Published July 31st, 2023

Interview

by Tim Tim Cheng

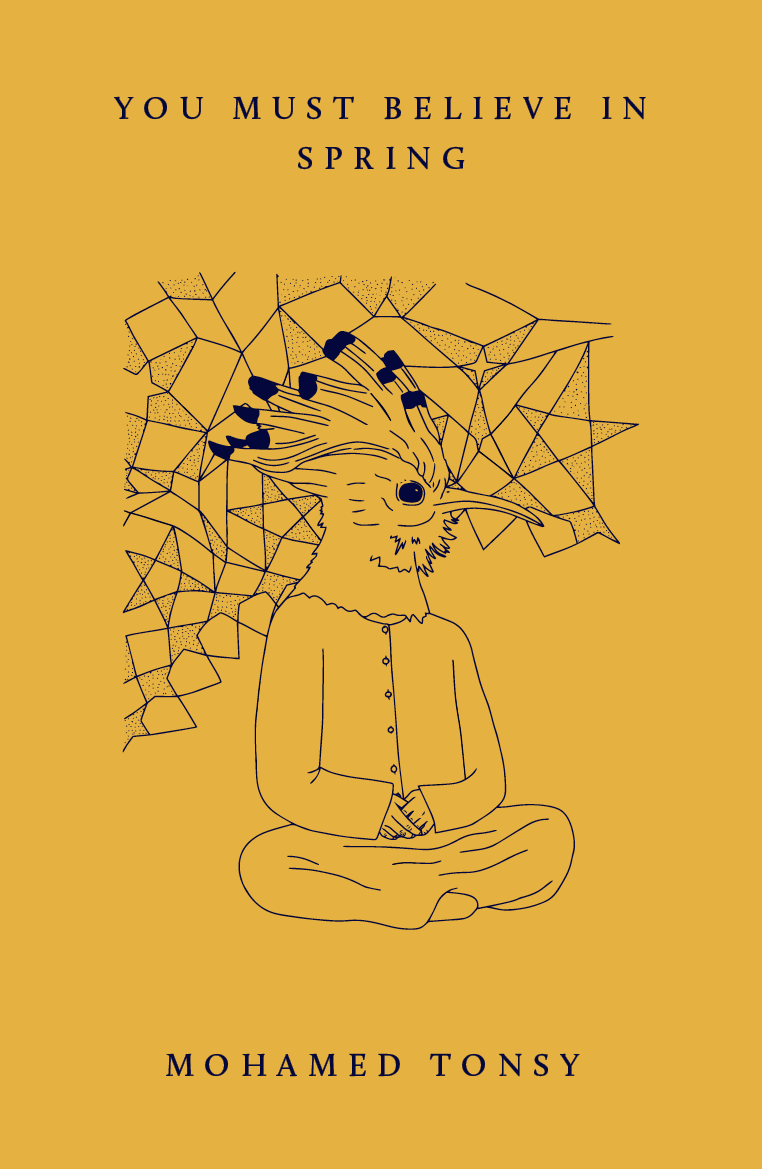

I knew Mohamed Tonsy's novel would be important to me the moment I read its title: You Must Believe in Spring. Spring, as in a transitional season, as in a water source, as in a sudden forward movement, as in the Arab Spring.

Having completed my creative writing masters in Edinburgh to write about and beyond my protest-stricken home city, Hong Kong, I am entrenched in the complex relationship between writing, healing, and power structures. The most important questions to me are: what drives us to do what we do, despite it all? Where does the imperative must come from?

Mohamed Tonsy's book does not give easy answers. It took me a long time to push through the echoes between the novel and my lived experiences among many politically oppressed people.

You Must Believe In Spring is set two decades after the Arab Spring of 2011. As the Nile is drying, Shahed, a national swimmer and a disciple of the Sufi institute, wades through suppressed inter-generational memories. As the son of intellectuals exiled in Europe, Shahed is raised in his estranged homeland by his grandmother, who stayed witnessing a different Egypt. Past curfew checkpoints, dream states, and a prison town in the Sinai desert, Shahed navigates ways of resistance, traumas, and the price of freedom.

