Essay

by Galina Chernaya

Why do people always say you forget the pain of labor? I haven’t forgotten the pain of labor. Labor hurt. It hurt a lot.

The fact that I am not currently in pain and cannot simulate the pain of labor doesn’t mean I don’t remember it.— Nora Ephron, O, The Oprah Magazine, October 2005

As it is for most mothers, I remember the day I gave birth to each of my children as one of the most memorable days of my life, but even now, forty years later, the trauma of birth of my first child still stands out as an extremely vivid, hyper-realistic experience. Like most pregnancies in the Soviet Union, this one was unplanned. When I learned I was pregnant in May 1981, I was a 21-year old student in a Master’s degree program at Moscow University, from which I was due to graduate the following year in June. Abortions were legal and very common, but I did not consider this option. To avoid rumors of infertility, a married woman was expected to have a baby within the first three years of marriage, and my three years were already up.

I kept my pregnancy private, as was customary, and managed to go unnoticed until I was seven months along. It was already winter and finals were scheduled through the entire month of January, the last one being just a week before my February 6 due date. Like others in my situation, I was allowed to take the exams ahead of schedule. I passed my last one on January 13.

As if my baby knew exams were over, she woke up kicking on January 14. My first symptom of what was to come was severe back pain. There was no What to Expect When You’re Expecting or any other books about pregnancy in the Soviet Union and childbirth classes were unheard of. This meant that first-time mothers could only learn about pregnancy and labor from older women willing to share their experiences. My mother didn’t tell me much, except that giving birth to me, the youngest of her three children, was the hardest. “When your water breaks, you call emergency services,” was her only advice.

This is what I absolutely did not want to do. I knew that if I called 03 (the Soviet 911), I would be taken to any delivery hospital with an available bed. Delivery hospitals were separate entities from regular hospitals, and I could end up anywhere in Moscow. Even more importantly, the vast majority of Moscow delivery hospitals were hotbeds of staph infection, and there was no guarantee that the hospital I landed up in would be safe.

Luckily for me, my mother-in-law was a leading obstetrician-gynecologist at the USSR Ministry of Health. She had arranged for me to give birth at the Ministry’s Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, which had the best obstetricians in the country and was known to be staph-free. “It’s considered a bad sign if a doctor delivers a relative’s baby, so I will not be with you in the delivery room,” she advised. However, as a Department Chair at the Institute, she had full trust in her colleagues. “Don’t worry,” she assured me. “You’ll be in good hands.”

My contractions started in the early afternoon. At first, they were just uncomfortable, not painful. I was home by myself, but I didn’t call anyone because my water didn’t break. By the time my husband Kostya got home from work around 5:00 p.m., I was in real pain. Fortunately, the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology was only a ten-minute walk from the apartment. We left right away, taking nothing for me or the baby — due to fear of infection, no personal items or anything else from the outside was permitted in Soviet maternity wards.

The weather was brutally cold. I walked very slowly, hobbling with Kostya’s help from one street light to the next, stopping under each to take a deep gulp of air. The contractions were still slow, but more insistent now. I remember grabbing a lamppost, hard, and drawing in a sharp breath. The air was muffled and warm, and smelled of damp wool through the scarf wound protectively over my lower face.

At the hospital, the clock in the waiting area showed 6:05 p.m. We were taken to an examination room where I was checked for dilation and admitted. From this point on, it was all uncharted territory: No family members were allowed during labor or delivery. I took off my wedding ring and handed it to Kostya — jewelry was not permitted — and kissed him goodbye.

As expected, I was told to change into a patient gown and a nurse accompanied me to a labor prep room. Not expected was the next step, when a different nurse shaved off all my pubic hair with a single-edged razor. She made no effort to hide her disgust, and even managed to make a few nicks, which immediately started itching. Then came the enema to clear my bowels, and I was ready for the labor room.

Walking in, I was hit by the blinding glare of fluorescent ceiling lamps bouncing off the white-tiled walls. Totally white and antiseptic, the room shone from floor to ceiling with brilliantly reflected light. Two female nurses in uniforms and scrub caps moved among a dozen or so hospital beds, filled with women in various stages of labor all lined up in neat rows. The windows along the outer wall were also painted white to prohibit any prying exterior gaze from penetrating the room.

I was pointed to one of the few free beds in a corner. It was metal, with a thin, pallet-like mattress sheathed in pale oilcloth. I lay down — no sitting or walking permitted — and looked around with a feeling of mounting panic. Most women were moaning. One or two were in advanced labor, letting out terrible screams with every contraction. My immediate neighbor was crying, constantly calling her husband’s name: “Vasya, Vasya, what did you do to me?” she kept groaning over and over.

Two midwives on their hourly rounds moved routinely among the rows, checking dilation to determine who was ready for delivery. “Keep it up, woman! Yell! Scream so hard your voice gives out!” was their only encouragement. Every birth was natural — there was no pain management in maternity wards, and epidurals were a thing unknown. Being only twenty-one, I was emotionally unprepared to witness, let alone experience, such suffering.

