Published January 5th, 2026

Review

by Anushree Nande

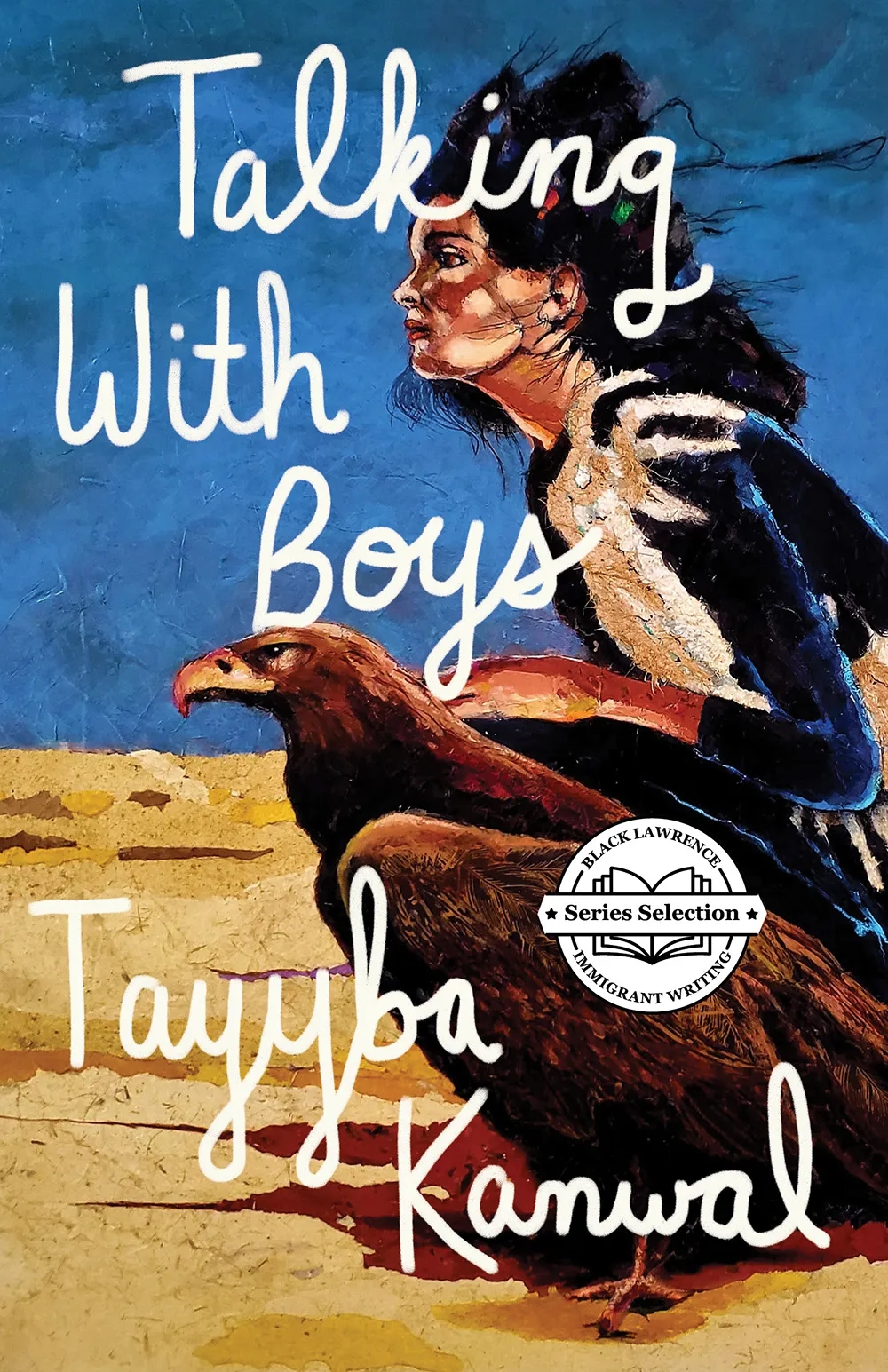

Tayyba Kanwal is a Pakistani-American writer and Literary Director at Inprint. In her debut short story collection Talking With Boys (Black Lawrence Press, Immigrant Writing Series, published January 6, 2026), she gives a voice to Pakistani and Pakistani-American women, navigating a plurality of experiences from cultural impositions over familial challenges to economic upheavals.

