Published February 17th, 2025

Profile

by Viviana De Cecco

Brought as a slave to the United States from Africa at a young age, Phillis Wheatley went on to become the first African-American poet to be published. She has left an important legacy behind, however, her story also needs to be reflected critically. This review aims to celebrate her literary achievement while also highlighting the potential that was missed.

Phillis Wheatley lived in the 18th century, a tumultuous historical period in which reason and science became the focus of philosophical and literary thought. The American Revolution led to independence from British rule and marked the beginning of the struggle against slavery.

Surely, when she was deported as a slave at the age of seven to an unknown land, a thousand miles from the African village where she was born, she could not have imagined that she would become the first poet of African-American literature.

Torn from her roots against her will, she showed undeniable talent in writing. Therefore, we cannot view her literary ascent solely in a positive light, nor can we consider her a non-controversial role model for today’s African-American or global generations. Beyond the façade of her success, her story proves the difference between mere apparent freedom and true freedom of thought and action.

We do not know for certain whether Phillis was born in Senegal or Gambia in 1753, but we can imagine a ship full of slaves sailing from the shores of Africa to the port of Boston in 1761. On board were enslaved men chained together, women and children left naked, cold and without food, subjected to the most cruel beatings and harassment. Among these innocent beings, stolen from their villages and families by ruthless slave traders, was a seven-year-old girl, alone and defenseless in the face of this horror. Like all the other captives, she did not understand or speak the language of her captors.

By some miracle, she survived this hellish journey, and when she disembarked from the ship, she was sold at auction to a white couple, John and Susan Wheatley, who bought her as a house slave. Mrs. Susan, who was aging and needed a slave younger than those she already had, sensed that that frail and shy child would be no trouble. She likely believed that her submissive nature would allow her to exert both physical and mental control over that slave girl.

When Susan, who was a woman respected in the city for her culture and fashionable salon, noticed the child’s vivid intelligence, she allowed her to attend the lessons she personally taught her daughters. The girl quickly learned English, both written and spoken, and managed to read the Bible within a few months. Mary, the Wheatley’s daughter, was appointed by her mother as her tutor and taught her subjects such as Latin, history, geography, astronomy, and religion.

So the nameless child was baptized and became Phillis Wheatley. The first name was the name of the slave ship on which she had arrived from Africa, and the second was the surname of her owners, who at that point were already becoming owners not only of her body but also of her mind.

For Phillis, learning to read and write in a century where slaves were not allowed to educate themselves, and owners were advised to keep them in ignorance, was undoubtedly a significant achievement. Understanding the words and the culture of those around her possibly gave her a sense of comfort in a society where she was deemed inferior.

However, Wheatley’s teachings cannot be considered solely an act of generosity. Her owners educated her so that she would think like the white population. It was much easier to uproot the cultural background from the mind of a developing child than that of a more mature woman.

Thanks to her qualities, Phillis was regarded as superior and different to other slaves and spared from performing their laborious tasks. She found herself suddenly thrown into the Wheatleys’ parlors, sipping tea with the other ladies and girls of Boston’s good society. Her intelligence was transformed into a curious phenomenon that Mrs. Susan showcased in public as if at a vanity fair.

Behind the mask of kindness worn by her mistress, there lurked a self-satisfaction in her power as a white woman who had managed to exert absolute control over her slave. During social gatherings, other girls enjoyed listening to Phillis’ tales of the places she had visited. Although she attended social events with her master’s family, she would never truly be their equal.

She likely adapted into a false sense of belonging to the entourage of whites as she also learned to distinguish herself from other Black people but also to know her own place, which was not the same as the white people she was surrounded by. In doing so, Phillis aligned herself with Mrs. Wheatley, a white woman who considered herself superior to a black woman and whose false moralism did not help her emancipate herself from a feminist perspective.

In 1722, when intellectuals in Boston read Phillis’ verses, they questioned her abilities, accusing her of not being the author. Phillis defended herself in court and willingly chose not to conceal her intelligence, convincing all those skeptical men that her poems were the product of her brilliant mind. In this regard, it was undoubtedly a victory against the mindset of the Enlightenment, which, despite placing reason at the center to uproot superstitions and unfounded beliefs, was still plagued by retrogressive thoughts that deemed women, especially Black women, as beings devoid of any intellectual capacity.