My labor progressed, the pain became more intense, and I entered the realm of the screamers. After a few hours, I could not remember where I was or why. I was one with the excruciating pain, and all I wanted was for that pain to end. As I learned later, not everything was going well. My baby was suffering from asynclitic presentation — her head was tilted to one side, and she was unable to move down the birth canal in spite of intense contractions. The next eight hours melded together in delirium — echoing shrieks, the clock stopped dead on the wall, sweat streaming down my forehead, my teeth chattering from cold.

By 6 a.m., my baby was in extreme distress and my contractions had slowed. Unable to think of a better option, the doctor decided to stimulate contraction, and administered an intravenous drug. The contractions intensified until the pain became so unbearable that I tried to yank the IV out of my arm. Nurses roughly grabbed my hands, and I managed to bite one on the forearm. They tied me down and shoved an oxygen mask over my nose and mouth.

Fighting to escape, I’d heard the doctor mention “C-section.” Very rare in the Soviet Union, the procedure was reserved as a last resort in complex, life-threatening cases. “Let’s try one last thing,” a nurse said. “Call Andrusha.”

A huge male nurse suddenly appeared. He knew exactly what he’d been called in to do, and exactly how to do it. And lucky for me and my baby that he did — for his job was to perform the Kristeller Maneuver, or “fundal push,” a harrowing, high-risk procedure that carries the threat of uterine rupture and infant brain damage.

Looming over me, he placed the flat of his big palms on my stomach, bent over, and with all his strength, pressed the entire weight of his upper body down against my belly. I screamed at the top of my lungs, feeling as if every vessel in my body had burst at once.

But it worked! Tearing everything on her way, my baby daughter finally ripped her way out at 8:20 a.m. A nurse lifted her in the air to show her to me. Poor baby! Her head was one big, purple bruise, with a groove on the left side from banging for hours against my pelvis. The nurse whisked her away without letting me hold her. This was protocol: babies were always separated from their mothers at birth. A few minutes later, the same nurse came back to give me the statistics: my baby girl weighed 6 pounds, 6 ounces, and was 19½ inches long (3 kg, 50 cm). Her oxygen level was a bit low, but otherwise she was healthy. I was flooded with relief.

But it was not over for me yet. I was badly torn and had to be sutured. Again, no anesthesia of any kind was used. Writhing in pain, I asked the midwife stitching me up how much longer it would take. “It’s over when I’m done,” she barked. When she finally tied the last knot, I was not wheeled into the recovery room, but was left uncovered on a gurney by a drafty window in the corridor and forbidden to sleep for two hours. A nurse came by every fifteen minutes to keep me awake and check I hadn’t died of internal bleeding or other complications. “Woman, no sleeping!” she growled, whenever I closed my eyes.

Around 9:00 a.m., it started to lighten up outside. The sky above the surrounding buildings was turning deep red, the color of the stains on my gown. It was mid-January, the coldest time of the year in Moscow, when daytime temperatures rarely rise above -20°C (-4°F). A red sunrise signaled an exceptionally cold day ahead. And indeed, January 15, 1982, the day my wonderful daughter came into this world, was bone-chilling cold.

After the obligatory two hours in the hallway, my arms and legs numb from cold, I was transferred to the maternity floor. I was the last new mother to be placed in the room. Most occupants were women I’d seen in the labor room. All ten of us had given birth the same night. At last, I could sleep.

When I woke up, I crawled out of bed and stumbled to the sink at the front of the room. One look in the mirror, and tears started coming down my cheeks. I didn’t recognize my own face — eyes red with burst capillaries, face bruised and heavily marked from the oxygen mask, tangled hair, oily from sweat, clotted with dried blood. The sutures made it so painful to walk, I barely made it back to bed.

There was no toilet in the room, and walking down the corridor to the bathroom, an endeavor in itself, was even more difficult because I had no underwear. In the firm belief that airing stitches promoted healing, no underwear was permitted in the hospital. Instead, women were given two pieces of cloth a day to absorb vaginal discharge. Walking required taking tiny steps while tightly squeezing the cloth between my legs. Like Japanese women walking in kimonos, I thought as I tottered down the hall, though our ugly, bleached hospital gowns were certainly no match for beautiful, Japanese silk robes.

In the movies where people have babies, they are sitting in a hospital bed with flowers everywhere, beautifully made-up, with a baby in their arms and it is all very lovely. Anyone who has been in that zone will know it’s total fiction. It’s a truly, truly murderous business. Giving birth is a violent thing to go through.

— Tilda Swinton, Marie Claire, May 2011

Since neither the mother nor the baby endured permanent damage, my delivery was considered perfectly normal. Even so, hospital rules required a minimum one-week stay in the maternity ward, during which no visitors were allowed. The only way fathers could “visit” their wives and newborns was to stand outside the tightly sealed, winterized windows, and hope to hear a few words through the glass. I asked Kostya not to come, but the woman in the next bed, who turned out to have been next to me during labor as well, wanted to see her husband daily.

Yana was eighteen and a newlywed. Her husband, Vasya, also eighteen, showed up by the window several times a day. Most of the time he was drunk — he’d been celebrating the arrival of his baby daughter since the day Yana gave birth. “These stitches really hurt!” Yana complained, shouting through the window. “They didn’t sew up your hole, did they?” Vasya yelled back through the glass. Everyone in the room giggled.