***

“Your sister escaped her husband’s home to meet her old love at the guava tree of their childhood… That night her three-year-old daughter, playing in a corner of her parents’ bedchamber, tripped over her mother's severed braid still entwined with her mirrored ribbons. It had been sliced off cleanly, to shame her. At sunrise, the same farm hands who had observed the tryst by the guava tree discovered most of the rest of your sister pieced into a gunnysack caught in some reeds downstream from the village. They never found her head.” (from “Little Mother,” p. 109)

Over 50 years ago in a Punjabi village in Pakistan, Tayyba Kanwal’s mother witnessed the murder of an uncle’s wife, an “honour” killing by her own brothers. In her debut short story collection, Talking With Boys, the Inprint Literary Director gives life to the ghost of that aunt whom she never met. Along with her aunt are many others who get a voice in their own story. They are offered that all-important choice, the agency for alternate possibilities without losing what makes them them, without destroying their cultural heritage or completely severing ties with their family, lineage, religion, and community. And at times, this choice also involves a chance for the still-living women to take their revenge, often in surprising ways.

Knowing everything that we do about the author’s narrative intentions, it makes sense that most protagonists are Pakistani and Pakistani-American women. Whether it’s an adolescent girl on the brink of womanhood who wishes she and her cousin could remain little girls forever, and, when it isn’t possible, takes drastic measures (not the kind you’d think); a housewife who discovers infinite reserves of fortitude and ability within her when her husband is stricken with a sudden strange ailment; an indifferent wife of a rich man who is simultaneously a fiercely loving mother whose “glow could be said to be manufactured… but the incandescence in her eyes was her own, her soul still untired” (“The Girl Who Ran,” p. 23), who helps a lost young woman get what she really wants, even as she safeguards her only son’s future; a mute girl who grows up to forge her own path and happiness against the odds; a secretly pregnant, unmarried young woman who marries her late sister’s husband so that she can protect her “ferocious little imp” (“Little Mother,” p. 108) of a niece and also give her new in-laws an heir.

These women are of varied ages and backgrounds who live between three locations in Pakistan, Dubai, and Houston, through the decades between 1950 and 2020. As they navigate a multitude of familial and societal expectations, bear generational burdens, and traverse external and internal emotional landscapes, the author deftly weaves in larger discussions about the immigrant struggle faced by any diaspora community. And yet, the focus never leaves the women: their hopes, dreams, and needs, rarely voiced aloud, mostly nurtured in secret and seasoned with wishful thinking; the options available to them and their resultant decisions, even if the potential consequences are often brutal and unforgiving; the sacrifices and the watchful patience essential to eventual freedom, which, too, wears many different hats.

This is an interlinked collection — something that becomes evident about three stories in (I kept a running list of the various character overlaps) — and the beauty of this manner of intersection of lives and destinies is not only in the way it mimics real life, which anyone living in a South Asian community can attest to, but also in the way this tapestry showcases both shared patterns of culture and language while pointing to the individual specificity present within the multi-layered lives Pakistani-origin women have always lived. Lives that can be subject to change, on their own terms. The author also slips in instances of magic realism (and in the case of “Mailee and the Saint of Horses” a full-blown fable-like story) that never feel shoehorned. They exist simply as another piece of the complex terrain of identity she’s traversing and attempting to pin down, as part of her attempt to push back against the false singularity of Pakistani culture as an “oppressive system to escape at all costs.”1

.jpg)

At this point, you may wonder, correctly, why the collection is named Talking With Boys. The title story is number four out of fifteen, but even before you read it — “Baba had never needed to tell me, but I knew that, like other girls in our circles, I wasn’t supposed to talk to boys. None of our mothers had male acquaintances” (“Talking With Boys,” p. 57) — it starts to become clear why the author chose that reference, and why, many times, it stands in as a searing metaphor, despite being a seemingly innocuous action.

The opening story, “The Girl Who Ran,” and the one that closes the collection, titled simply “Bungalow,” are clever contrasts to bookend the collection. Both lead characters are young women in Houston. The former is a rebellious recent high school graduate itching to escape a future that involves being sent to Pakistan to live with her paternal grandmother and her “little mother” (father’s legal second wife), whom she, her mother, and older brothers have very recently been told about; the latter a Mathematics professor — raised mostly by a single mother who was completely out of her depth as a widow in a foreign land and has since returned to Pakistan — who wants a place to call her own (“a home I could learn, a space I could fashion” — “Bungalow,” p. 170) and decides on a decrepit bungalow against the advice of her estate agent.

Kanwal’s writing is assured and direct, with unexpected humour and wit laced in, but she isn’t afraid of an oblique turn of phrase when needed. And to her credit, the subtler or more open-ended insights aren’t the kind that try too hard or make you strain so much that the reading of the stories stops feeling enjoyable.

Talking with Boys is about endings and new beginnings and everything in between. It is, to borrow from the dedication, about “the steel in the silk.” And as her characters tell us:

“If your heart is racing for us girls, tell it we survived, and in the end, that’s what matters. We adjusted. One does when one has to.” (“Telling Tales,” p. 137)

1 Wording taken from the promotion blurb.

Disclaimer: The author has received an advanced reader copy.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Marathi

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi,

German,

Spanish,

Sanskrit

Supported by:

Comments on "A Plurality of Women’s Lives — A Review of “Talking With Boys” by Tayyba Kanwal"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login