Published March 3rd, 2025

Other

by Susi Peter

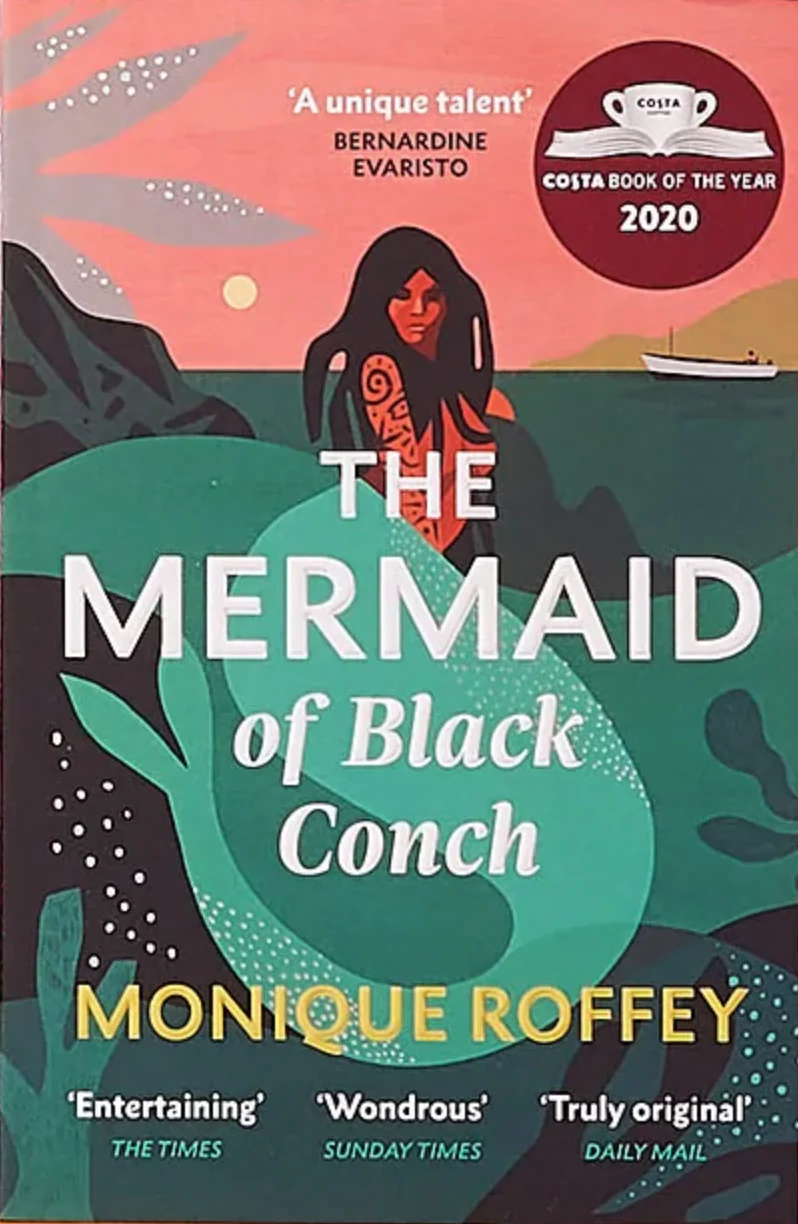

Our view of languages is shaped by a Eurocentric perspective that we are taught from an early age. Our author, Susanne Peter, reflects on how her perception of languages has changed with time and on the role postcolonial literature plays in this. On the example of Monique Roffey's The Mermaid of Black Conch, she shows the continuities of colonialism through the use of language and illustrates how essential language is to finding one's own identity.

I am sitting in my room, headphones on and my walkman plays a tape my brother recorded on repeat. I took a few CDs from his room and covered the floor with the booklets. Next to them, a dictionary. German – English, English – German. My aim is to translate the lyrics of the songs he recorded for me. I finally want to understand the text of the music that moves me so deeply.

At this point, I had just started to learn English in school. So far, I had read the songs’ translations in Bravo, a German magazine for teenagers that featured some lyrics every week, or I had to rely on what my brother told me a song was about. Both always felt like a big revelation to me. However, Bravo rarely featured songs that I actually liked, and it turned out that my brother used this opportunity to make fun of me: “Wish you were here” wasn’t a song about cleaning the floor. As a seven-year-old, I didn’t question that this wouldn’t be a good topic for a song.

What I learned in school was Standard British English (and, when we discussed the US or US literature, Standard American English). I wasn’t aware of any other Englishes for a very long time. I didn’t travel much as a kid, I watched TV in German — everything on German TV or in my small town cinema was dubbed. So, I only encountered English in school and through music. If someone didn’t speak one of the standard versions, I considered the person to be a foreigner to the UK or the US like me — someone who learned English and tried their best to get as close as possible to the “correct” English that I learned in school.

Many things contributed to changing my perspective and adding to my knowledge when it comes to English varieties. For one, I grew up. I lived in Ireland for a year, where I encountered various dialects and accents. I started to watch movies in the original English, even if I sometimes had trouble understanding what was being said. Back in Germany, I enrolled in an English Studies program and fell in love with linguistics. We talked about the history of English, the role of colonialism, the development of different dialects and the role of white supremacy in language ideology.

