Published September 1st, 2025

Profile

by Agnes Fodor

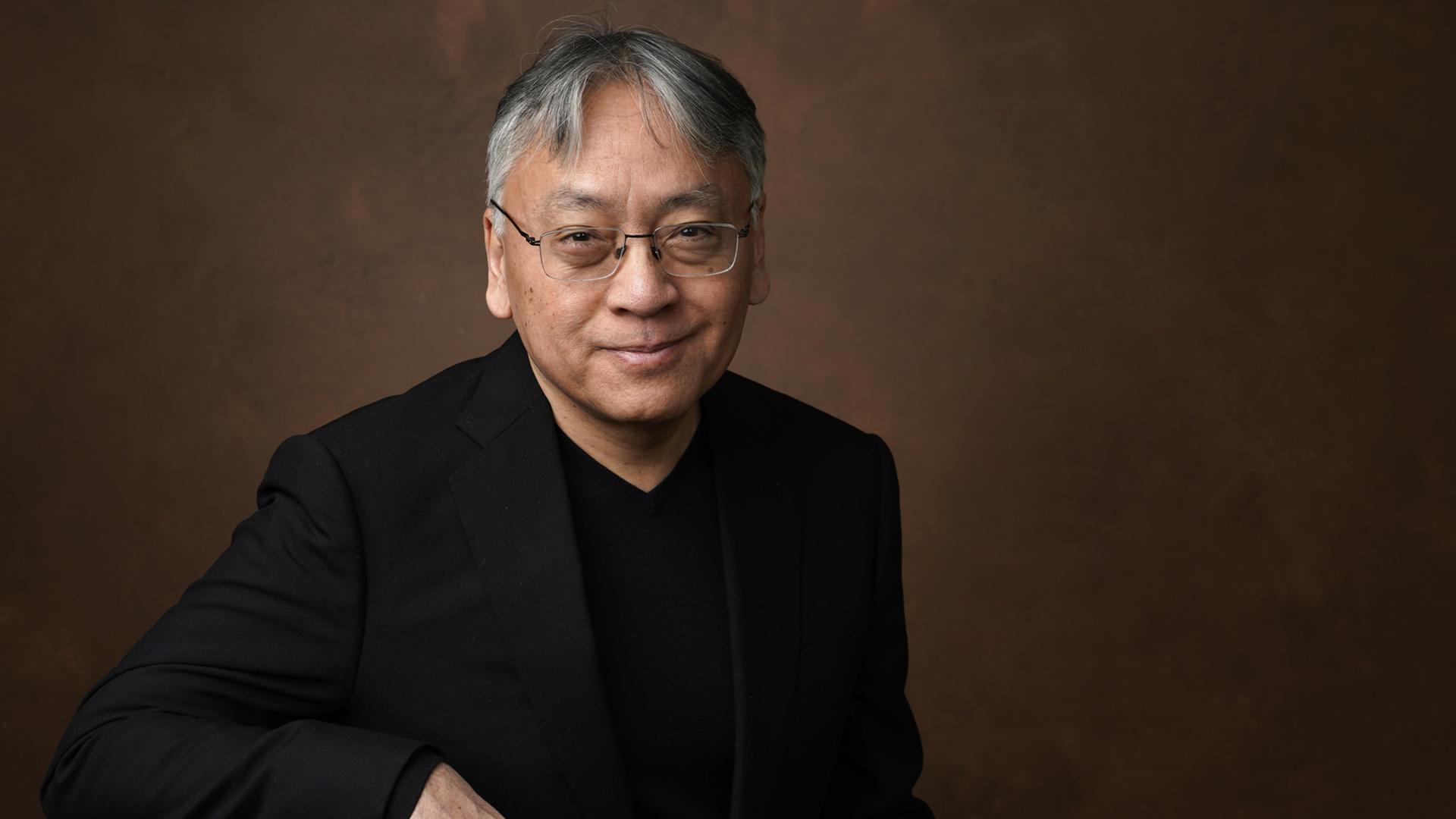

Having won some of the most prestigious literary prizes, the now 70-year-old Kazuo Ishiguro never fails to be his truest self: not quite British, not quite Japanese — or rather both, all at once — a confident and intuitive commander of a unique literary voice. He is on a constant quest for morality and the meaning of the human experience; he twists and investigates insoluble paradoxes, and reaches conclusions most readers probably don't see coming.

