Published January 19th, 2026

Review

by Amritesh Mukherjee

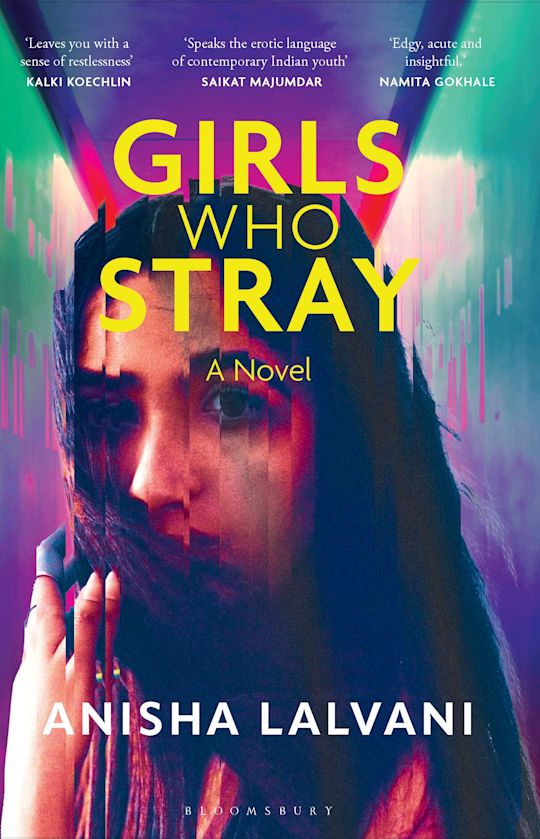

In a heavily gendered and surveilled society, how do you protect yourself? How do you find yourself? How do you reclaim yourself? Anisha Lalvani’s Girls Who Stray (Bloomsbury India, 2024) is the story of a society seen through the eyes of an unnamed girl. It’s intimate, it’s sweeping, but it’s authentic, much like our protagonist.

Girls Who Stray is a novel of straying, and straying, and straying again.

A strays from expectation. She returns from an unremarkable British education with nothing but debt; no plan, no future visible from where she stands. She strays through Delhi — through its gated communities and slums, its party circuits and construction sites — wandering without destination. She strays into danger: a property developer’s bed, an online escort business, the grim aftermath of a double murder. She strays from family — divorced parents, an ailing grandfather. She strays from herself, or toward herself, or discovers there was never a fixed self to stray from. Lalvani’s story refuses to moralize about any of it. Straying here is neither liberation nor ruin. There is no redemption arc here, no “lesson learned.”

The world feels a large, infinitely large, quick place, the people set in their ambitions, marching ahead with certainty to fulfil well-analysed dreams; and me, a step askew, with my head in the clouds. Bewildered, thinking vague half-thoughts through half-words and phrases that lead one to the other. (p. 99)

Anisha Lalvani’s debut is many things at once, refusing any singular definition. It’s a coming-of-age tale without any redemption arcs, a thriller without catharsis, a feminist text without easy solidarity, a love letter to Delhi as well as a hate letter to the city. It’s about urban spaces that promise women freedom and deliver policing at every stage. It’s about the capitalism that builds gated communities and the poverty that sleeps beneath metro pillars, about the general apathy toward suffering that allows both to coexist on the same street.

A witnesses Delhi, and Delhi witnesses her. She drifts through the capital’s strata — upscale cafés to metro stations, party circuits lit in neon to alleys with broken streetlights. The city of the India Shining billboards is also the city of limitless poverty. Delhi is a malevolent organism, a city that runs on inequality normalized to the extent of invisibility. The poor build the roads the rich drive on. The guards protect gates they’ll never pass through as guests.

