Published September 29th, 2025

Profile

by Sabyasachi Roy

Do you know any authors who just exist? You nod along while they publish books and receive accolades. Then we have Amitav Ghosh. With a pen so keen it could cut across colonial disinterest like butter, he does not merely exist; he is practically conjuring worlds and making you look at things you might prefer to ignore. He is more than just a significant figure for an Indian writer, with Bengali as mother tongue, particularly one who writes in English; he is essentially a tectonic shift.

Ghosh was born in 1956 in Calcutta, which is now Kolkata since history, like a good novel, always changes names. His early years were filled with a lot of activity. Imagine having a passport full of recollections from growing up in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and India. This geographical flexibility is weaved into his stories, so it is not just some interesting trivia for a book jacket. It makes sense that his characters are frequently lost, traveling across continents or oceans in quest of home — or perhaps learning that home is a notion that is far more fluid than any physical location. He studied at the Doon School in Dehradun, earned a history degree from St. Stephen’s College in 1976, followed it with a sociology master’s at the Delhi School of Economics in 1978, and then flew to Oxford for a PhD in social anthropology. A fiction writer and social anthropologist? Talk about a killer combo.

There’s something both exasperating and addictive about reading Amitav Ghosh. He’s the kind of writer who will send you down a Google rabbit hole about 19th-century shipbuilding in Calcutta when all you wanted was a nice, tidy novel. You begin with the hope of a story. You end up cross-referencing Chinese opium policy and Mongolian script variations. And oddly enough, you’re not mad about it.

Ghosh is, let’s say, academically overqualified. But what’s more annoying (and impressive) is that he doesn’t wield this like a blunt instrument. He sneaks it in. A sentence will start like it’s just going to describe a mango tree, and before you know it, you’ve got half a lecture on botany, trade routes, and the migration history of a fruit. This is not a complaint.

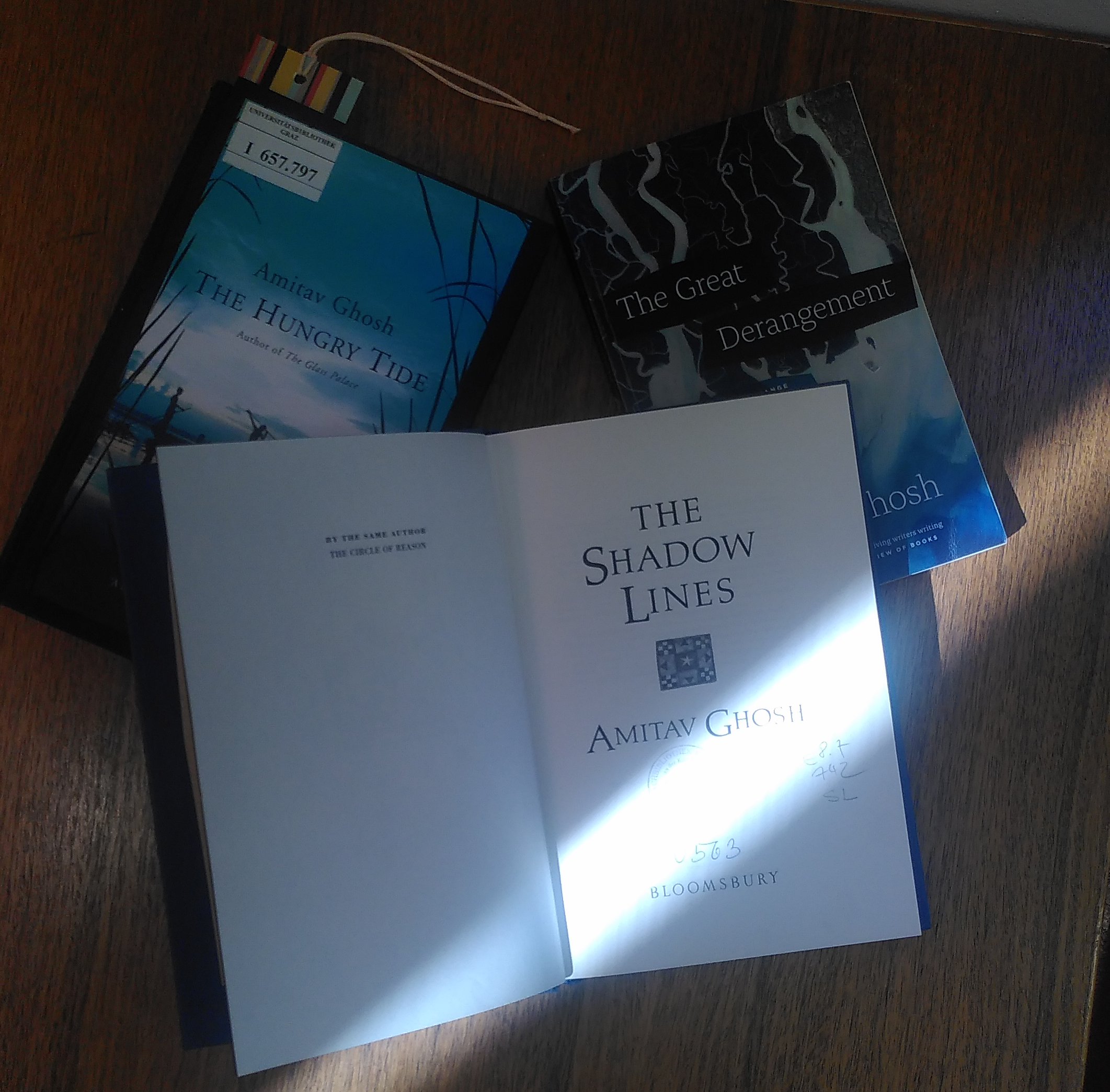

He began in the 1980s — post-Emergency India, Cold War still puffing along, before the literary world OD’d on autofiction. And there comes Ghosh, fresh-faced and suspiciously well-researched, writing The Circle of Reason (1986), which promptly ignored every neat rule about how a novel was supposed to behave. This was not drawing-room realism. This was maximalist, border-hopping, multilingual chaos. And somehow, it worked.

