Published June 29th, 2021

Review

by Andrea Färber

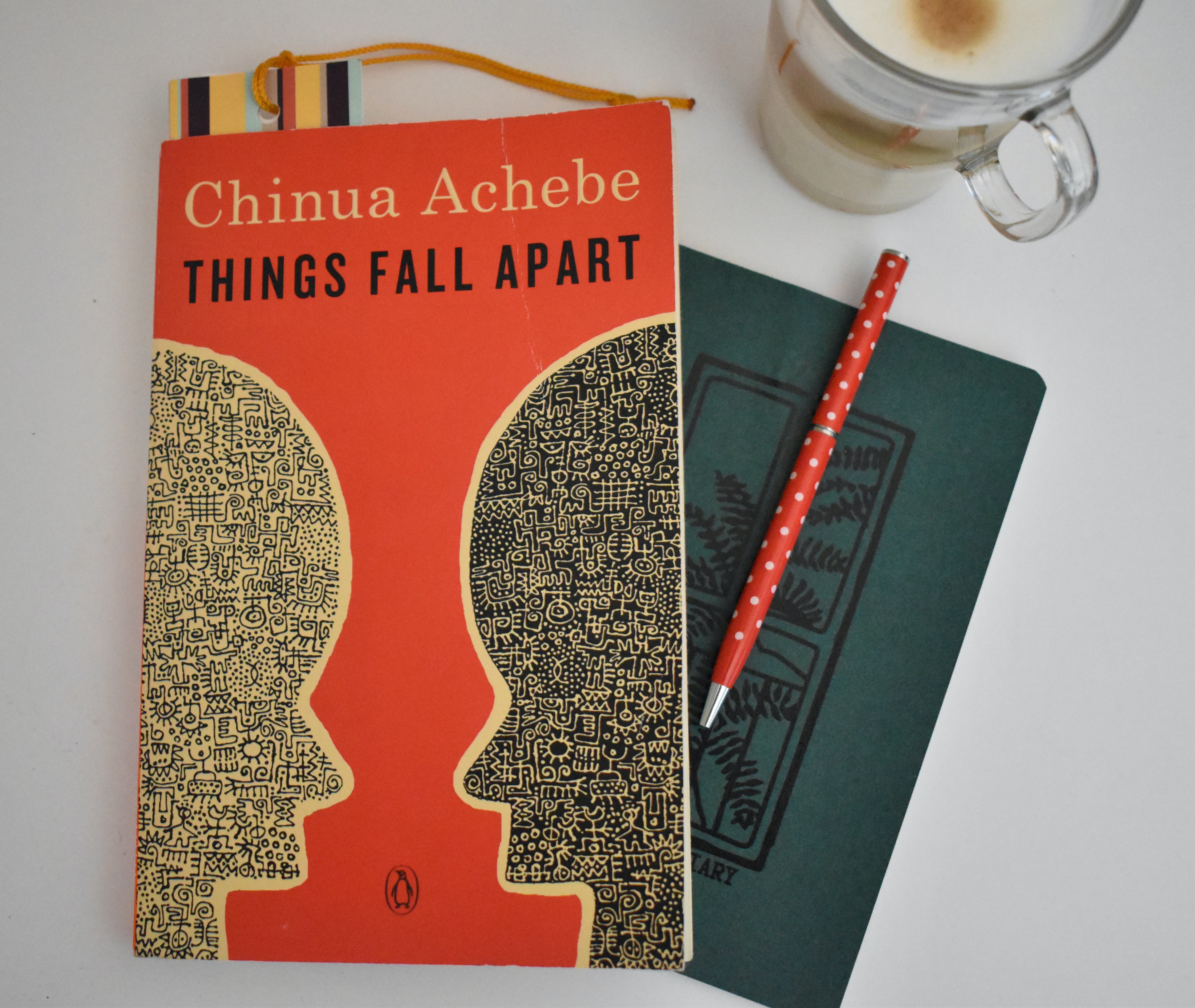

In Things Fall Apart (1958), one of the most prominent writers of African literature, Chinua Achebe, tells the story of Okonkwo. Readers find themselves in an environment of oral traditions, myths, and folktales while they are invited to reflect on the role of the colonizers as the contrasts in the story develop.