... behind the blingy facade, I sense to my bone the outdated oldness of the city, the loose cement mixed with water, the makeshift corrugated iron sheets falling on top of filth beneath the metro pillars, tarpaulin tied in every corner, buildings in a perpetual state of repair lined with bamboo poles, cratered potholes everywhere, dried ghutka splatter, backs of broken bus stops housing the blankets of neighbourhood beggars. Children with no hands, women with no hair and men with no eyes, with outstretched hands and nasal pleas at every traffic signal. (p. 45)

This is also the city that teaches women their place through assault and aftermath. The Nirbhaya protests form a critical part of the novel, that brutal reminder of how rape culture works. What the rapists said — that she shouldn’t have been out at night, that she invited what happened — was exactly what the nation has been saying to its daughters for generations. That mobility is transgression. That freedom is provocation. That a woman moving through public space at night has already committed the crime for which rape becomes punishment.

After all, a jewel more precious than a diamond, if thrown to the streets, will naturally be ravaged by dogs. (p. 156)

The city is one kind of prison. Family is another. Every night, she returns to a family fractured beyond repair. Divorced parents living in separate cities, a father who plods through days at a loss for words, an ailing grandfather, a mother whose existence has forever rhymed with absence. After all, parents are not the adults who guide you into adulthood but ordinary people crushed by their own compromises and failures. The apartment her father bought is everything new construction promises — modern, aspirational — while being none of it, a holding cell where disappointment resides.

The turning point comes in a London hotel room when A wakes to find 500 pounds left by a one-night fling. She takes the money, spends it on things she’s wanted but couldn’t afford. She calls him, jokingly, her “first client in the escort business.” But that experience helps her recognize what her body can do — command desire, extract value from men who want access to her. She experiments with this online, controlling men from behind a screen. When she becomes involved with a Delhi property developer — obscenely wealthy — the same mechanics apply. He gives her money, escape, and a reprieve from her suffocating family. She gives him access, complicity, the satisfaction of possession. The book refuses to judge her or pretend there are clean choices in a system built on exploitation.

And this refusal to judge or indict persists. A makes astonishingly bad decisions — returning to dangerous streets, entering violent relationships — and the novel never pretends these are good choices. But they are her choices. When assaulted near Lodhi Gardens, she returns days later to the same spot. “Because I must. Because it is mine too, to walk on.” (p. 176) She spray-paints advertisements at midnight, parties until dawn, loiters in cafés, roams streets, asserting her presence in spaces built to exclude her. It’s the complicated, often self-destructive act of claiming space in a world that would prefer you stay put.

And so the woman must wait at the threshold, as women do, as women have done, for aeons gone and aeons still to come. (p. 151)

The novel’s structure mirrors its subject. Lalvani’s novel is as fragmented as its protagonist. The story spirals — here observing Delhi’s material inequalities, there veering into a fever-dream about technological futures, snapping back to A’s body in the present tense, her choices, her guilt everywhere. It’s how A experiences the world: through fragments, through observations piling up without coalescing into action, through numbness that makes everything feel equally urgent and equally distant, through days that stretch endlessly and days that vanish in a second.

Lalvani refuses the fantasy of the perfect feminist heroine. A is imperfect, trapped in the contradictions of her own privilege. She’s aware enough to see inequality — the protestors at Jantar Mantar, the invisible labor force sustaining Delhi’s wealthy enclaves — but too mired in her own crisis to act on that awareness. She feels solidarity but cannot join, understands injustice but cannot fight it. The book shows a young Indian woman being free in all its unglamorous reality. Making terrible choices, hitting rock bottom in a metro toilet, bleeding through her clothes, drunk and stumbling.

“They don’t like it, a woman on the loose going just where she pleases, doing just as she wants.” (p. 224)

The book captures the zeitgeist of our times: the psychological precarity of a generation caught between the promises of modern India and the ruins those promises leave behind. A is a mirror held up to the messy, unspoken realities of urban womanhood, where agency and vulnerability coexist, where freedom is accompanied by constant fear. In the end, the straying is the desperate human hunger to find purpose in purposelessness, direction in directionlessness.

Girls Who Stray is a novel of straying, and straying, and straying again. Because in a country that still believes good girls should stay put, the act of moving — however aimlessly, however dangerously — remains its own form of freedom.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bangla

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi

Supported by:

Comments on "A Woman’s Life, Out of Line — A Review of “Girls Who Stray” by Anisha Lalvani"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login