Published November 24th, 2025

Interview

by Srijani Mitra

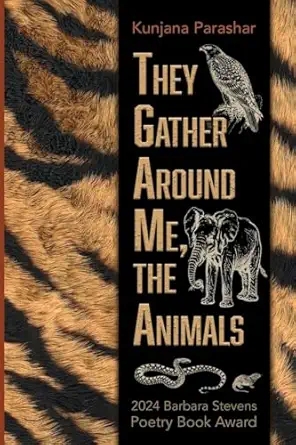

Kunjana Parashar is a poet based in Mumbai, India. Her debut poetry book, They Gather Around Me, the Animals, selected by Diane Seuss, won the 2024 Barbara Stevens Poetry Book Award. She is also a recipient of the Toto Funds the Arts award and received the Deepankar Khiwani Memorial Prize. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Northwest, Sixth Finch, The Adroit Journal, Eunoia Review and The Rumpus. She is the Managing Editor (Poetry) at The Bombay Literary Magazine.

Srijani Mitra: Could you share the story behind They Gather Around Me, the Animals being selected by Diane Seuss for the 2024 Barbara Stevens Poetry Book Award?

Kunjana Parashar: There is no grand story as such. I was bored and sort of done with my manuscript and had this itch to send it out somewhere just to test the waters. I decided to send the manuscript to a few competitions. I think I applied only to four or five places because the submission fee was steep and I didn’t want to waste too much money. And I applied to this competition in particular because Diane Seuss was the judge so I thought this must be a legitimate prize. Two months later or so, I got an email from Eleanor Berry, Chair of the Stevens Manuscript Competition, informing me that my manuscript had been selected. I remember my first reaction was frowning at the email in confusion. And my second reaction was to be scared because I didn’t know or fully understand what had happened or what this meant.

Srijani: What was your inspiration to write this book?

Kunjana: To be honest, it just felt like it was time to perhaps start gathering some of my poems into a book of sorts. And when I saw that a common theme holding them together was the presence of animals, I decided to go ahead with it.

Srijani: Your collection explores both the presence and absence of animals, intertwining celebration with elegy. How did you combine those tones?

Kunjana: I wasn’t conscious of what I was doing while I was doing it. But I remember that when I had first put together the manuscript, there were a couple of poems whose energy was not one of celebration. These were “Poem with No Dogs in It” and “The Creature.” And on further thinking, I realized that I would like to lean into more of that kind of energy. This led to me writing a series of poems where a species had gone missing or was absent. While I was okay with poems of celebration, these poems of absence seemed real too, and plausible, even though their worlds were speculative. It felt urgent to write these poems and to further write into and from that space of urgency.

Srijani: Your poems beautifully portray scientific sensibility along with a certain divinity. How do you feel that the natural world and environmental consciousness inform your work?

Kunjana: I don’t think I fully understand or grasp that there is a difference between the two. Everything seems to be somewhat on the same spectrum. I guess if you like the natural world, an environmental consciousness will follow. How does it inform my work? I’m not sure. All I know is that animals occupy a prominent space in my mind.

Srijani: Your book has a diverse range of poetic forms: There are odes, pantoums, as well as erasures. Could you walk us through your creative process in choosing such forms?

Kunjana: The pantoum was my editor’s idea, Sohini Basak. So was the burning haibun. I’m super grateful to her for gently nudging me to employ these forms. Sometimes you don’t know what’s best for your poems and you’re too shut off to new possibilities. This is why it helps to have another pair of eyes read your work and provide feedback. Odes, on the other hand, come more naturally to me so there wasn’t too much creative jostling entailed therein. There was no elaborate creative process or ritual involved in the entire process. It was just like playing and experimenting.

Srijani: What role does language, especially the ecological lexicon, play in shaping the emotional impact of your poems?

Kunjana: I am not sure I can answer this without some degree of uncertainty. How does one employ language to shape the emotional impact of their poems? I think you can’t. I mean you cannot be totally conscious of what you are doing and exactly at what point you might successfully devastate your reader. I have trouble sometimes gauging the emotional quotient and potency of something. I am not aware of how I come across to others. Similarly, I am not aware of how my poems come across to others whether I use ecological lexicon or not. I am of the opinion that as long as you’re balancing ecological words or more scientific-sounding words like zoanthids and corvids with something regular such as car, pain, chalk, or spider, you will be fine.

Srijani: Lines such as “whales slap on the coast like fingers on guitars,” and “rain falls like a bag of teeth on tin roofs” are vividly sensory. Could you talk about your approach to creating these striking images?

Kunjana: There is no fixed approach. Sometimes your brain is active and open and receives the right beeps and signals and all the words in your head jangle to make a certain kind of song. It could be sonorous or dissonant. Same with images. Sometimes something opens up in the spheres above your head and you’re not entirely aware of what you’re doing but you end up finding a resonance across dissimilar things.

Srijani: The emotional weight of your poems, in their absence of bird songs or howls of dogs, suggests deep loss. How does absence function as a poetic and ecological device in your work?

Kunjana: I wasn’t aware of what I was doing. All I knew was that I had to write about this void in my gut when I imagined a world without the presence of dogs or birds. My job was to materialize this absence, give it a shape, mass, texture, and actualize it in verse. Language is an attempt to make the state of absence literal, to reach for it, to help it be imagined.

Srijani: What does “ecological imagination” mean to you? How do you envision its importance in contemporary poetry?

Kunjana: To me, it means that you’re thinking on a level that is beyond your own, that goes beyond personal gain. You’re thinking macro, big-picture. You’re aware of small things like how a dead tree is a microhabitat and how it is not “useless” or “unnecessary.” I read in a magazine once how when an elephant walks, she leaves a small puddle-sized imprint in the earth and that this puddled pool then becomes a breeding place for tadpoles. How life propagates life. How decay is a part of the cycle of proliferation and vice-versa. It means you are careful about what belongs and what doesn’t, what is invasive and what is endemic, what you can take & what you must replenish.

About how I envision its importance in contemporary poetry as a whole, I don’t know, but I try to remember what Jorie Graham said. What she said is essentially this: People tend to ignore you and think you’ve gone cuckoo and are being didactic and preachy if you yell “Wake up, climate change is real!” in their ears. They don’t want to listen to that, they think they already “know” this information. So what can we do as poets, how do we break through? We can use language in a way where facts such as species extinction and global warming don’t just remain facts or reportage, but turn into something that can be “felt” and can be “imagined” by anyone reading your poems.

Srijani: What role do animals play in your life beyond poetry? Are there personal experiences or relationships with animals that informed specific poems?

Kunjana: I dig animals in real life too and if you flash me the inner pocket of your coat and I see a hornbill peeking its giant helmeted head from out there, I just might sign up to your cult and change my religion. But most of the poems in my first book have stemmed from imaginary interactions with animals.

Srijani: Looking ahead, do you foresee continuing this path of ecological and poetic exploration? Are there new forms or themes you are eager to experiment with next?

Kunjana: I guess animals will keep turning up in my poems inadvertently. For now, I have sent my second manuscript out into the wild land of submissions. This second one is definitely a lot more about my relationships with other humans. But these days, I’m getting more interested in the poems of Russell Edson. So I am trying to imitate his style of writing. I’m thinking about surreal and absurd poems.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bengali

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by:

Comments on "Ecological Consciousness Imbibed in Poetic Sensibilities — In Conversation with Kunjana Parashar"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login