Essay

by Kaori Fujimoto

If I were to list and explain Japanese words with no English equivalents, I would first give koi, which loosely translates as “love.” Japanese has multiple words that mean “love,” and ai (pronounced like “I” in English) and koi are the primary equivalents. Ai covers all major types of love: love for your family, partner, friends, and pets, or God’s love for all living things. Koi, on the other hand, refers exclusively to romantic and innocent love.

When I think of koi, I think of — along with some boys and men I once liked — the French language. This must sound odd, but the language had my heart when I was a little girl, and it still enchants me, in my middle years, though I don’t speak it fluently and probably never will.

Let me explain.

When I was a 9-year-old growing up in the Tokyo area, I fell in love with the images of France I created in my mind from reading the Arsène Lupin novels in Japanese translation. A gentleman thief, Lupin travels around France and beyond to steal and help the helpless, demonstrating his formidable intellect coupled with his foreign language skills. These novels vividly portray French landscapes and cityscapes, and the dialogues are peppered with simple French words (Oui; Non; Qui est la?) shown in Japanese characters (ウイ;ノン;キ・エ・ラ?), adding an exotic feel to the texts. I wrote down these foreign words in a notebook like collecting lustrous seashells on the beach. At age 10, I decided to become a French-to-Japanese translator, dreaming of frequenting the European country as an adult.

This was the first love I felt for a language that was not my own. And the word koi accurately conveys this feeling.

Japanese speakers would say you are in koi, instead of ai, if your heart beats faster as a certain coworker comes near and the longing to become closer to him might keep you awake at night. Or you frequent a bookstore, and maybe buy a book or two on each visit, only to have a glimpse of or exchange some words with the lovely woman at the cash register.

“Crush” or “infatuation” might be a close equivalent to koi in these contexts. However, native English speakers seem to use these words to imply that the ardor deserves mockery or dismissal for being absurd and short-lived. Koi can be dismissed as being silly, but it is also valued as a pure state of mind. Koi may last only briefly, or for decades, unrequited. Koi also constitutes an early stage of a relationship in which real-world problems have not yet challenged the couple’s love.

All this applies to my fervor for the French language. The novels and TV travel programs about France transported me into a reverie, making me yearn to speak it. But I didn’t take action to advance beyond this stage before the beginning of the end unfolded.

In ninth grade, I studied hard to get the grades needed for admission to a private senior high, and I turned out to do particularly well in English, a compulsory subject. Once I entered the private senior high, my mother sent me to a tiny English language school run by our relative, where I received lessons from my first American teacher. I spent a summer in the United States as an exchange student in a program my high school offered. While English increasingly occupied my time, mind, and heart, I hadn’t discarded my dream to become a French speaker. I tried to teach myself the language using self-study materials, an attempt to finally become intimate with my koi. Yet, somehow, French words and grammar refused to seep through my brain like English did, making me feel as if I were trying to bond with someone I was not supposed to. The decisive end came during my university years when I fell in love with literary works by British and American authors and started writing in English.

This second language continued to stay with me, serving as a source of joy and distress at the same time as I studied it and used it at work. In my twenties, I drifted away from it every now and then to learn Spanish or German, or do anything else that seemed to open an exciting new path for me like English had. But no matter what I did to wriggle out of the hold English had on me, I eventually found myself back with the language.

As you see, my first koi for a foreign language followed a typical course of first love: I never became close to the object of my desire before things changed. Once I knew in my bones I would become a writer in English, I was completely done with the koi.

Or so I believed.

I finally visited France in my early thirties, the age when I thought I would be working as a French-to-Japanese translator. Instead, I was a Japanese-to-English translator and had just left a chaotic job. For a vacation during unemployment, I picked France as a destination simply because it is a non-English-speaking country where a long-time friend happened to live. From my first day in Paris, I randomly walked through the city, unable to reach the end of one street because spectacular monuments, alluring water fountains, and lovely alleys beckoned me from every side. The street design that placed these distractions in just the right spots mesmerized me, and the historic constructions that filled the French capital had me in awe, while strewn trash on some of the streets made me recoil, and the aristocratic vanity that oozed from gorgeous structures made me grimace.