I chatted to Mohamed Tonsy after his intimate and poignant book launch at Typewronger Books, a bookstore in Edinburgh, earlier last year.

Tim Tim: Thank you so much for the book. I enjoyed reading about how Shahed finds his personal space in swimming. There are such beautiful descriptions, such as how the bubbles he exhales as he swims are words he cannot say. It is also interesting how an activity that soothes and gratifies him is also a tool for the government to gain national prestige. How did you come up with this characterisation?

Mohamed: That was something that came directly from my own life experience. For athletes in niche sports (of which triathlon is one) the Egyptian Armed Forces is one of the few institutions that was ever willing to invest and pay for athletes’ training. It was quite an odd moment when I first started representing the national team since I had to sign a document stating that I choose to represent the Egyptian Armed Forces — not the country, but the Armed Forces. It was especially frustrating given that it was the only way to get a team going, hope to get funding, and find a way to race in internationally recognised races. The utility of that position for the armed forces became quickly apparent. I was asked to speak at conferences discussing the sport, did interviews where the president of the federation repeatedly hinted that I must feel superior to my university cohort given what I do. The final hint of the real value of what I was doing was how ecstatic my father was at hearing the news. He never supported my competing, but when he heard of a connection with the armed forces, his reaction was “That’s amazing! You might even get an honourary rank.”

-lee-lewis.jpg)

At the same time I met some of my closest friends through the sport. Mohamed el-Saied is one of those people, an incredibly talented athlete and hard worker, we trained together in Nady el Shams. He was my biggest support. We were both studying at that time, so we would occasionally show up late to training, which meant we had the track to ourselves. During the warm-up we would vent about our days, but once we started the main training set we would just focus on the workout. There were times our bodies would find some magic sort of synchronicity, and we would only hear one set of footfalls, with both of us moving as one. Experiences like that definitely made me think of the possibility of expressing the inexpressible through movement, completely apart from languages that might seem oppressive, or restricting to our personal experiences. The challenge was to get that across to readers in a way that they might share that moment too. So, yeah. Sports was definitely a refuge, a time when I could let myself move and have that echo what I was feeling, or not feeling.

Tim Tim: Why is it important that the book is set in the near future of the 2030s?

Mohamed: It was something that came out of sheer necessity. The revolution’s history was being rewritten by el-Sisi’s authoritarian regime when I started writing it in 2016, making it seem like the military was the natural and only successor possible in the aftermath of 2011. Amazing works have been written that have recorded the revolution’s history — including Omar Robert Hamilton’s The City Always Wins, Yasmine el-Rifae’s Radius, Sherine Hafez’s Women of the Midan, Sarah Tonsy’s The Egyptian Army and the Muslim Brotherhood, Sara Salem’s Anticolonial Afterlives of Egypt, Radwa Ashour’s Athqal mn Radwa, Alaa Abd el-Fattah’s You Have not Yet Been Defeated — but I found myself drawn to that terrifying feeling of loss I was experiencing, and trying to imagine what would be left for Egyptians living in Egypt who only have the resources that the state allows? Hence the reason for setting it in the future, I wanted to imagine what would be lost, how the histories we’ve lived through will be used: will they be seen as inevitable, or as one of many outcomes that we happened to live through? Will martyrs be remembered and honoured, and if so, which martyrs? What will the stories that filter through say of our identity as Egyptians, and can we imagine that identity as separate from our suffering, or is that its own form of violence?

Also — and this was something I realised much later on — part of it was therapeutic in that it was a way to process my own trauma. Complex trauma means certain episodes can keep repeating themselves and exist somewhat out of context, in a way that’s impossible to integrate into the narrative, episodes of violence, for example. Setting it in the future allowed me the space to incorporate that return to those episodes within the revolution, and have it work as part of the narrative.

Tim Tim: What does code-switching between Arabic and English mean to you?

