Short Story

by Viktorija Curlin

“Come buy our orchard fruits! Sweet to tongue and sound to eye, come buy, come buy!”

So sang the elven merchants by the water, each and every day. Workday or Sunday, dawn or twilight, I could hear them thumping about and crying out.

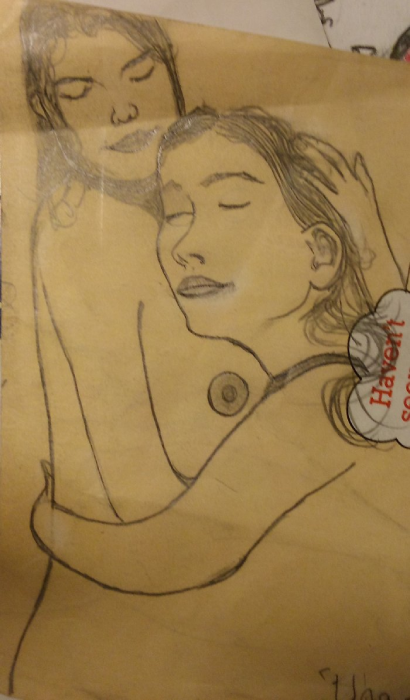

That evening, Lizzie and I were sitting among the brookside rushes, as was our custom, listening to the murmur of the stream and the whispers of the wind in the furze bushes. The air was brisk, so we crouched close together, our hands clasped. I felt the soft tips of her fingers tingle against mine; I bowed my head to her, and her cheek was tingling too. When I turned to look at her, she looked away, trying in vain to hide her blushes.

I sighed.

I turned my eyes towards the brook.

We had been together all our lives — or, at least, as much of my life as I could remember. Our home was small and modest, but we furnished it with our love. We shared everything: our meals, our baths, our joys and sorrows — we even shared a bed. I felt Lizzie closer than a sister. For her smile, her kiss, I would do anything. I would go to the end of the Earth to bring her heart’s desire.

If only she desired the same thing I did.

The thought was a painful one. I gazed down the overgrown shores, and through the curling mists in the distance came the song of the elven-men.

“Here they come,” I mumbled. “Come, lie close.”

We must not look at the elves, I knew. We must not eat their fruits. Who knows upon what cursed soil their magical orchard fed its hungry roots? I knew I mustn’t look — yet I couldn’t resist the temptation. I wondered what their fruit tasted like. If it was even one hundredth the sweetness of Lizzie’s laughter, one hundredth the joy of making her smile, I would —

The elves moved slowly down the glen, crying, “Come buy!”

Lizzie became fretful. “Laura, you shouldn’t look at them!” She shut her eyes, and snuggled closer, trying to hide from their view. I put my arm about her shoulders, held her closely; so close, I could feel the beat of her heart.

“Look, Lizzie,” I whispered, the rippling of the brook nearly drowning out my voice. “A host of ugly little men are coming. They carry baskets, plates, and golden dishes. Oh, you should see how luscious their grapes are! Their vines must be fairer and the winds in their garden warmer than any place in the world!’

“No, no!” Lizzie gasped. “It’s all charms and tricks, Laura. Their gifts are poison, and would harm us.”

I said nothing. The cries of the merchants grew louder and louder, until Lizzie could stand them no longer. She put her fingers in her ears, sprang to her feet, and ran as if the devil himself were at her heels. Watching her stumble up the glen, I nearly laughed. What a child she still was. Once she was out of sight, I turned again to the elves. Their faces were more like faces of birds and beasts than the faces of men; they might have terrified me, were their voices not so starkly different: mellow and soft, like doves cooing a love song.

Something within me stirred. Like a lily rising from the beck, some deep and dark longing which had lain dormant and kept to the far reaches of my heart, spread its limbs and stretched its neck. My thighs ached and my insides smarted, until it became too much. Like a ship when its mooring line is loosened, I launched myself up on my feet and went to meet the cackling elven-men.

