Published March 18th, 2024

Review

by Scott Ward

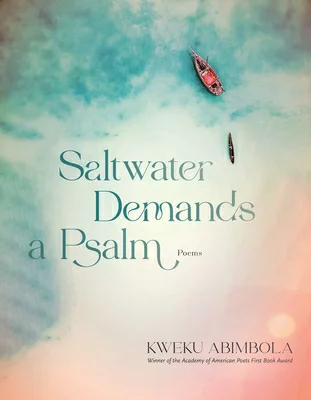

If you are a dedicated reader of American poetry, perhaps, like me, you sometimes find contemporary poems a bit predictable? The poetic lexicon seems confined, a regrettable fact since English is a vibrant language, promiscuous in its tendency to invent and adopt new words. Many poems seem intensely focused on the poet’s emotional life, another chapter in the poet’s earnest biography. If you find yourself hankering for poems that avoid reflexive habits of treatment and language and that offer the energy and surprise of an alternative cultural awareness, Kweku Abimbola’s Saltwater Demands a Psalm (Graywolf Press, 2023) offers just that. It is no wonder that Tyehimba Jess, a poet whose book Olio won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize, selected the volume for the 2022 Academy of American Poets First Book Award. The poems and the forest of symbols that surround them are sometimes strange but always delightful, charming, and compelling.

Abimbola was born in Gambia and counts Gambia, Sierra Leon, and Ghana as the places that formed his mind and culture. He earned an MFA from the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program. His poems meditate upon systemic violence against Blacks, climate change, colonization, West African cultural traditions, folk wisdom, the value of names, and the nature of symbols, in the wonderful Adinkra symbols of Ghanaian culture and in Abimbola’s employment of concrete poems. As the poet explains to James Morehead in an interview for Viewless Wings, “The visual element was really my attempt to decolonize language,” an impulse that is clear in the structure of Saltwater Demands a Psalm, as the poet weaves together his own diverse cultural resources with American culture and poetic conventions.

The first, and title poem, of the collection, “Saltwater Demands a Psalm,” establishes Ghanaian cultural values that will inform the speaker’s experience and the book’s themes, especially commitments to the land, the sea, and the family. The speaker and his friends have risen early, eager for a day’s work of fishing. Early sun on the groundswells shows a “silver snakeskin,” suggesting life and the renewal of life. The names of the boats help extend this tone of renewal, Good Luck, Big Catch, but they also add nuance to the tone through the name, Nyame Dua, an Akan phrase which means “God’s Tree,” adding a note of the sacred. Everything seems wholesome and stable; the tone is joyful and forward-looking. But the reader soon discovers that the fishermen’s work will not be productive as barges have come and “scraped the reefs clean,” spoiling the subsistence fishing. The barges are agents of corporations and colonialism that put profit before the welfare of the local people. The speaker asks his father if the water is dead:

He said, The water is only as dead as the bodies beneath,

and alive as the bodies above. He reached down

offering a palmful of saltwater; we both drank.

Swear to keep this balance.

After the detail of the barges’ destruction, the tone takes on a dismal cast. The forces of colonialism seem too imposing for local fishermen. The father’s saying counters that tone. He looks to the future, connecting the fish and the fishermen in the idea of a healthy natural life cycle. The contrast of death below and life above holds the two realms of natural and human in balance, but it also places the responsibility on the people, suggesting that to be alive, one must be responsible for the “bodies beneath.” Suddenly their talk becomes an intimate ritual as they imbibe the water. The religious quality of this communion recalls the Nyame Dua or “God’s Tree,” a symbol of divine protection. Then the father urges the son to make a promise: “Swear to keep this balance.” This promise also looks to the future, involving environmental common sense and a custodial relationship to nature, but the ritual, because it springs from the relationship, highlights in a vivid way the things that depend on caring for the fisheries: the relation of father and son, of people and work, of the extensions of family and community that work supports, of a proper place among the shadowed protection of God’s Tree. The oath is powerful because of the intimacy of the father-son relationship and because it is a means of seizing agency for their future.