Let's be young again, if only for the weekend

Let's be fools again, let's fall in at the deep end

Let's do once more

All those things we did before-from The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain

lyrics written by Kazuo Ishiguro, composed by Jim Tomlinson, sung by Stacey Kent

It all might look simple at first, but trying to untangle the “Kazuo Ishiguro effect” will leave one perplexed. He is apparently prolific at cutting scones. His wife, Lorna, is equally prolific at making delicious and hot coffee. We know these are important facts for the former was reported by Literary Hub, the latter by The Guardian. Ishiguro and Lorna’s impeccably mannered British match must have been made in heaven indeed as it has been rolling on for a good 39 years.

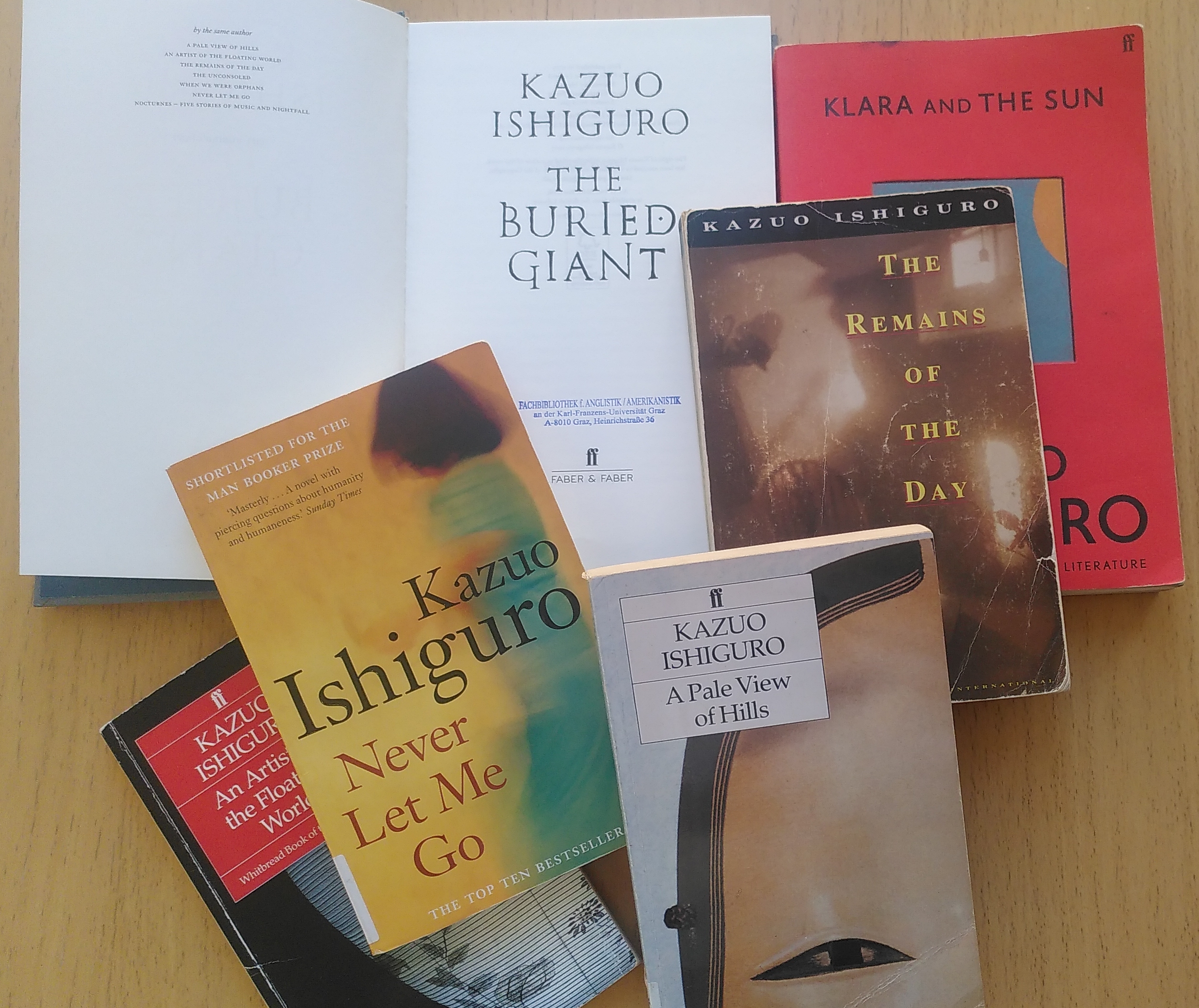

Ishiguro released his first book, A Pale View of Hills (Faber and Faber), in 1982 at the mere age of 27. His success — one could conclude — unfolded seemingly like a dream, for after getting his Creative Writing MA thesis published in Faber and Faber’s Introductions 7: Stories by New Writers (1981), a collection dedicated to upcoming British novelists, he was offered a £ 1.000 advance to expand it into a novel. A year later, he was featured in Granta’s Best Young British Novelists as the youngest on the list. For his second novel, An Artist of the Floating World (1986, Faber and Faber), he was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1986, which he proceeded to win for his third one, The Remains of the Day (1989, Faber and Faber), in 1989 at the age of 34. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017 (at the age of 62) — just one year following his personal hero, Bob Dylan. His screenplay of Living (2022, adapted from Kurosawa’s film, Ikiru) was nominated for the Academy Awards.

There’s just one question to be asked then:

What would all this do to the self?

Many of Ishiguro’s career decisions have shown solicitous attentiveness and have looked intently unconventional. After graduating from Kent University (where he’d studied literature and philosophy), he started working at a homeless shelter in London, where he also met his later-to-be wife, a young social worker called Lorna MacDougall. This amalgamation of experiences — a thrust into the reality of inequality and hardships, and an unfiltered life partner with a blunt taste for genuine criticism (amidst reluctant editors fearing to touch his work following his sweeping of awards) — would certainly be highly formative to anyone.

It might be no wonder then that he has clearly gravitated towards a few reoccurring themes and consequently reoccurring characters too, modern addendums to commedia dell'arte (although in his case tragedia dell’arte might be more suitable). This brings us to predominantly the questionable, ambiguous character whose crimes might not be harrowing enough to be cast out as a pariah but make accepting them inescapably hard. Underdogs of society the world long gave up on, from the morally questionable