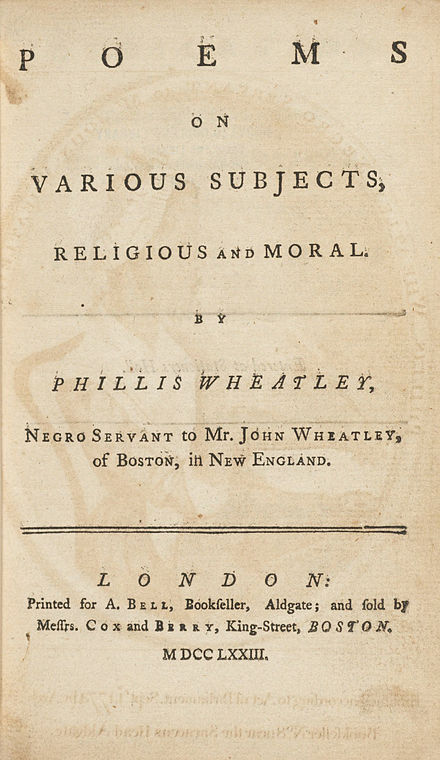

Phillis emerged from the ordeal with her head held high, but all the publishers in Boston refused to publish her poems. The Wheatleys did not give up, and in 1773, Nathaniel took their ward to London, where a friend of his mother, the Countess of Huntingdon, funded the publication of the young slave’s first book. Her writing skills brought her fame, but in reality, her condition remained that of a woman who was submitted to the values and mindset of a culture that sought to chain her in every aspect.

Phillis was 21 years old when her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious And Moral, became a success in both Europe and the United States, receiving favorable reviews and praise from politicians such as George Washington and the admiral and privateer John Paul Jones, considered the father of the American Navy, as well as writers such as Voltaire.

Her poems bear only few traces of her childhood in her African village, nor do they depict the lives of the Black slaves who worked in the Wheatley household. Phillis never describes how the other servants lived, nor does she openly denounce the terrible abuses inflicted upon them by the masters.

In the poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” she speaks of her deportation, but even then, she goes on to liken her own people to Cain, the archetypal sinner, and thanks the Lord for saving her from a land where she would have had no future. This can be seen as erasing and disowning her origins, which contributed to Phillis becoming doubly enslaved to her masters.

Using a formal language that adhered to 18th-century standards of harmony, perfection, and structured composition, she addresses themes of morality, the Christian religion, art, imagination, and study. She often invokes the Muses, the ancient protectors of the arts, while many verses praise God as the savior who led her to salvation.

In the case of the poem “To the University of Cambridge,” it is emblematic to note how Phillis underscores the importance of study and knowledge, which she claimed has rescued her from a world of obscure ignorance. Those who study must know how to leverage what she defines as a “privilege,” in order to elevate their spirits above the ideologies that whites must eradicate to guide Blacks along the path they deem “right.”

Phillis wrote mostly elegies, typical compositions of classical literature, in which she praises influential figures of her time, including reverends, gentlemen, army captains, and some ladies she had met in England.

In the poem “A Farewell to America,” written on the occasion of her journey to London, one senses the heartbroken spirit with which Phillis leaves that land she now considers her new homeland.

After the exceptional success of her book, when she returned to Boston, the Wheatleys granted her freedom. However, she chose to live with them until the death of John Wheatley. Later, after marrying John Peters, a free Black man working as a grocer, two of her three children died at a young age. Following this tragic event, her husband was imprisoned for debts, and Phillis was forced to seek employment again as a domestic worker, living in poverty until 1784 when she died at the age of 31, along with her third child, in a small boarding house in Boston. Shortly before her death, she wrote a second book of poems, which did not find a publisher.

Her dramatic story can teach us that true freedom must lead to self-assertion to express one’s ideas without being influenced by a dominant culture.

Sources

https://poets.org/poet/phillis-wheatley

https://www.masshist.org/features/endofslavery/wheatley

https://interestingliterature.com/2022/03/best-phillis-wheatley-poems/

Smith, Eleanor. “Phillis Wheatley: A Black Perspective.” The Journal of Negro Education 43, no. 3 (1974): 401–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/2966531

Nationality: Italian

First Language(s): Italian

Second Language(s):

English,

French,

Spanish

Supported by:

Comments on "Phillis Wheatley — the First Published Afro-American Poet"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login