Before the title page and the title poem, the reader encounters this Adinkra symbol:

This is the symbol denkyem or crocodile, which suggests cleverness and adaptability. The symbol adds yet another layer of significance to the title poem, allowing readers to understand the father’s ritual oath as emerging from ingrained cultural values. Therefore, the son promises to adhere to and maintain those values. This also communicates the culture’s notion of time in the poem: The cultural value of crocodilian adaptability emerges from the past, transmitted from father to son, is cultivated in the present by the son, and will come to the son’s aid in the future.

Readers will encounter many aspects of poetry that seem familiar at first glance; however, an attentive reading will often complicate the familiarity. This is true for Abimbola’s elegies, which are key to the structure of the collection. They are written for Black Americans who have suffered death as a result of systemic, institutionalized violence. “Efiada” is composed in remembrance of Tarika Kaye Wilson, who was killed in 2008 by a police officer during a raid on her home. She was holding her 1-year-old son, who was injured by the shot that killed his mother. Ms. Wilson was 26 years old. In the English tradition, elegies often lament, praise, and offer solace to the bereaved, and this poem begins in much the same way, “you’ll remember her / as an exemplary mother to six children,” and then the poem offers solace, but does so according to the conventions of the Ghanaian dirge, in its vision of a diasporic spiritual realm:

because that’s all you can find

in english, then you’ll forget

to remember. enough. she returns

endless, to Asamando: Asante Eden, the place

english cannot hold.

Asamando is the land of the spirits, where dwell the Nsamanfo, or ancestors; death, therefore, is a mere transition, a continuation of spiritual existence and relationships with kin. The dirge imagines Wilson returning there and resuming her relationships with those who came before her. There is a sense of mystery and intimacy in this afterlife which English cannot comprehend, “english” standing metonymically for English speakers and American culture. But now the elegy does something that Western elegies do not do. It swerves from its focus on the deceased and places it squarely upon the readers. It quotes from Akan dirge that is sung especially for mothers:

eno, nko nnya me akyire oo

eno, nko nnya me akyire oo, osiantan

ena awu agya me oo:

aa mene hwan na ewo ha yi.

it’s time you failed to translate,

failed to interpret.

Here the poem’s structure creates a complex and astonishing metaphor. Readers are commanded to fail to interpret, and they are put in a position, confronted with the Akan dirge, in which they can hardly do otherwise. The dirge communicates the emotions and human responses appropriate to the death of a human being, but readers cannot access those responses. They must look up the words and learn a bit of a new language, to re-examine the experience of tragedy, its emotional importance, its psychological burden, its moral imperatives. The figure thus places readers in a position of reassessing their response to the death of a human being, the thoughts they think, the words they choose. Rather than offering readers “a safe space,” the poem forces them to take a hard look at their own heart and mind; in doing so, the poem offers an exercise for readers to recover something of the humanity of the deceased mother and, as a result, a bit of their own.

The book is structured around seven elegies similar to the one for Ms. Wilson. Important to these sections is the Adinkra symbol of the sankofa:

The sankofa bird looks backward and holds an egg in its beak. The figure suggests the enrichment that comes from looking backward as a person moves forward in life. It is associated with an Akan proverb which translates to, “It is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.” Each of the seven sequences ends with a magnificent concrete poem representing the sankofa that Abimbola creates in honor of the deceased, composed entirely of names. The bird perches on a short twig that is the name of the person honored. The outline of the bird, its tail feathers and wings are all made of the names of other Black people who have died in a similar manner. The realization is horrifying. And yet, the sankofa fetches for us what is left behind. It carries its egg, its little emblem of life and what it has gleaned from the past, into the future. It carries the memory of the dead, our sorrow, our hope. These poems and their cultural perspectives show the vitality of the Ghanaian elegiac tradition. These are poems that do not merely honor the dead, they resurrect them. The poems recover for the reader what is at risk of being left behind. They summon the dead by name, calling their spirits to return to the present, because there is both honor and value in doing so.

Kweku Abimbola has created an outstanding collection of poems. The energy, emotion, and psychological complexity the poems generate is fascinating. But beyond the poetic complexity that will engage readers is the fact that the work emerges from a poetic perception and a culture that is deeply human, a feature that animates the poems and compels readers.

Supported by: