Published February 16th, 2026

Profile

by Sabyasachi Roy

Some authors settle. They find their comfort zone and never leave. Jhumpa Lahiri never got that memo. She started writing in English, became a star, then decided: Nope, not enough — let’s go all in with Italian, a language she wasn’t even born into. Like moving houses not just across town but across continents, with no forwarding address. Who does that? Lahiri does.

But let’s rewind.

London, 1967. Bengali parents who probably wanted a neat little immigrant life, maybe a doctor-daughter story. Instead, they got a writer. She didn’t stay long in London — soon the family packed for the U.S., Rhode Island to be precise. So yes, Jhumpa Lahiri, Pulitzer Prize winner, literary darling, was raised on New England cobblestones, clam chowder nearby, and the low-level ache of immigrant dislocation.

Here’s the kicker: She was “strictly forbidden” to speak any language other than Bengali until age four (“Jhumpa Lahiri: A Writer Without a Real Language,” Hindustan Times, 2014). Imagine that. A household policed by language. English outside, Bengali inside, and a kid stuck in between. It sounds like a set-up for identity crisis bingo: guilt, exile, awkward dinner table silences. But it also gave her a vocabulary of double-vision. She’s been translating herself ever since.

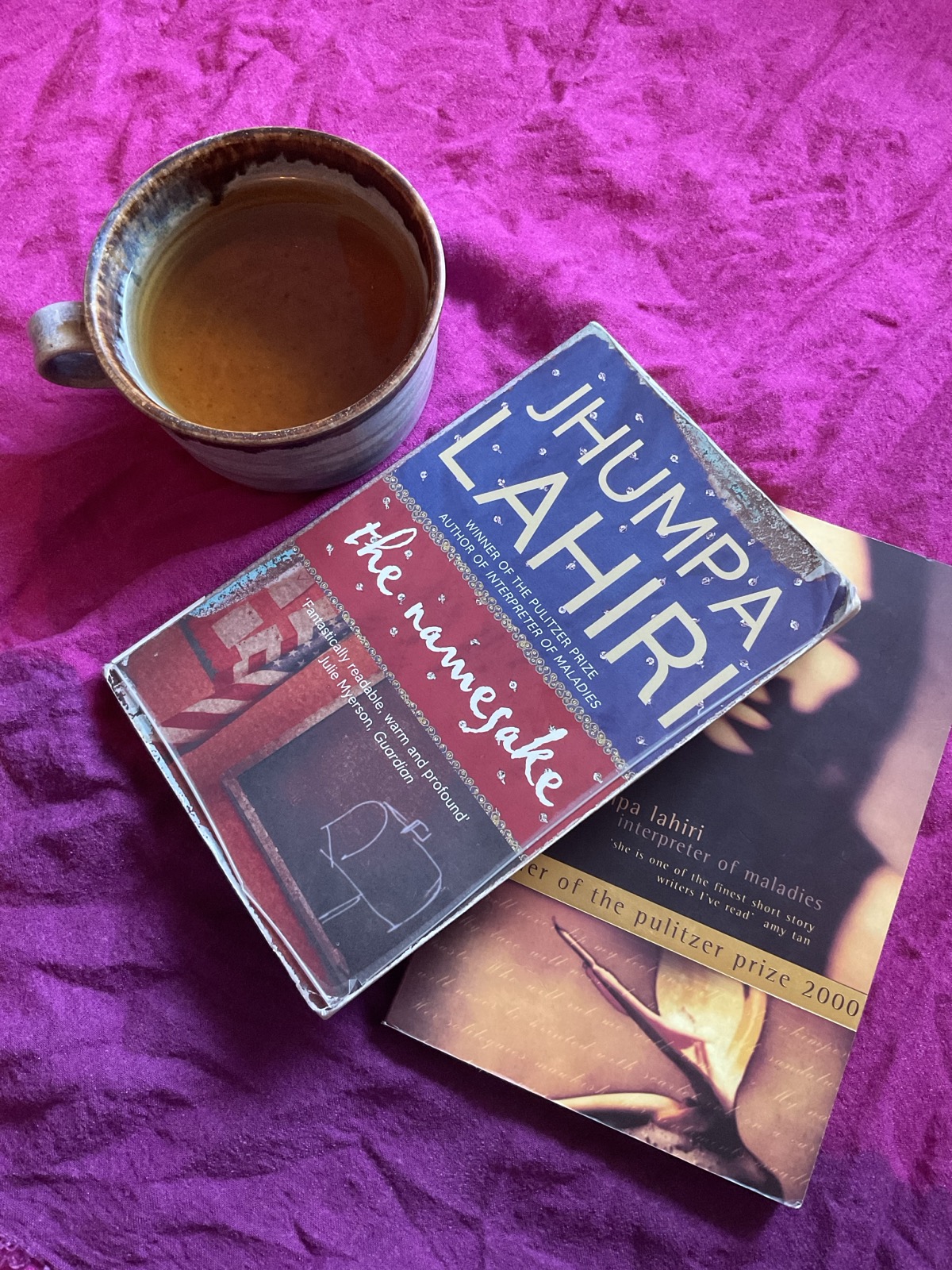

You know those writers who take ten years to publish a debut and then no one reads it? Lahiri wasn’t one of them. Her debut wasn’t supposed to blow up like that. Interpreter of Maladies (Houghton Mifflin, 1999). Out of nowhere — boom — Pulitzer. The book landed like someone pulled the fire alarm in every English department. Suddenly every syllabus, every book club aunt, was waving it around. These short, razor-clean stories about Bengali families just trying to survive New Jersey living rooms. They were everywhere, like that one brand of hummus you can’t escape in grocery aisles. Professors handed them out. Book clubs dissected them. Your neighbor probably pretended to have read them.