They swarmed towards me, capering and crying; but when they reached where I was, they halted and began to leer slyly at each other, signalling and whispering. One of them set down his basket, another reared the golden plate, while many took to weaving a crown of brake, thistles, and brown nuts, the kind I hadn’t seen sold in any town. They put the crown upon my head. They set the golden dish of fruits and berries in my lap.

“Come buy,” was all they said.

I stared, but did not stir. Though the crown was heavy, my head felt light, made of air. The smarting inside me grew into a flame. I ached for a taste, but had no money. The merchant kept goading me, biding me to taste the dish, his voice enthrallingly sweet and smooth. I shook my head, tried to gather my wits.

“Good folk, I’ve no coin. I couldn’t possibly take your goods when I’ve nothing to pay you with.”

“Surely you have something,” the merchant said with a wide grin.

Again I shook my head. “Nothing. Not a penny. I am sorry.”

But the elves sneered at my excuses. The merchant stared at me with a strange look in his eye.

“There’s plenty gold upon your pretty head,” he said. “Your lovely curls will do. Buy from us.”

“Come, buy!” they all said in one voice.

I gazed at the lush fruits in the golden vessel. I knew, at once, that there was no question of whether I would pay their price. I always carried with me a small pen-knife, which I now took out of my pocket; I pulled a pin out of my hair and brought the blade to the loose lock. When I cut, I closed my eyes, and pressed out a single tear.

The elves must have collected their payment and left just then, but I was scarcely aware of their presence. As soon as my precious hair was surrendered, I thrust my hand into the vessel, brought a pome to my lips, chewed it, and sucked the globe whole. Oh, what sweetness, what ecstasy! Honey was nothing to it, wine paled in comparison to its strength. I sliced a peach open, took out the stone, pressed my fingers into the pit of the fruit, and fingered the flesh apart. Juice flowed, running clearer than water from a mountain spring, drenching me head to toe. I had never tasted anything like it. I sucked and sucked and sucked, until my lips were sore, my face and flower crown soiled. Then I threw the empty rinds away, all save one kernel stone, which I gathered in my handkerchief and put it in my pocket.

Alone, filthy, and on shaking legs, I went home.

Lizzie ran out to meet me at the wicket. She put a stole about my shoulders and took my arm in hers. Her pretty blue eyes were clouded with worry.

“You shouldn’t have stayed so late, Laura. You know how dangerous it is at night, and with those elven men on the prowl.”

I said nothing as she ushered me into our snug little cottage. She had me sit by the fire, brewed me tea, and rubbed my cold feet back to life. Her fright was subsiding, but did not go away entirely. She glanced up at me as she was kneading my feet, with a look of concern and reproach.

“Laura, do you remember Jeanie?”

“Who?” I grumbled.

“Jeanie, the miller’s daughter.” She frowned. “You must’ve met her, many times. Anyway,” she continued when I looked away, “last autumn, one night, she met the elves. She took the gifts they offered, ate their fruit and adorned herself with their flowers. At first she was in a blissful trance, but soon enough she began to waste. She pined after the elves’ fruit, but though she kept seeking them out, she never saw them again. So she dwindled and faded, and with the coming of winter she passed away. Do you know, ”she said, in a strange voice, “that no grass will grow on her grave? I planted daisies there a year ago, but they never bloomed. Nothing lives in that soil, not even weeds.”

“I don’t see how soil has anything to do with the elven merchants.”

Lizzie turned to me with a desperate look, her eyes threatening tears.

“Laura, you must promise me. Promise you shan’t loiter after night falls, and that you shan’t seek out the elven-men!”

Again I almost laughed at her. She was a child, a pigeon! I had tasted the divine.

“Hush, hush, my sweet sister,” I said. I cupped her face in my hands. “It’s too late; I have already eaten, and ate my fill. But,” my voice faltered, “my mouth still craves those heavenly fruits. Tomorrow night I’ll have to buy more.”

She was astonished. She stared at me with her mouth wide open. I smiled, and laughed, and kissed her on the cheek. “Don’t be sad, dearest sister; I’ll bring you some tomorrow, and you shall know for yourself what a delight it is.”

