Published August 4th, 2025

Review

by Sabyasachi Roy

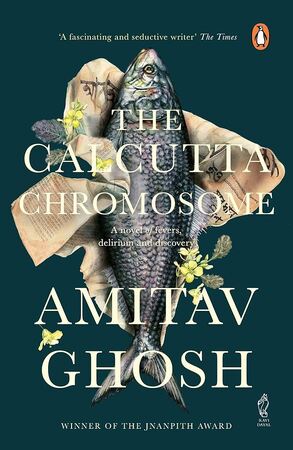

Let’s start with a small confession: I didn’t expect this book to be this weird. Or good. But mostly weird. The Calcutta Chromosome (first published 1996 by Picador) is that baffling thing you pick up thinking it’s going to be about colonial medicine and Victorian men with magnifying glasses, and five pages in you’re questioning if malaria is a metaphor, a weapon, or a sentient lifeform plotting your downfall. Amitav Ghosh does not hold your hand through any of this. He smirks and pushes you into the pool.

Set in a techno-future that’s dated in a 90s floppy-disk way (we're talking full-blown “data archiving” as plot device), the novel dances back and forth between a digitized New York and a ghosted, feverish Calcutta, both of which feel equally unstable. The narrative follows Antar, a loner working for a heavy research corporation, and his obsession with a mysterious missing file: Murugan. Who, you ask? That’s part of the game. Murugan is an amateur historian obsessed with Ronald Ross — the colonial-era scientist who discovered the mosquito's role in transmitting malaria. Murugan’s conspiracy theory? Ross didn’t solve malaria himself; he was led. By whom? A secret society of lab assistants, mystics, and lab-coated misfits manipulating science through ritual. Sure, why not?

This is not The Da Vinci Code. Thank God.

If you’re the kind of person who expects science fiction to be full of sleek glass buildings, testosterone, and AI girlfriends named Ava, you’re in for a small stroke. The Calcutta Chromosome doesn’t care for genre labels or your need for structural hygiene. It flirts with sci-fi, slinks through historical fiction, mutters things about metaphysics under its breath, and has a slightly unhinged relationship with horror — but a dusty, colonial horror. One that smells like antiseptic, has leeches in a jar, and probably speaks fluent Latin.

The brilliance — and occasionally, the headache — of this book lies in how it lets superstition and empirical science exist in the same airless laboratory. For instance, Ghosh doesn’t just question the myth of individual scientific genius; he dismantles it with the fervor of a man sick of dinner-party know-it-alls. Ronald Ross, the Nobel-winning guy you learned about in school, becomes a bumbling puppet in the hands of unnamed “subaltern” characters. These characters — mostly Indian, mostly invisible in history books — pull strings from the shadows using some ancient knowledge system that may or may not involve actual chromosome-swapping.

No, really. Immortality through ritualized malaria research. That’s where we are. Somewhere between H.P. Lovecraft and Nature magazine.

Ghosh is not interested in storytelling as a sequence. He wants echoes, fragments, unreliable narrators, and a timeline so scattered it probably resembles a Jackson Pollock painting if you squint hard enough. This isn’t a novel you read so much as one you map — badly. There’s Antar in the future, Murugan in the 90s, Ross in the 1890s, and a rotating door of peripheral characters who might or might not be reincarnated versions of each other. At one point, I was 80% sure two characters were the same person across time. By page 200, I was less sure I even existed.

But that’s the point, perhaps. Knowledge, identity, memory — they all blur. Ghosh seems to enjoy watching his readers spin. He doesn’t explain the mechanics of this secret science. He hints. He obscures. And like Murugan, you start connecting dots that may not exist, inventing meaning in the static. By the time you realize you’re part of the experiment, it’s too late.

A friend once told me, “Don’t read Ghosh if you’re sleepy.” Good advice.

One of the most subversive pleasures of The Calcutta Chromosome is how it rewrites colonial history as a bad conspiracy thriller — and I mean that in the best way. Western science, with its obsession for order, patenting, and discoverers, gets punked by Ghosh’s rogue cast of Indian lab assistants, nursemaids, and silent witnesses. They don’t need to write things down. They pass knowledge like a virus: orally, spiritually, sometimes telepathically. While British officers scribble into their journals, convinced they’re cracking the malaria code, the real players are behind them, swapping blood, reciting mantras, maybe time-traveling. It's like finding out your favorite science textbook was ghostwritten by a tantrik in disguise.

There’s something deeply satisfying about this inversion. Ghosh doesn’t just historicize the theft of indigenous knowledge; he flips it. The colonizers think they’re extracting secrets. But what if the secrets were leading them on a wild goose chase the whole time? What if the native subjects weren’t passive victims but god-level researchers playing a long con?

If you're expecting a neat ending where the timelines click into place and the big reveal happens with orchestral swell, you’re reading the wrong book. Ghosh is too slippery for that. The Calcutta Chromosome is deliberately unresolved, uninterested in explaining itself, and — let's face it — kind of rude in its refusal to be helpful.

And yet, the lack of closure is what gives it power. It lingers. The book lives somewhere at the edge of your rational mind, nudging it, whispering, “Are you sure you know how knowledge works?” It refuses to tell you whether the chromosome is a metaphor or miracle. It doesn’t explain why everyone is so obsessed with malaria (though, to be fair, it is a kind of ancient horror). And it certainly doesn’t let its characters emerge as anything so bourgeois as “main protagonists.”

What it does, and brilliantly, is make you question the borders we draw — between myth and science, memory and history, self and other. Ghosh’s colonial Calcutta is a fever-dream city where these lines warp, mutate, and loop back on themselves. It’s like the letter in the novel that says, “The young man has promised to reveal everything to me if I would but accompany him to his birthplace. Fortunately the place of which he spoke is not far from the location of my clinic. We are to leave tomorrow” (p. 133). Well! You are left there waiting eagerly for the answer. You finish the book more puzzled than enlightened, but somehow satisfied. Like a good haunting. Or a very polite possession.

Look, it’s not a page-turner. There are no romantic subplots (unless you count vague soul transference). No heroic scientists. No aha moments that explain everything. Yes, it’s messy by a degree, yes, it’s strange by some imagination, and yes, certainly, it’s full of contradictions. And yet it feels — how do I put this? — uncannily relevant. In an era obsessed with “data” and “breakthroughs,” when everyone wants to discover something and stick their name on it, Ghosh reminds us that knowledge doesn’t always arrive in lab reports. Sometimes it wears a sari, chants mantras, and swaps chromosomes in a back alley while the Nobel committee sips its tea.

Reading The Calcutta Chromosome is like trying to remember a dream you had when you were slightly feverish and maybe possessed. You know it mattered, but good luck explaining it to your friends. And that’s the kind of story I’d trust more than any headline.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bengali (Bangla)

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi

Listen to "Science Was a Ritual and the British Didn’t Notice — A Review of Amitav Ghosh's “The Calcutta Chromosome”":

Supported by:

Comments on "Science Was a Ritual and the British Didn’t Notice — A Review of Amitav Ghosh's “The Calcutta Chromosome”"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login