protagonist of An Artist of the Floating World to the star-crossed (or rather star-cursed?) lovers of Never Let Me Go (2005, Faber and Faber). All this presented in Ishiguro’s much beloved first-person narrative with the effect of “great emotional force” as The Swedish Academy concluded. First-person narration is also the form Ishiguro ties back to his early songwriting, his original “big passion,” the art form he “really believed in” and that he interprets now as an early apprenticeship before starting on fiction at all.

Ishiguro’s imperturbable mind is rooted in translingualism — a superpower that must at least be partially accountable for his uniqueness. He was born in Nagasaki, Japan, but moved to the UK in 1960, when he was only 5 years old. Consequently, he grew up in England but in a Japanese household. He is clearly happy to take risks and stroll off the beaten path — even though he is also a prominent defender of artistic repetition in his belief of gradual perfection of the same idea. His recurring themes often entail memory, guilt and the inextricability of human existence. These are not only subtly underlying traits in his works but also interests he often and openly discusses in interviews.

Famously, and in contrast to the idea of the genius brewing works for sometimes decades — often as proof of intellectual supremacy — he wrote the first draft of The Remains of the Day through a blistering process he called the “Crash,” something his fans can read about in detail on the website of the Booker Prizes. This process encompassed four weeks of secluded and obsessive writing time (which wouldn’t have been possible, of course, without his wife, Lorna, who took over his share of the chores for the time being) — an approach that brought him overwhelming success.

Although one needs to be a genius to pull off such a move so flawlessly — and recklessly — his success debunks the pretentious myth of the creative process, causing it to fall from its illusionary pedestal and thus unveil its pragmatic nature for the grand public. Ishiguro in this regard is certainly rather practical than superior. The man who worked as a grouse beater for the Queen Mother at Balmoral Castle in 1973 and packed baby food to save up money for a North American hitchhike trip to get a record deal as a musician (which he didn’t) could hardly be snobbish. Similarly, having complex, equal parts emotional and intellectual properties, he is not afraid of sprinkling humour over anything and everything while also moulding our heart dough dexterously. From the time he played a joke on a journalist who came to interview him (he acted as though he was the mere butler of his wife, Lorna) to opening cookery books on random pages and pointing at random phrases to collect potential book titles, he’s not afraid of appearing what he is: a human at play. He also claims there had been four years of an “audition process” of “sucking up to” the jazz singer Stacey Kent and befriending her before being able to write lyrics for her.