We lay in bed that night the way we always did, our golden heads together, folded in each other’s embrace. Cheek to cheek, breast to breast. The way it was, every night. Nothing had changed. Everything had changed. I watched moonlight cast its gaze down upon Lizzie’s face, heavy with slumber. I traced the line of her jaw, the plumpness of her cheek, the powdery lashes and silken locks. I had tasted heaven, but it wasn’t enough. All those fruits, which I had so wantonly devoured, were a poor replacement, compared to what I desired most. But, that was something I could never have. That desire only led to ruin and death. It could never be.

The next day I rose with Lizzie as usual; we fetched the honey and milked the cows as usual; aired and cleaned the house, made cakes, churned butter, fed the chickens and did our sewing. But while she went about the chores with an open heart and a smile, I stumbled about languidly, as though I was sleepwalking. I felt sick. I longed for the night to come.

When the sun finally burned away we went down to the brook to fetch water. Now Lizzie moved sluggishly, while I leapt about like a flame. She filled the pitchers with haste, and hurried us back home.

“Come, Laura, we shouldn’t lag. No one else is out, even the squirrels and birds are fast asleep.”

“You go,” I said. “I need to catch my breath. Besides, it’s not that late yet, the wind is still warm and the dew hasn’t taken. Go, I’ll be with you in a minute.”

Yet for all my watching and listening, I didn’t spot a single elf — let alone the crowd that had tramped along the banks the day before. At length, Lizzie’s fretfulness grew overpowering.

“Oh, Laura, come! I can hear your elves whistling after me, but I dare not look. Let’s go, we shouldn’t loiter here a minute longer. It’s getting dark and clouds are gathering; I don’t want us to get lost on our way back.”

I scarcely heard what she was saying. But when she said she could hear the elven merchants, my ears began to ring. My limbs turned to stone. How could it be? Why couldn’t I see or hear them? Did that mean I could never buy more of that fruit? Was I to go through life without even the salve to ease the pain of the impossibility of my heart’s desire? Was I to be deaf and blind? Alone, untouched, unhappy, for all my remaining days?

I said nothing to Lizzie that evening. I trudged after her, not really seeing where I stepped, my pitcher dripping all the way. I crept into bed. I lay silent, watching Lizzie as she slept. When the anguished clawing in my breast became too much to bear, I sat up, my fists clenched, and — through gritted teeth — I wept. I wept over thwarted passion, my unfulfilled yearning, feeling as if my heart had gone itself asunder.

Day after day, night after night, Laura waited, listless, sullen — but in vain. She never again heard the elves’ cry, never saw them peddle their fruits along the bank. Her lovely hair grew thin and lost its shine. Her bright eyes turned dull and sunken, the dark circles under them growing ever larger and darker. She dwindled and decayed, and all I could do was watch.

One day she took the kernel stone, which she had saved from the fruits she ate, and planted it by the wall facing south. She nurtured it, wet the soil with her own tears — beautiful in its way — and watched for a sign of a waxing shoot, but there came none.

Her heart’s rot worsened. Laura no longer swept the floors, didn’t tend to the fowls or cows, never brought water from the brook. She didn’t eat, nor took walks with me about the heath. She only sat in the armchair in the chimney-nook, and stared at nothing. Her lips waned, her hair fell out, her arms thinned until they looked like twigs. She was turning into her own ghost.

I could not bear it. To watch her die a slow, wasting death, unable to help, unable to even share in her suffering. It was too much. Night and morning, I heard the elves’ cry, “Come buy! Come buy!” each time I came within an inch of giving in to their call. I longed to buy some fruit to comfort my sweet sister, to soothe her soul's gaping wound. I loved her so dearly. And yet, I did not love her quite enough to dare to buy the enchanted fruit. I feared what it may cost me, and recalled, every night, the grassless patch of dirt under which Jeanie lay. Instead of resting in a soft bed with her husband, she was lying, alone and in silence, in cold earth, dead with the first snows of crisp winter time.