Language fascinates me and with the poco.lit. podcast that a colleague and I started this year, I try to share this fascination. For one episode, I interviewed Olga Grjasnowa, author of Die Macht der Mehrsprachigkeit (the book has not been translated into English yet), about the power of multilingualism and the dialects we learn in school. Olga said: “Language is not just a question of social class, there are often racial components to it as well. Whose English or whose French is the right one? […] The standard languages we learn are always those of the [former] colonial powers, not necessarily the ones of the majority of speakers.”

A book I completely fell in love with recently is The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey. It tells the story of Aycayia, who is of Taíno descent and has been transformed into a mermaid by a curse. After swimming in the sea for centuries, she is lured by the guitar playing and singing of the fisherman David Baptiste. When US-American tourists catch her, David rescues her and takes her to his home. As she slowly loses her fishtail and transforms back into a woman, a tender bond develops between the two. Aycayia learns to walk again and meets Miss Rain, the only white woman on the island who, in the colonial tradition, owns most of the village of Black Conch, and her deaf son Reggie, who communicates in Sign Language. Miss Rain helps Aycayia to learn to speak again. In Roffey’s book, the colonial history of the Caribbean is central, encompassing occupations by Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands and Great Britain.

The representation of linguistic diversity is impressive, ranging from Standard English to Indigenous languages, Creole languages and Sign Language and with this, Roffey’s novel points to the colonial continuities in the languages of the Caribbean. The reader is introduced to an English Creole language within the first pages of The Mermaid of Black Conch. The island St. Constance and the place Black Conch, where the story is set, are fictional and represent the broader Caribbean region instead of a specific country. Throughout the book, Roffey refers to the language spoken as Black Conch English (BCE), which carries strong features of Caribbean English Creole (CEC). Even if these features of CEC vary depending on the speech situation and character, they form a consistent picture of the language spoken by the people of Black Conch. Readers get the impression of a speech community that distinguishes itself in its language use from the US-American tourists Thomas and Hank Clayton. BCE is part of an identity that encompasses not only personal and social aspects but also includes a spatial identity. However, Roffey goes even further by showing that linguistic identities are more complex: The three main characters question their own language use, which is closely connected to the colonial past of the Caribbean.

In one of David Baptiste's diary entries, in which he reflects on the events with Aycayia, he writes about his French surname, which can be traced back to the enslavement of his ancestors: “Though I always know who I was in Black Conch, family history don't go back far. That memory was rubbed out because of the badness of slavery. Baptiste is plantation owner name, French man name from way back.” (121) Due to the influence of colonialism, David does not know his real name: “I figure my real name would never be known to me, a mystery.” (121) With his last name, he is permanently linked to the oppressor of his ancestors and unable to answer questions about his identity: Where are his roots? Which part of Africa did his ancestors come from before enslavers brutally took them away to work on the plantations in the Americas?

The character Aycayia was cursed and turned into a mermaid, forcing her to live a lonely life in the sea. After hundreds of years, she transforms back into a human. She has unlearned how to speak and can barely remember her indigenous language but is also confronted with a completely new language, BCE. Roffey’s novel thus draws attention to the fate of the indigenous Taíno people, who either died due to diseases brought to the Caribbean by the Portuguese Inquisition or were murdered by the European colonizers. This shows that the linguistic diversity of the region has been reduced due to the language death of indigenous languages as a result of colonialism. On her own, Aycayia cannot revitalise the forgotten language — she cannot interact with any of its speakers. This leads to loneliness and a feeling of not belonging. With her speechlessness, Aycayia symbolises the irrevocable loss of indigenous languages, which have been displaced by European languages or Creole languages, like BCE, and are associated with identity loss.

Miss Rain speaks BCE, just like the other inhabitants of Black Conch. However, her appearance (as the only white woman on the island) and her wealth distinguish her from the others. The US-American tourist Hank Clayton sees her whiteness as a sign of Europeanness and is shocked that she does not speak standard English: “... she spoke just like the local fishermen, in the same slow, rhythmic, broken-down, backward English.” (46) Initially, he denies her a shared social identity with the inhabitants of Black Conch based on her appearance and categorises her in the tradition of white superiority as European. This presupposes a use of Standard English, which he associates with a specific education, which he immediately denies her based on her language. At the same time, this means that he does not recognise her as his equal. This results from a long tradition of linguistic ideologies that judge Creole languages as inferior languages and consequently regard the speakers as uneducated.

Reading the Mermaid of Black Conch was as revelatory for me as translating song lyrics in the past. Both opened worlds for me and broadened my perspective. Thanks to Roffey’s novel, I came to realize that postcolonial literature can help us to understand the role of language, its importance in shaping an identity and its connection to social hierarchies.

Nationality: German

First Language(s): German

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by:

Comments on "The Role of Language and Postcolonial Literature in Shaping Identity — A Personal Essay"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login