Published February 5th, 2024

Interview

by Ines Rodrigues

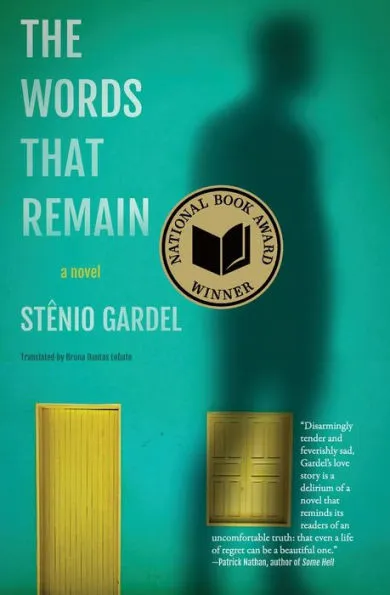

When we did this interview, Bruna Dantas Lobato was in a celebratory mood. Our conversation happened a few days after she got the National Book Prize for best-translated literature in the US for the book The Words That Remain by Brazilian writer Stênio Gardel. This is the first time a translation from Brazilian Portuguese has received such an award. A prize like this doesn’t come easily. Over the years, Bruna’s own fiction writing has appeared in US publications such as The New Yorker, Guernica, A Public Space, and The Common. Her first novel, Blue Light Hours, is forthcoming in October 2024 from Grove Atlantic in the US and Companhia das Letras/PRH in Brazil (in her own translation into Portuguese).

Months earlier, I had met Bruna for the first time, in a panel about Brazilian translation in New York, where she fiercely defended her ideas. Right there I could recognize what a great fighter she is. She takes her writing very seriously and proves that becoming successful — especially in her second language — is the result of a lot of dedication, besides a great talent for words. She left her hometown of Natal, in the tip of Northeastern Brazil, when she was only eighteen, to take advantage of an opportunity to study abroad. Later, she not only graduated from Bennington College, but also got her MFA in Fiction from New York University and an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Iowa.

“Now it’s hard for me to imagine writing outside of English, or even being a writer without my relationship to this language.” (Bruna Dantas Lobato)

Bruna is Brazilian, like me. I feel the same way she does about the experience of writing in English. Although we come from very distinct regions in Brazil, our common language and our initial struggles to write in English are the same. She’s from Natal, in the Northeast of Brazil, and I’m from São Paulo, in the South. Our conversation in Portuguese flows easily, and I love the Northeastern accent she has preserved, reminding me of my own mother who’s also from that region. Bruna says that her accent in Portuguese becomes a barrier in our own country because it’s not the standard accent of our Southern big cities and, therefore, not perceived as particularly sophisticated. She adds a very interesting fact to that: She navigates different cultures more easily with her acquired global English.

While I talk to her, I recognize the talented person who had to climb every little step up in her career with a lot of hard work. While she was learning to be a writer in her second language, she also had to deal with loneliness, homesickness, prejudice — the usual problems immigrants must face in a foreign land. Nothing came easily, but she’s not afraid of a good fight. Learning how to write in English also gave her something fundamental to be successful: confidence. Now, preparing for another big task of launching and promoting her first novel, she proves again that she doesn’t get intimidated by a big challenge.

Ines Rodrigues: In your story “Snowstorm”, published in The New Yorker in 2022, there’s a paragraph where your character is looking for something to read to her mother: “I looked around my room for a book in Portuguese, something we could both understand and then I realized there was nothing. All the books around me were in English, and every flier, magazine, brochure. Even my own diaries.”

When did this turning point happen in your own life? Did you have a moment of realization, as your character in the story, that even your diaries are written in your second language?

Bruna Dantas Lobato: Pretty early on, unfortunately. I was the only student from Brazil at my college and an English major to boot. I’d been told that if I wanted to do well in school I had to be fully immersed in English, call home less and less, sever ties with my language. Everything Brazilian about me got eliminated or neglected and I started to resent the expectation that I couldn’t do both, that I couldn’t be a Brazilian person at home who also spoke and wrote in English elsewhere. There wasn’t one moment of clarity — it was more of a slow burn: I’d changed before I even knew to try to stop it. I had to undo a lot of those misconceptions once I was out of college, and to find my way to Portuguese again, and my work with translation has been a huge part of that.

Ines: Do you still write stories in Portuguese? If so, how do you feel your voice differs as a writer in Portuguese and in English?