In his fiction, his austerely carved characters rarely get what they truly desire. If anything, they rather deal with loss: Axl and Beatrice have lost their memories in The Buried Giant (2015, Faber and Faber), the cast of Never Let Me Go has no control over their lives, in A Pale View of Hills Etsuko’s daughter died of suicide. Ryder — the pianist superstar of The Unconsoled (1995, Faber and Faber), Ishiguro’s most divisive novel — is unclear about what he wants and loses out on almost everything.

Craving to be a musician but ending up being the best at literature instead holds some of the absurdity Ishiguro’s books also often contain. With an array of jobs that never actively directed him towards being a novelist but ending up being one nonetheless, he’s been just as much off his desired path as his characters. “Being a novelist has been a good second choice,” he jokes in a Nobel Prize interview. As a teenager, he fell for music and — although he declares himself to be a competent musician (he grew up being a soloist in a church choir, and wrote songs inspired by Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Toni Mitchell as a teenager) — music, his first and biggest art-love, has never quite happened for him. Has he trailed off-track and found success or has he always been treading the wrong path finding the true one by mere luck? This is that one, true Ishiguro-esque paradox.

There is one thing, however, he talks about at least just as much as music itself: his family. A partner of a lifetime and a writer daughter, he loves diminishing everything else. It’s a thought easy to tie back to his view on the collaborative nature of music and screen writing as opposed to being a novelist: He wrote the script of Living (2022) specifically for Bill Nighy; a process he declared being very good for him for he can otherwise get “very monomaniacal and egotistical” when writing novels.

In The Guardian’s 20th anniversary interview of Never Let Me Go, Ishiguro expresses some concerns about his literary significance. As he says, not having been appreciated for his style nor for diving into injustices of the world, he’s always been regarded as a writer evoking tempestuous emotions: an effect he seemingly cannot quite make peace with for his fear of AI learning emotional manipulation very well – and very fast. He sounds truly concerned about his compliance. His latest novel, Klara and the Sun (2021, Faber and Faber), deals with the idea of artificial friends and shows the true depth of his anxiety. It’s understandable then that Stacey Kent, upon asking him to write lyrics for her, had one request only: a tiny bit of hope. Ishiguro shared the story at a Southbank Centre event with much amusement while also declaring he’d take it away as something to consider in his day job as well. Who would say then it’s a wonder he seems to bet on family, scones and humour rather than on One’s Glorious Importance?

There’s only one last question to be asked:

Losing that one big dream. What would that do to the self?

Want to read more about Kazoo Ishiguro's narrative works? Check out these tinted reviews of The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go!

Sources

https://lithub.com/kazuo-ishiguro-on-song-lyrics-scones-and-the-life-he-could-have-had/

https://achievement.org/achiever/kazuo-ishiguro/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p02sftcy

https://the-talks.com/interview/kazuo-ishiguro/

https://www.bookbrowse.com/biographies/index.cfm/author_number/477/kazuo-ishiguro#biography

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/20/kazuo-ishiguro-klara-and-the-sun-interview

https://www.newyorker.com/tag/kazuo-ishiguro

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2017/summary/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqDUstHYx4Q&t=3s&pp=ygUca2F6dW8gaXNoaWd1cm8gbm9iZWwgbGVjdHVyZQ%3D%3D

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Y3ItM5AQZs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6GJ7mrqo9nQ

https://www.bookbrowse.com/author_interviews/full/index.cfm/author_number/477/kazuo-ishiguro

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/authors/kazuo-ishiguro

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/kazuo-ishiguro-qa

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YwaewfvyZug&t=10s&pp=ygUaa2F6dW8gaXNoaWd1cm8gZG9jdW1lbnRhcnk%3D

Nationality: Hungarian

First Language(s): Hungarian

Second Language(s):

English,

German

Listen to "One’s Glorious Unimportance — A Very Ishiguro Paradox":

Supported by:

Comments on "One’s Glorious Unimportance — A Very Ishiguro Paradox"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login