Then came The Shadow Lines (1988). Now this one is tricky. People often mistake it for a quiet, middle-class coming-of-age novel. And then, BAM — partition riots, imaginary geographies, and a sort of time-collapse that would make Christopher Nolan sweat. It’s one of those books that pretends to be about memory and ends up being about nationhood and the lies we tell ourselves. Very chill.

And then there’s the big one: the Ibis Trilogy. Sea of Poppies (2008), River of Smoke (2011), Flood of Fire (2015) — three massive tomes that chart the opium trade, colonial greed, indenture, revolution, and about seven languages’ worth of slang. If you thought this was going to be a quiet story about a ship, you’re adorable. These books are loud, crowded, and relentlessly curious. Characters speak in Bengali, Bhojpuri, pidgin English, bits of Cantonese, and whatever other dialects the empire vomited into existence. It’s like a literary Babel tower — but make it 19th-century and humid.

Now, some people say Ghosh is too encyclopedic. That the books read like historical compendiums with plotlines stapled in. Which, okay, fair. But here’s the thing — he knows. You can feel him messing with structure, pulling the seams apart on purpose. It’s like he’s telling you: “Yes, yes, I could write a linear narrative about a man who finds himself in a small town with a metaphorical past. But why do that when I can recreate the linguistic texture of colonial Mauritius?”

Let’s not pretend he’s only writing historical fiction. Ghosh saw climate collapse coming way before most writers stopped obsessing over dinner parties. The Hungry Tide (2004) and Gun Island (2019) are two books that, on the surface, look like they’re about dolphins and Venetian myths. What they’re really doing is pointing a giant finger at ecological disaster and saying, “Hey, maybe we should panic a little more.” But instead of yelling, he lures you in with story — then drops the panic when you’re too deep to leave. Kind of like being invited to a beach picnic and realizing halfway through that the sand is sinking.

What’s especially strange (and kind of fantastic) is that Ghosh is not obsessed with protagonists. Characters in his novels tend to float in and out. They don’t always “grow” in the Western-novel sense. Some of them vanish. Some of them reappear in another book, in another role, like Ghosh is just shuffling cards mid-game and daring you to keep up. And if you do? The payoff’s pretty great.

Here’s a personal confession: I once tried to read In an Antique Land (1992) on a train journey. Big mistake. I missed my stop, forgot my water bottle, and ended up halfway to another state. It was part travelogue, part memoir, part medieval Egyptian tax record. Which sounds awful — but trust me, it wasn’t. It felt like Ghosh whispering, “See? Even the footnotes matter.” And he’s right. They do.

He’s also grumpy in the best way. His nonfiction voice, especially in The Great Derangement (2016), is one of barely-concealed fury. Not the hot-take Twitter kind — more like a long, slow simmer from someone who’s watched governments and literary culture sleepwalk into disaster. He’s not subtle when he’s mad, and it’s sort of refreshing. At least someone with a brain is yelling.

If there’s a theme to all of Ghosh’s work, it’s that history isn’t over, and language never sits still. Borders don’t hold, time bends, and colonial hangovers are not going away just because your newsfeed did. He writes like someone who believes that fiction is the last remaining tool to make sense of all this chaos. Or at least to throw a few smart questions at it.

Is he always readable? No. Is he sometimes exhausting? Absolutely. But he’s never lazy. There’s a kind of rigorous, furious attention in his prose that makes most “well-crafted” novels look like IKEA furniture. You know the ones — smooth, functional, emotionally hollow. Ghosh, bless him, is not that.

What makes Ghosh unique? It is his voice, not the accolades or the sheer amount of his work. Thoughtful and frequently poetic, it manages to cut through the language of academia with a charming bluntness. He always goes deeper and connects strands that most of us would not even notice in his writing, which is characterized by an intense curiosity. Even though he taught at Harvard and Columbia, he may occasionally use colloquialism to remind you that he is not a stuffy professor. He is the guy at the bar who can talk about climate change after telling you a compelling story about the illicit trade in opium and somehow make it sound like the most conversational exchange in the world. He provokes thought, evokes emotions, and occasionally makes you question whether we are all dooming ourselves. However, he accomplishes it with such literary elegance that you hardly mind being awakened. He is one of those exceptional storytellers with an unwavering conscience. And we should all be grateful for it.

So if you’re picking up Amitav Ghosh for the first time, here’s a tip: Forget your genre expectations. Pack snacks. Bring a notebook. And if you find yourself suddenly wondering how saltpeter affected 19th-century Bengal agriculture, don’t panic. You’re just where he wants you.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bengali (Bangla)

Second Language(s):

English,

Hindi

Listen to "Amitav Ghosh — The Historian Who Forgot to Stay in His Lane":

Supported by:

Comments on "Amitav Ghosh — The Historian Who Forgot to Stay in His Lane"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login