I am the type of person who prefers to have her books in neat conditions — no dog-eared pages, creased book spines or damaged book covers. My copy of Things Fall Apart, however, is damaged to no end. That is because if a story really sucks me in, I no longer have the patience to carefully turn the page and I take the book wherever I go until I’ve read it from cover to cover. It almost seems like a cliché for me to say this, as Things Fall Apart is hailed as one of the most important novels of history by many, if not the most important novel that has come out of African literature, but during my third time reading the novel in preparation for writing this review, I was as mesmerized by the story as I was during the first time.

For the uninitiated, Things Fall Apart was first published in 1958 by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, the first of three novels of his “African Trilogy”. It follows the story of Okonkwo, a villager and warrior living in the clan of Umuofia. In three parts, the book that is set at the end of the 19th century introduces the reader to the culture and practices of Okonkwo’s clan, before drawing to a close as the British start to infiltrate their lands, convert the villagers to Christianity and establish their own government, taking agency away from the locals.

Achebe, whose first language was Igbo, is one of the most prominent writers of African literature. Thus, he was often heavily criticized for choosing to write his novels in English, the language of his colonizers. Achebe defended his decision by stating in his essay “English and the African Writer” from 1965 that one has to differentiate between national literature and ethnic literature: “A national literature is one that takes the whole nation for a province, and has a realized or potential audience throughout its territory; in other words, a literature that is written in the national language. An ethnic literature is one that is available only to one ethnic group within the nation. If you take Nigeria as an example, the national literature, as I see it, is the literature written in English; and the ethnic literatures are in Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba, Effik, Edo, Ijaw, and so on.” (1997: 343)

Despite having been written in English, the conventions of Igbo oral tradition shine through in Things Fall Apart on many different levels. The narrative itself reflects Igbo oral tradition in the unique way that it has been written, and explicit mentions of the features of the language are also included:

“Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm-oil with which words are eaten.”

Furthermore, myths and folktales are a prominent part within the novel. They either get relayed by characters, such as when Okonkwo’s second wife tells her daughter Ezinma the tale of the tortoise who gets punished for its greed, or are explicitly told by the narrator to the reader, such as during the gathering of a village public trial that is headed by nine egwugwu (representations of the spirits of their ancestors). Traditional songs are interwoven into the story, and cultural proverbs traverse the text that would look out of place in any other English novel. Within the context of the setting, however, they add a new layer of authenticity that allows the reader to fully immerse oneself into the story.

Being fully immersed into this story is a necessity in order to be able to fully appreciate the pre-colonial setting and cultural practices, and Achebe does a thorough job mixing plot with an adequate amount of description in order for the reader to be able to follow along without the information being overbearing. The novel offers both insight into the life of the clan from Umuofia, teaching about farming practices and traditional celebrations, as well as offering a gripping plot that runs smoothly through it. Okonkwo and his family of three wives and several children build the core of the characters that gets expanded into friends, priests, and the entire village when depicting customs in detail.

Things Fall Apart also invites the Westernized reader to reflect. It teaches about practices such as abandoning twins in the evil forest, or killing people as tributes to the gods. Near the end of the book, the British take in the castaways and admonish the tribe for its customs. However, that does not make the colonializers the good guys. They wipe out entire villages. They hold hostages and torture them, hang them in the name of their government in their new home. Their practices are just as irrational to the indigenous, as the indigenous habits are irrational to them.

And by the end of the book, the words leave behind a bitter aftertaste that forces the reader to question what is right and what is wrong, and about the cruelty of colonization that, even in a mostly post-colonial world, we like to turn a blind eye too. The story of Okonkwo and his clan is as much educational and engaging as it is frustrating as the novel moves along, and it is rightfully a staple of classic literature.

Achebe, Chinua. 1997. “English and the African Writer.” Transition: The Anniversary Issue: Selections from Transition, 1961-1976 no. 75/76: pp. 342–9.

Nationality: Austrian

First Language(s): German

Second Language(s):

English,

Spanish,

Japanese

Supported by:

Comments on "“There is no story that is not true”: A Timeless Classic in Restless Times — A Review of "Things Fall Apart" by Chinua Achebe"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login