Bruna: I’ve never written much in Portuguese, except for the diary entries I wrote growing up, but I’ve always wanted to. When I started to write fiction in college, I was newish to English and set out to play with the limits and strangeness of my new language. Now it’s hard for me to imagine writing outside of English, or even being a writer without my relationship to this language, though I would still like to try. I’m now in the process of translating my novel into Portuguese and it’s my first time writing and translating literature into my mother tongue. My Portuguese is rusty, foreign in my mouth, but now I know enough to know it’ll get better with practice, the same way my English did, and that I can use this feeling of estrangement on the page. I’m curious to see what will come of this experiment, and I’m so grateful this book has finally given me the chance to go back to the first language that shaped me.

Ines: Has your relation to Portuguese, your native language, changed after so many years abroad?

Bruna: It definitely has. Now I see it as a familial language while English is my work language. My Portuguese is spoken and informal, more regional and specific to the place where I was born in the Northeast of Brazil, while my English is expansive and can easily move across countries and centuries and dialects. I’ve since learned to reclaim my hyper-specific Portuguese and to be proud of it, but I’m still aware of the fact that it steers away from the dominant Portuguese of the big metropoles, that I don’t naturally belong to all of Brazil in Portuguese the way I’m able to find ways to belong in more and more places with my global English.

Ines: Why did you decide to leave Brazil and come to study in the US?

Bruna: It wasn’t exactly a conscious choice. I was eighteen and poor, a smart and ambitious public-school student, and there was an opportunity for me to travel abroad for the first time to study in the US. I couldn’t say no to a possibility like that. At the time, I didn’t know how permanent and serious of a decision I was making, of course. I didn’t know four years in college would lead to five, then a decade. Life happens and takes you to unexpected places sometimes, and I’m glad that while all of this was happening, it was taking me to a life in books.

Ines: Do you remember any curious or funny story related to language gaffes or misunderstandings between English and Portuguese?

Bruna: This is a tough question for me. I’ve misunderstood and misspoken many things in my first few years, but I never found it funny per se. When I was younger, I remember feeling vulnerable and silly, and utterly ashamed, every time I mispronounced something, maybe because I took myself too seriously. Now that I’m older, I’m more relaxed and can easily laugh at myself, but I don’t make those kinds of mistakes anymore. I’ve kind of missed my chance to enjoy that part of the process.

Ines: You do significant work as a literary translator. How do you choose authors to translate? Also, tell us a little bit about how you “sell” a specific translated author to the US literary market.

Bruna: I only translate writers whose style I feel like I can emulate in English, or who I can somehow embody on the page and mimic. Sometimes, they land on my desk through an agent’s or an editor’s recommendation, and other times I seek them out myself. If I really believe in a book and author, I’ll advocate for it and send pitch letters to editors who might be able to see my vision. It’s a labor of love and a lot of matchmaking goes into it — I’ve got to find an editor to fall in love with it the same way I have, and that takes a lot of effort and time.

Ines: How does your work as a translator feed the fiction writer, or vice-versa?

Bruna: I don’t think I’d be able to do one without the other. I have to be a good writer in order to translate, to have a solid understanding of voice, pace, dramatic tension, structure, character development, and style. If the wrong line falls flat, the whole book can fall apart. I’ve learned a lot from translating all these great books and have only become a stronger writer with time. Caio Fernando Abreu, especially, taught me a lot about how to sustain tension and dramatic effect, and I’ve used a lot of those skills in my novel.

Ines: Tell us about your first novel, Blue Light Hours, which will be published next year simultaneously in Brazil and in the US.

Bruna: It’s a portrait of a mother and a daughter coming of age together and apart, across borders, and the relationship they develop over video calls. The blue light from the title comes from their phone and computer screens, always shining on their faces, a cold surface bringing them together and keeping them apart. I hadn’t been able to find a novel that fully captured my experiences as an immigrant in the 21st century or novels that fully conveyed the fragility and tenderness of the mother-daughter bond. So, I felt like I had to write it, to present the world as I saw it. My hope is that this book can show life in-between countries in a new light.

Ines: What are your favorite authors in Portuguese and English? Who truly inspires your writing?

Bruna: All the Brazilian authors I’ve translated have had a huge influence on me, especially Caio Fernando Abreu and Stênio Gardel. In English, Jamaica Kincaid, Sigrid Nuñez, and Jean Rhys have taught me a lot about language and the immigrant condition. My novel wouldn’t exist without their work.

Ines: What’s your best advice to other ESL writers who are starting a career writing in English?

Bruna: Remember that everyone’s relationship to language is valid, including yours. Your English and your stories deserve as much space as anyone else’s. Once you start to believe that, the rest will come.

Nationality: Brazilian

First Language(s): Portuguese

Second Language(s):

English,

Italian

Supported by:

Comments on "Becoming Global in English: An Interview with Bruna Dantas Lobato"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login