Published November 10th, 2025

Review

by Viviana De Cecco

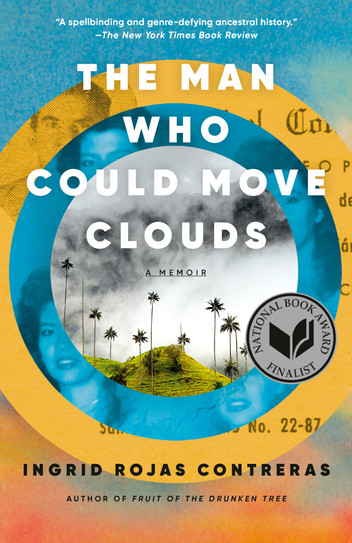

The Man Who Could Move Clouds (Doubleday, 2022) is much more than an autobiography. It explores universal themes such as family ties, identity, racism, colonialism, machismo, and feminism. Colombian writer Ingrid Rojas Contreras, who immigrated to the United States during the 1980s drug wars led by Pablo Escobar, tells a story that can be lighthearted one moment and moving the next. Her novel intertwines the past and the present, magic and reality, premonitory dreams, and visions of ghosts, reminiscent of the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez and Isabel Allende's The House of the Spirits.

Ingrid Rojas Contreras takes readers on a complex and fascinating journey into the soul of Colombia, a country ravaged by violence and death, as well as into the mysterious meanderings of her mind. Distressing and happier memories become symbols of the search for lost roots. After losing her memory in a bicycle accident when she was 23 years old, Ingrid questioned herself and her history. Thus, the story begins, a journey back in time to reconstruct the history of her family and an entire people, piece by piece.

As my memory returned, piece by piece, I grieved. If amnesia was weightlessness, then the opposite was true: every path taken, every word said, every knowledge discovered, every emotion lived — all of it — came back to me with a manifest weight. The narrowing of a life is gravity. Memory is burden. I mourned every ounce of memory returned. (Chapter 1 – The Secrets)

Ingrid was born in Bogotá, with family roots on her mother’s side in Ocaña, in the state of Santander, and belongs to the “mestizo” ethnic group, consisting of people with brown skin who are descendants of Spanish conquistadors’ violence against indigenous women in the 17th century. She describes herself as “a wound” (Chapter 1) to emphasize the terrible fate of the local populations.

In addition to being excluded from the white community because of her mixed race, life as a woman is difficult as well. Most importantly, she is not considered worthy of inheriting the family “gift,” the ability to heal people and see the dead, which is passed down from father to son. However, her grandfather, the curandero who inspired the book’s title, believes that his daughter — Ingrid’s mother — has the strength and determination to bear the burden of this uncomfortable legacy. It is certainly not easy to be seen by society as strange or even “cursed” because, according to tradition, all women who possess this gift will be afflicted by misfortune. When deaths and accidents begin to occur in the family, Ingrid reflects on what it means to take on such a “profession.”

Her grandfather has always seemed almost mythical to her. He is an indomitable man with a multifaceted character: part philosopher, part madman, part doctor, and part sorcerer. He may bring home an anaconda or a lynx, but he also listens to others and helps them with his herbs and the wisdom of the ancients. But what role does a curandero actually play? Can her mother truly see the dead and predict the future?

As a child, Ingrid watches people turn to her mother and grandfather for cures to physical and mental ailments. From this experience, she learns an important lesson: Words can work miracles, too. Everyone who crosses the threshold of her grandfather’s “office,” where he practices homeopathy to avoid being considered a fraud, has a story to tell. The curandero often becomes the keeper of secrets and confessions, understanding what advice and solutions to offer to alleviate the emotional pain afflicting all clients, regardless of class. His real task is to decipher the pain of others and convey the truth through symbols and rituals. When Ingrid reads tarot cards for her classmates, who turn to her for help, she realizes that providing answers to those in need is more difficult than it seems.

I dealt cards despairingly, for the first time, understanding the responsibility of divination. It wasn’t just about precision; it was about interpreting the language of grief and finding there is a sense of direction that had eluded the client. But violence was nonsense. What possible answer could there be in the face of it? That must have been why curanderos were often people who had survived illness, near-death accidents, loss. It took going into the abyss and returning to know how to open a path through wreckage. (Chapter 14 – Water)

She will soon have to deal with suffering, too. In 1988, Colombia became the setting for a war between drug traffickers and the government. A bloody incident forces her entire family to emigrate to Venezuela. 14-year-old Ingrid cannot forget the anguish of her terrible experiences. Although she leaves for the United States alone in subsequent years and moves to Chicago, she continues to bear the marks of her trauma on her body and mind. The appearance of her grandfather in a dream, asking to be exhumed, brings her back to her native country on a spiritual journey more than a physical one.

In the second part of the book, the author intertwines her experience with the story of her grandparents, who met between the civil war of 1948, called La Violencia, and the periods of peace when, amid rubble and death, hand-cranked gramophones began to play again to resume normal life. Thanks to the vivid descriptions, the reader feels as if they are walking through dusty, deserted streets in small villages where Ingrid’s grandfather stops with other street vendors in plazas to offer his healing services.

As the story unfolds, readers are transported to the most remote corners of Colombia, where the curandero encounters legends of magical lagoons populated by beautiful women who walk on water and guacas — secret treasures buried in caves that emit supernatural light. Ingrid finds it difficult to believe the stories her grandfather tells her. She is fascinated by the magical and legendary aspects of her homeland but is reluctant to accept that she is like her relatives for fear of being seen as different and an outcast. She even questions her own mother’s supernatural abilities despite her frequent complaints that no one believes her. Even before the accident, when her mother predicts something bad will happen to her, Ingrid doesn't believe her. It is only when they find themselves digging up her grandfather’s body that they reconcile. He is buried in one of the “miraculous” tombs scattered throughout the country, alongside men of science. Many people visit the cemetery in Bogotá to ask for a miracle.

However, for Ingrid, the real miracle her grandfather performed was appearing in the dreams of all the women in the family at the same time, reuniting them and bringing them serenity. After the exhumation and cremation, Ingrid spends a few days with her mother and other relatives. When she returns to the places of her childhood, she makes peace with her mother and herself. She also realizes that she can overcome what she calls “síndrome de supervivencia” or “survivor syndrome” (Chapter 18 – Four Women) on her path to freedom, self-acceptance, and hope for a more peaceful future. By writing this book, she makes peace with her pain and gives her people a voice, ensuring that their culture is not forgotten.

The histories and stories of a people are a mirror — they tell how and when and where and why a people lived. No matter the year or the hour, empire will always seek to destroy the mirrors in which it does not see itself. This is why the colonizing culture does not consider our stories passed down through memory to be a valid document; why they are deemed to be more dreams than history, just as our perceived realities are deemed to be fiction. This is the language in power. It has never been able to imagine anything outside itself. (Chapter 23 – The Mirror)

Nationality: Italian

First Language(s): Italian

Second Language(s):

English,

French,

Spanish

Supported by:

Comments on "The Language of Grief — A Review of Ingrid Rojas Contreras’ “The Man Who Could Move Clouds: A Memoir”"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login