Mohamed: For the novel, I felt like I had to come up with an in-narrative reason for the narrative existing in English rather than the Arabic that the events are lived in. I wanted the Arabic breaking through the English in the text to work on several levels. I wanted it as a way to impart onto the reader the sense of alienation that the protagonist experiences, the language the reader interacts with doesn’t reflect the experiences Shahed is living. The Arabic disrupting the flow of English on the page is a manifestation of what the compulsive sense of narration — Shahed’s wordiness and awkward turns of phrases — tries to hide, that his manipulation of language doesn’t mean he’s in control. He’s desperately trying to weave the English language in a way so he can regain control of his narrative. The Arabic reveals the cracks.

To borrow Alaa Abd el-Fattah’s phrase, it’s the “ghost of spring past” showing through the coping mechanisms the narrator has built up around him. Also, I think it’s important to point out that the Arabic used in the text is a very local dialect of Arabic. This was done so it can remain faithful to the language that would be used on the streets in Egypt; if the novel were written in Modern Standard Arabic, the Arabic written in this text would still stand out as being colloquial. To use an analogy from my pottery practice, the Arabic is the shadow cast beneath the shape inviting the viewer to pick it up.

What this linguistic choice means for me personally, I honestly can’t tell you for certain. It’s easier to answer its function within the novel than it is to answer what it means for me. I tried to write about this exact topic in an essay that was published on the John Byrne Award website called “Where do we go when language fails?” In the essay I discussed how English terminology allowed for easy shelter when it came to reflecting on my identity, but that something still kept getting lost in translation. I talked about how the English word ‘bisexual’ seemed to fit well when I was first exploring my sexuality, but that it started falling short as time went on. I can’t really think of this question without reflecting on the colonisation of language that marginalised communities go through. This question only exists because I went to an international school, before studying in the American University in Cairo for my undergraduate studies in architecture. And those structures that emphasise teaching and learning in proper English only exist because academia in the colonies was only created to study the colonies themselves.

In that sense, Arabic is a refuge where I don’t have to fit within neat categories, where I don’t have to tick “Other” when choosing my ethnicity on diversity and inclusion forms, but — and here, more contradictions — the beauty of any language is that it is mutable. So, there is a way to find more room to breathe in what can sometimes feel like a constricting language. There’s quite a bit of overlap in my life as it is lived in both languages now, but that wasn’t always the case. I’ve given up trying to assign where each part of my identity and life is meant to exist, and that’s my own small act of resistance to power structures that tells me that I must be easily legible, and identifiable when it comes to my place in the world.

Tim Tim:There are some parallels between the characters' lives and your own (as stated in your foreword and acknowledgements). How do you tell writing and healing apart, if that is a needed distinction?

Mohamed: There’s definitely an important distinction to be noted between both. For me, writing can be therapeutic, and has felt therapeutic, but it is not therapy. I realised that given a few similarities, readers were bound to read me into the narrative. Since the book’s publication, I’ve gotten numerous questions from readers asking me about my experience doing something that Shahed had done, and I found myself needing to apologise and say, that was purely fiction. I think that’s something that a lot of writers of colour go through, the need to contend with how their fiction aligns with their own lives, so rather than dismissing it, I decided to blend both, to play with the readers’ expectations.

And, I guess that’s the bit that’s felt most therapeutic to me, the ability to create myth and fiction out of reality, and realising that a narrative doesn’t have to exist as a sole monolithic entity that’s unchanging. It feels like quite a vulnerable thing, to write in a therapeutic form, for an audience. I didn’t think I could do it, but still I realised that I needed to write this story, so I created this elaborate device to make it possible. Maybe, to try and return to your question, the writing process and creation of the narrative just creates more space around the events that need that therapeutic process, but still, having gone through therapy — and having had my therapist highlight interesting points within the narrative connecting my therapy to my writing — I would say that therapy can start at the page, but it shouldn’t stop there. Once you create the thing, what do you do with it? I think that’s the question that my experience with therapy tried to answer.

Nationality: Chinese (Hongkong)

First Language(s): Cantonese

Second Language(s):

English,

Mandarin

Supported by:

Comments on "The Inevitability of Spring — An Interview with Mohamed Tonsy"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login