Eventually, Laura’s illness progressed to the point where I expected Death to knock on our door any moment. I couldn’t afford to weigh my doubt for a day longer. I put a silver penny in my purse, kissed Laura, crossed the haunted furze heath, and at twilight, came to the brook and waited.

The elves saw me peeping, and ran up laughing and capering. They leered and scowled with their ugly, monstrous faces. They hugged and squeezed me, kissed and caressed my skirts. They raised their dishes, panniers and plates to my face, and cried: “Buy!”

I steeled myself. I remembered poor Jeanie, and treaded carefully. I tossed them the silver penny and held out my apron. I said:

“Good folk, give me much and many of your lovely fruits.”

The elves shook their heads. “Nay, come and sit with us; our feast is only just beginning.”

“Thank you,” I said, “but there is someone waiting at home for me, alone. If you shan’t sell me any of your fruits, please give me back the silver penny I paid you.”

Now the elves no longer kissed and smiled. Their cooing turned to grunts and snarls, and they looked to me more like a pack of howling beasts. They called me a conceited, cross-grained, and foolish girl.

I made to leave, run up the glen; but the moment I moved they lashed their tails, gripped and hustled me, and pressed me against the trunk of a quaking aspen. Before I knew what I was about, they had already sunk their claws into my skin, tore my gown, soiled my stockings, all the while hissing and barking and mocking. They pulled my hair and cocked my head back, and held me firmly against the hard woody trunk. Only when one of them cackled evilly in my face, a fat dripping fruit in his hand, did I realise what they meant to do to me.

The elf thrust the fig against my mouth, but I clenched my jaw and held my lips closed tight. My defiance agitated the beast men, and more of them flocked forth, to rub their fruits against my face and neck. They squeezed the flesh and dripped its juice all over me. Scratches of their claws burned me, nettles and briars they were. But though my lashes were damp with tears, I remained still and silent. In my heart, however, I laughed.

Their fruit no longer posed any danger to me, any temptation. I savoured the juice that syrupped all over my face, streaked my neck and ran down my bosom. I understood what Laura had craved so much. I understood, also, the longing in my own heart, which I had silenced for so long. For while I took no bite of the elves’ fruit, the thirst which they engendered could only be quenched one way. I imagined the sticky juice that ran down my cheeks was Laura’s. I pictured her nails were the claws that ripped my bodice open. I longed to taste the fruit of her mouth, to burn with her as one. I knew why Jeanie had sought the elven-men; and though her end was sad and painful, did that mean mine must be? I did not think so. I had Laura. And I had to save her. If I couldn’t bring her the elves’ fruits, I could at least offer their juice to her mouth — offer myself. If the only way for her to live was to devour me, so be it. I welcomed such a fate with utmost joy.

At last the evil elves grew tired of my resistance. They scurried away, kicked their fruit, tossed my coin back at me. They went their way, and I, on quivering knees, went mine. I sprang up the bank, across the heath, my penny bouncing and jingling in my purse, like bells ringing for a wedding; a promise of happiness to come. I ran, but it was not the fear of elven men that spurred me on. No — it was the warmth of my heart which guided my paces, though I was out of breath it urged me home with haste. And all the while I ran, inwardly I laughed and sang to the tune of the silver penny.

As I stumbled down the garden path, my shoulders shaking, I cried out, “Laura! Laura!” I received no reply. I ran up to the door and flung it open. “Laura!” The room was dark, a single candle’s light flickering in the corner. I entered. I looked about, and as my eyes accustomed themselves to the darkness of the room, I saw her. She was sitting in the armchair with her legs drawn up, her chin against her knees — like she used to when we were both little. When I stepped towards her, her eyes fluttered open, then grew wide, then turned fiery with fright.

“Lizzie, what happened to you?”

She took me by the hand and squeezed it, and the touch of her fingers upon my skin, and the loving, desperate look in her eyes washed away the fear and the cold. I smiled weakly.

“Did you miss me?” When she did not reply, only stared at me, confused, I said, “Come. Come and kiss me. Never you mind the bruises. Hug me, dear sister. Kiss me.”