It’s unfair, really. Most writers crawl uphill for decades. She walked in and set up camp at the summit.

But don’t confuse her success with flash. Her prose isn’t pyrotechnic. It’s closer to surgical: clean, understated, and quietly devastating. She’ll describe a kitchen chair and you’ll feel like your childhood just broke in half.

Lahiri has always been filed under that big messy drawer labeled “immigrant writing.” South Asian American, hyphen-hyphen-hyphen. She didn’t ask for it. She didn’t exactly reject it either. She bristled, you could tell. Yes, she wrote about Bengalis in the U.S. Yes, about cultural static, the grind of in-betweenness. But no — there was more under the hood. She wasn’t your neatly labeled diversity slot. The marketing machine wanted a mascot; she wanted to be a writer.

Take The Namesake (Mariner, 2003). It’s about Gogol Ganguli (yes, named after the Russian writer; yes, the parents thought it was a good idea). A novel about names, identities, how you carry other people’s mistakes in your passport. Hollywood adapted it, and suddenly Lahiri’s stories were on the big screen. She became a brand. Which, if you read her essays, you realize she’s deeply suspicious of.

Lahiri also did the respectable circuit — degrees from Boston University, fellowships, the whole MFA ladder. She’s taught at Princeton, at Barnard, at the usual literary ivory towers. But if you hear her talk about it, you get the sense she’s never fully at ease with the “professor” identity (see “Jhumpa Lahiri Returns to Barnard as a Professor,” Columbia News, 2023). She’s allergic to pedestals. She’d rather vanish into language than preside over a classroom of wide-eyed undergrads.

Here’s the wild part. Around 2012, at the height of her American literary fame, Lahiri jumped ship (see “‘The Tragedy of Going Back:’ Jhumpa Lahiri on Her Work as a Translator,” Tobi’s Desk, 2018). She moved to Rome. Not for gelato, not for the Colosseum selfies — she moved to live inside Italian. She started writing in Italian. No English safety net. Just full immersion, like a swimmer burning the boats behind her.

Her memoir In Other Words (original title: In altre parole published in 2015 by Guanda) was the first fruit. Written in Italian, translated into English (not by her). It reads like a confession of someone cheating on their mother tongue. English had made her famous, Bengali had made her, but Italian was where she felt reborn. Talk about betrayal — or liberation.

And she kept going off-script. She wrote a novel in Italian first — Dove mi trovo (Guanda, 2018). Then, re-wrote it in English as Whereabouts (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021). Who even does that? Translating yourself, like smuggling your own luggage across customs. Rewriting every sentence so it doesn’t collapse at the checkpoint. Audacity, or just obsession. Maybe both. Few authors even try. Lahiri made it her whole life.

What does Lahiri even sound like? Hard to pin down. Thin, almost chilly on the page. She doesn’t hurry. Words trimmed close, like someone cutting hair with kitchen scissors. In English, the stories feel like she’s slicing something open with a scalpel — quiet, clean, a little unnerving. Switch to Italian and it gets even starker, like stone with the shine rubbed off. She avoids fluff the way some people avoid small talk. Where Amitav Ghosh piles everything in — maps, storms, history lessons — she strips it bare. No flood of facts. Just air, pauses, silence. And you’re left staring at the gap, wondering if you’re supposed to fill it or just sit there and squirm.

And her characters? Often lonely. Stranded between cultures, between choices, between languages. A man hosting tourists in Interpreter of Maladies. A second-generation kid juggling two names. A solitary narrator wandering Roman streets. These are not grand heroes. They are people in the liminal, the in-between. Which is to say, they are us.

Because Lahiri refuses to be fixed. Immigrant writer? Sure, but also Italian stylist. English short story master? Yes, but also translator, essayist, self-exile. She is the rare writer who made reinvention her signature. And in an era when everyone clings to brand identity, she slips labels like snakeskin.

She shows us that language is not a given. It’s a choice. A burden. A wound. A gift. All at once.

Reading Jhumpa Lahiri sometimes feels like looking into a mirror you didn’t ask for. The clean lines, the restraint, the silence — they throw your own dislocations back at you. You realize home is not geography. It’s not even language. It’s the endless act of translating yourself, again and again, into whatever words are available.

Not comfortable. Not cozy. But honest. And that’s Lahiri.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bengali (Bangla)

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi

Supported by:

Comments on "Jhumpa Lahiri — The Writer Who Changed Her Own Tongue"

You can't comment because your account is not activated. Please check your email inbox.