. I wore it the day I got married. Now it’s yours.” Grandmother patted Svitlana’s shoulder.

Her breath caught. This was more than a shirt. It was a story stitched by her ancestors, a lineage sung in color.

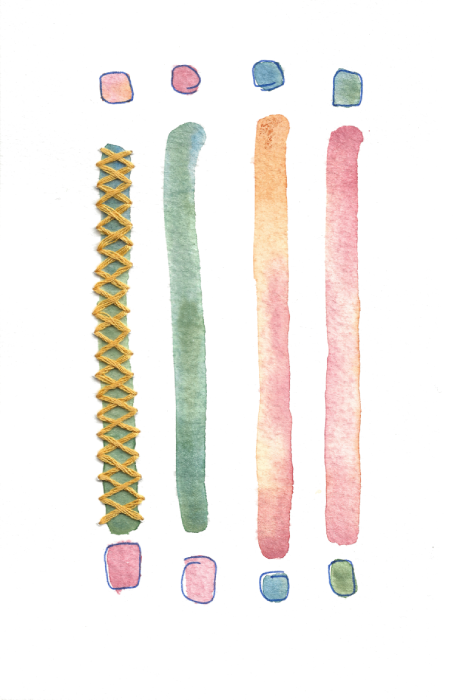

Every stitch on the white cloth was a language of resistance, identity, and unity. To wear it was to carry forward centuries of pride and perseverance. The chest and sleeves were framed with dense, geometric patterns — diamonds, stars, and traditional crosses — stitched so tightly they formed a near-tapestry.

Each geometric motif carried meaning — wishes for health, harmony, and strength. When wearing it close to the heart, the vyshyvanka wrapped the soul in belonging.

Svitlana ran her hand over the red thread woven into patterns across the chest and sleeves. The embroidery was slightly uneven, whispering of hands that trembled from years, not lack of skill. The seams were frayed. The fabric soft with decades. It smelled of cedar and brown soap.

“Someday give it to your children and tell them it was from their great-grandmother,” Granny added with a smile.

In Toronto, everything moved faster.

The buildings were steel and glass, their windows reflecting clouds like they were trying to trap the sky. The air smelled of coffee, bus exhaust, and urine — the kind of air that had never touched wheat fields or carried the scent of late-summer apples from a family garden.

People smiled with their mouths, not their eyes. Svitlana learned to smile back, even when she didn’t mean it. Especially then.

At her new job in customer service, she wore gray slacks and pale blouses, buttoned high, wrinkle-free. Nothing that told stories. Nothing that made her stand out.

The vyshyvanka stayed in the drawer under her bed, folded carefully between layers of tissue paper like a relic. A bundle that warmed her soul with memories of home. Sometimes she would take it out and wonder if she should wear it outside. But each time, she folded it back up. Some things weren’t meant to be worn in public — they meant too much.

Too folkloric. Too loud. Too sentimental.

Too much.

Her name became Lana. Not because she wanted it to but because her manager had squinted at her application and said, “Svit… Svee… You know what, let’s just say Lana. It’s easier.”

Easier for whom? she wanted to ask. But she only nodded.

Over time, even her new friends forgot what her full name was.

She laughed when they called her Lana, signed her emails with it, picked up the phone with it. She spoke it into the mirror.

But she missed the sound of her own name — an ache that grew deeper each time she ignored it.

Svitlana had been a girl with soil under her nails and sun-warmed raspberries in her palm. Lana was someone who microwaved dinner and paid rent on time.

She had traded a name stitched in meaning for one that fit on a coffee cup.

But she hadn’t lost everything. Not really.

Over time, she found pieces of herself again, scattered like seeds that only needed new soil. At first, it was just a flyer someone handed her at the subway — Ukrainian Cultural Festival This Weekend. She almost tossed it. Almost.

At the festival, the music was familiar. So were the voices. Svitlana hadn’t realized how much she had missed the melody of her language until she heard it spoken all around her, without apology. There were folk dances and borshch and old women with scarves tied under their chins selling hand-stitched crafts. A man was playing the bandura. Children ran past in vyshyvankas no different from hers.

The next year, she wore it. Grandmother’s blouse. She kept her doubts on a tight leash as she stepped outside, heart thumping in her chest, the fabric warm against her skin. No one stared. A few people smiled — real smiles, with their eyes.

That day, someone called her Svitlana.

And she felt at home. For the first time since leaving her birth country.

She started volunteering on weekends at a community center that helped Ukrainian newcomers. She taught them how to navigate the buses, the resumes, the government forms that made no space for soft consonants or long vowels. In doing so, she began to reclaim the parts of herself she’d folded away — like a blouse under tissue paper, waiting for the right day.

In time, she stopped seeing her two lives as a fracture.

Toronto had taken some things from her — but it had given too. Space to grow. Safety. The right to speak her language and still belong.

To love another place without losing the first.

Appeared in Issue Fall '25

Nationality: Ukrainian

First Language(s): Ukrainian

Second Language(s):

English

Stadt Graz Kultur

Listen to Anna Pedko reading "Stitched":

To listen to the full-length recording, purchase one audio recording in our Ko-fi shop, or unlock all recordings with a monthly subscription.

Supported by:

Comments on "Stitched"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login