“But — but you are covered in…”

I moved closer. My heart beat painfully hard; I felt it was going to beat right out of my chest! But I could not stop. I did not want to.

“Eat me. Drink me. Love me. Laura, take me, do with me as you please.” I put a trembling hand to her cheek, and ran the points of my fingers down the line of her jaw.

She started from her seat, flung her arms up, and pulled at her hair.

“Lizzie, Lizzie, have you gone mad?” she cried. ‘Have you really taken their fruit, for my sake?” I nodded. “Oh, merciful God! Lizzie, I don’t want you to suffer the same fate as mine! I would not wish it on anyone, least of all on you. I don’t want your light to dim, and your beauty to waste. Oh, God!”

“I don’t care,” I said. “I have braved the glen and suffered the torments of the elves for your sake. It was all for you. So take me. I want you to.”

“Lizzie, if I do — if we do — there will be no going back. Do you want to be ruined, forever?”

I shook my head. “To not do it, to live without your touch — that would be ruin.”

She embraced me and began to weep. Her eyes, that had been dry and dull for so many weeks, were made glittering and fresh by the tears, which fell like the rain, after a long summer drought. She shook — we both did — she shook and kissed and kissed me.

She licked the juices off of me, ran her ravenous lips and tongue over my burning flesh. She sucked and sucked and sucked me, and I began to lose myself to her. The dripping fruit of the elven men was nothing to it, nothing at all; I had never felt anything like it before. Then she bit into me, and I cried out in pain and pleasure. My legs gave in, and, her clinging to me tightly and hotly, we fell to the floor. Like vagrant young vines, our legs entwined. Our mouths came together, again and again. Laura sucked on my lip, then bit it, and I felt myself running like clear, sweet juice from a grape. Her mouth was dyed scarlet with it; she licked her lips and swallowed me. The sight drove me further out of my senses. My ragged breaths and frenzied sighs fuelled her hunger; she meant to devour me. I wanted her to do so.

Like into the velvet nap of a peach, she put her mouth to the soft curls between my legs, and bit and sucked and lapped. She clawed at my frock, my skin, my flesh, peeling me away layer by scorching layer. Her fingernails were the blade of her pen-knife. I writhed like a person possessed. I wrent her robe and pulled it off of her. She reached inside me, and drew out blood and water. She lay upon me, and moved against my thigh, our bodies growing slick. When she kissed me, my lips began to char, but instead of pulling away I leant deeper into our kiss. Laura sighed, and moved away, and we gazed into each other’s eyes for one long, breathless moment.

Her locks, which had grown ashen and lank, now streamed like the mane of a horse in mid gallop, and burned with the golden light of the rising sun. The sight of her beauty sent flames rippling through my veins. Fire began to scorch my insides. I needed her touch, I needed more, I could not be sated. I think she must have felt the same, for she gorged on me with renewed passion, sucking and tearing and lapping and cutting, with soul-consuming fervour.

My head grew light. My vision grew red, like watching through the crimson skin of a cherry. My whole body, and hers, and the entire room, were shrouded in red. Scarlet was pooling under me, viscid, dyeing my fair hair bloody.

She had opened me up, parted my flesh, shown me a freedom, a fire, a feast; more dazzling and beautiful than anything I could have imagined. Like a lightning bolt, she touched the heart of me, touched the raw and keen core of my flesh, and I came apart. An earthquake ran through my whole body, shattering my limbs, and I felt pleasure, pain, anguish, all of it in a whirl. There is nothing that can compare. Ruin of my body, damnation of my soul, they felt like such a small price for the miracle of this feeling.

For there is no love like a sister’s love, enduring even down a path that leads astray; falling and tottering down with you, even into the depths of oblivion.

Was it death, or was it life?

Or, perhaps, life out of death.

Appeared in Issue Spring '24

Nationality: Croatian

First Language(s): Serbo-Croatian

Second Language(s):

English

Das Land Steiermark

Supported by:

Comments on "Market of Delights"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login