Published December 22nd, 2025

Other

by Ebenezer Mowete

There’s a certain loneliness that comes with thinking in one language and writing in another. It feels like standing between two mirrors — your reflection never quite aligning, always split, always searching. For me, English was never the language of home. It was the language of textbooks, of exams, of trying to sound like I belonged in a world that didn’t always feel like mine.

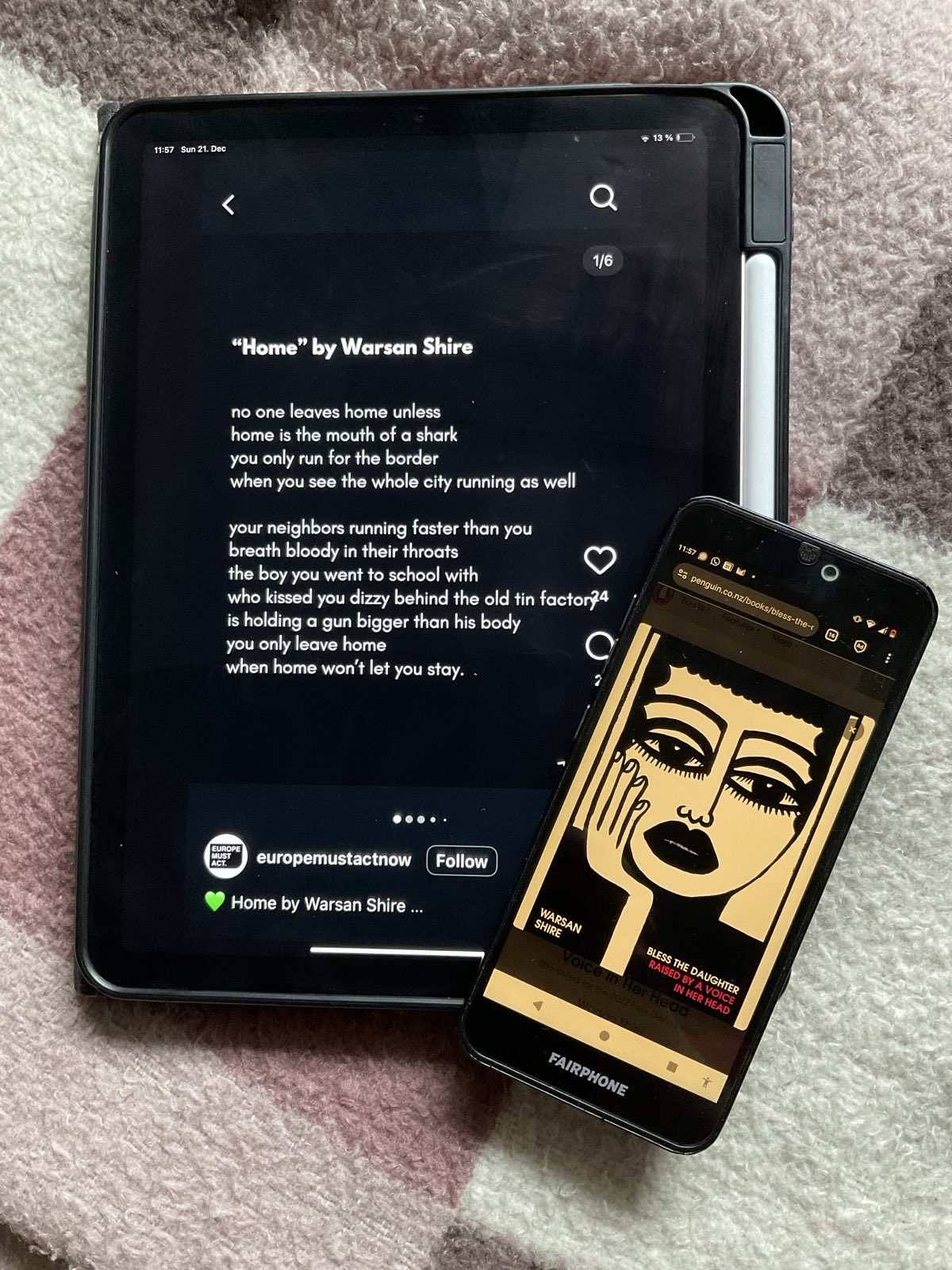

And yet, it was through English that I first found the voice of Somali-British poet Warsan Shire — a woman whose words seemed to burn through every border I had ever known.

I met her poetry the way many of us did: online. Fragments of her verses floated through timelines, shared by strangers who didn’t always know her name but felt the truth of her lines.

No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.

(from “Home”)

Those words stopped me cold. They carried the weight of exile, of silence, of survival. They carried something I didn’t yet have the language to name.

I didn’t know then that Shire had moved to London at the age of one — that English had likely grown alongside her, bilingual and breathing. But maybe that’s what drew me in: her ability to make English sound foreign again. Her poetry didn’t bow to grammar. It resisted neatness. It pulsed with the rhythm of something older, something ancestral.

In “Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth,” she writes:

I have my mother’s mouth and my father’s eyes;

on my face they are still together.

That line felt like a mirror. I, too, have tried to bring my parents’ world and my own into the same sentence. Writing in English sometimes feels like translating memory — like trying to preserve the scent of rain in a jar. There’s always something lost in the retelling.

Shire’s work taught me that what’s lost isn’t always failure — it can be transformation. Her English doesn’t imitate; it remakes. It carries echoes of Somali storytelling, of Quranic cadence, of oral traditions that refuse to disappear. Through her, I began to understand that the language of the colonizer could still be claimed, bent, and reborn.

When I write, I carry that lesson with me. I no longer chase the perfection of “Standard English.” I chase resonance. I chase truth. I chase the trembling between words — the accent, the hesitation, the places where my other tongue still peeks through.

As an ESL writer, I’ve learned that my voice lives in that in-between. It’s not polished; it’s lived-in. It bears the fingerprints of other histories, other music. Reading Shire gave me permission to stop apologizing for that. To see beauty in linguistic rebellion.

When Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” amplified Shire’s words to millions (read about it here), it wasn’t just a cultural moment — it was a reclamation. A Somali-born poet, writing from the fractures of identity, shaping the sound of global pop culture. It reminded me that language, like people, migrates. It learns to survive.

Writing in English will always feel, for me, like walking through borrowed rooms. But in Shire’s work, I’ve learned how to rearrange the furniture — how to make those rooms echo with my own stories.

Maybe that’s what literature does at its best: It turns language into a home, even for those of us who arrived through exile, translation, and longing.

Nationality: Nigerian

First Language(s): Igbo, Pidgin English

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by:

Comments on "Between Languages — How Warsan Shire Taught Me to Speak in Silence"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login