Yes, I can be ugly and I have an ugly past, the city seemed to whisper. Ugliness is part of my beauty.

At the time, I almost hated myself for all the ugliness I’d recognized in me, at work and in relationships, for being the person I was.

Be proud of where you come from, of being the person you have become.

This came as a punch — or a gift.

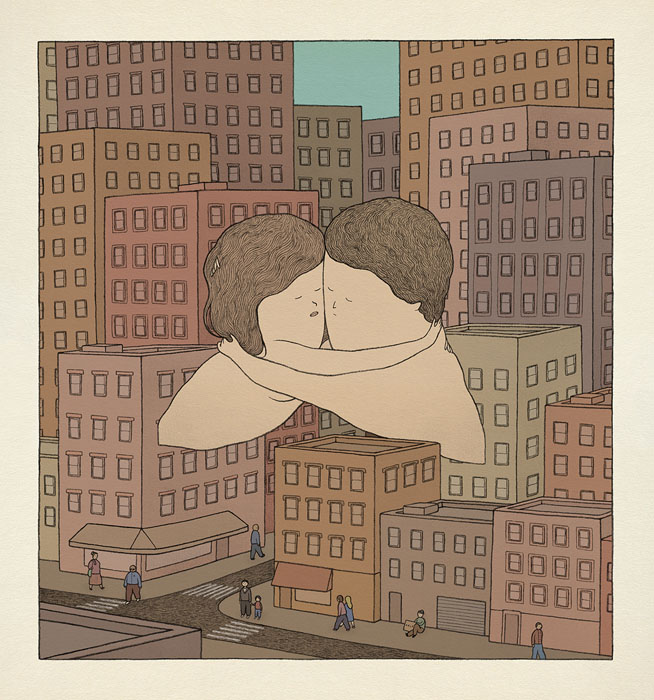

After this first visit, I kept returning to my childhood dreamland whenever I reached a crossroads. At those points in time, France was invariably out of my mind, but it unexpectedly showed up to beckon me back. The summons would come in the form of an invitation from a friend or writing workshops. Throughout these sojourns, France warmly embraced me in the cityscapes and landscapes I fantasized about as a little girl, and in interactions with kind locals. The country never demanded I learn its language, but instead nudged me to continue on my path with English, pursuing my career as a translator while writing in the second language. In the end, France gently let me go, filling me with the vitality I needed to live on away from my koi.

During those years, I slowly studied French in Tokyo. This time, the language did not resist entering my brain. I managed to reach the intermediate level, but I stopped going to the lessons partly because of my work situation, and mostly because I began to be afraid. I often found myself spending far more time than I should have on learning new words and expressions, my energy diverted from reading and writing in English, my life’s priority. Studying French was becoming not just a fun distraction, but a threat to the priority — a threat that could push English aside, like English propelled French away from my life.

Once more, the French-speaking world slipped from my grasp. Instead, my koi for the language remained romantic and innocent, with no history of heartbreak.

*

Fifteen years later, after working as a full-time freelance translator for a decade, after writing pieces that were published in American literary journals, I have resumed my French lessons. Now, despite my middle-aged brain’s limited capacity for absorbing a new language, I enjoy the learning process far more than I did fifteen years ago, knowing full well that France and French will never take center stage in my life. Opening the textbook to do homework, or hearing my teacher greet me at each lesson, really feels like seeing my first koi — a childhood dream — come true. French finally has a steady presence in my life, uplifting me whenever I feel unhappy in the world of the English language which, given its inseparability from my life despite all the hard times it has given me, must be my ai with no equivalent.

Appeared in Issue Fall '22

Nationality: Japanese

First Language(s): Japanese

Second Language(s):

English

Das Land Steiermark

Listen to Kaori Fujimoto reading "Koi and Love":

Supported by:

Comments on "Koi and Love"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login