All newborns were swaddled and kept together in a single room away from their mothers — again, from fear of infection. A two-factor identification system was used to avoid confusion: Immediately after birth, the mother’s name, baby’s gender, and delivery date were hand-written on two small squares of oilcloth. One tag was tied around the newborn’s wrist, and the other was attached to the baby’s swaddling clothes. The I.D. needed to be removed and reattached every time a baby was changed — a minimum of six times a day — so human error was intrinsic to the system. I witnessed this myself in the hospital when I encountered a sobbing woman with a newborn in her arms who’d returned to report her baby’s name tags didn’t match. “Can’t you tell if it’s your own baby?” asked the administrator, clearly annoyed by her tears. “No!” she cried. “ They all look alike to me!”

Every four hours, babies were routinely rolled in carts from the nursery to their mothers’ room for nursing. The carts were large enough to transport ten to twelve swaddled infants, tightly packed side to side. I would soon be starting my PhD program, so I decided not to nurse Katya. This was very rare in the Soviet Union. With the help of my mother-in-law, I was able to buy Parlodel pills, a foreign–made medication to suppress lactation, and a foreign formula, Similac, both unavailable in pharmacies.

Katya was bottle-fed by the nurses, so I was only permitted to hold her once a day. How eagerly I waited for the nurse to bring her in! While the other mothers nursed, I held Katya in my arms, cherishing every one of the few moments I was allowed to spend with her. As she was tightly swaddled, I couldn’t see her body, but I loved smiling down at her tiny face, grimacing and blowing air bubbles. She never cried, not even once. To me she was simply beautiful.

Except for precious moments with Katya, I was soon bored out of my mind. There was no TV or radio, so women spent the days talking about their deliveries, their husbands, and their other kids. At age 21, I fell in the middle of the pack: four women were older than me (that is to say, in their twenties), and four were still teenagers. The single outlier was thirty-six, and had just given birth to her third child. To give birth in your mid-thirties was all but unheard of for a Soviet woman. The only exception I was aware of was my mother, who had given birth to me at age 35, after her second child, my sister Olga, had died of childhood leukemia at age two. My whole life, my parents kept reminding me that I was a replacement for my middle sister.

We were astounded to learn that the oldest woman was a foreigner. Helen was English, her husband was on the British embassy staff, and their family of four had been living in Moscow for five years. Due to her age, we readily nicknamed her “Babushka.” She was not offended and went along with the joke.

Helen’s Russian was very good, but when I offered to speak English in hope of practicing my language skills, she happily agreed. My first question was why she had chosen to give birth in Moscow instead of England. “Both my children were born in London, so I wanted to have a different experience,” she explained. “It worked out fine: my labor was short and I had an easy delivery.” What she didn’t say was that she’d received special treatment as a foreigner: her husband was allowed to see her in the Director’s Office. He once brought the nurses a big box of Earl Grey tea bags, and Helen kindly asked a nurse to make me a cup. It was so good. That slightly bitter smell of Bergamot was literally and metaphorically from another world!

January 22 came at last, and Katya and I were released from the hospital. Kostya was waiting in the discharge room. We hugged, and I changed into the clothes he’d brought while a nurse I’d never seen before went to get Katya. “It’s freezing outside. Did you bring enough blankets for Katya?” I asked. “Yes, and my father’s here to drive us home.”

Just then, the door opened and the nurse entered with Katya. In keeping with long-standing tradition, she handed the baby to her father: “Here you go, Daddy,” she said, turning sidewise so Kostya could stick money in her pocket — another long-standing tradition. This obligatory “tip” — which was more of a “service fee” for handing over a baby to its father — was well-defined: 15 to 20 rubles for a girl, and 25 to 30 for a boy. For the sake of comparison, I add that Kostya, a 25-year-old junior researcher at the Physics Institute of the Academy of Sciences, earned 140 rubles a month.

Handling Katya as I would a crystal vase, I wrapped her in both of the blankets Kostya had brought, and we stepped outside. After being locked up for a week, inhaling the fresh cold air felt wonderfully invigorating. Kostya’s father met us by the door. “Where’s that little beauty queen?” he asked with a smile, trying to peep under the blanket protecting Katya’s face. “No, no, please wait until we get home,” I begged. “The air’s far too cold for the baby.”

Riding home in the car, I thought about how my mother had spent two whole days on the phone bragging about her first grandchild, my older sister’s daughter. “Natasha did a wonderful job! The baby is picture-perfect — and a healthy size too, 7 ½ pounds. Her skin is flawless! Oh! And you should see her plump little cheeks, so full and round when she’s nursing! Natasha’s going to be an amazing mother!”

What will she say about Katya and me? was all I could think. Katya could not measure up to her cousin’s perfection, and my mother had made it abundantly clear that she highly disapproved of my decision not to nurse. Had she already judged me as a bad mother?

No sooner were we home than my mother arrived. I was so anxious for her admiration that my heart started pounding the minute she walked in the door. I unswaddled Katya for her inspection. She looked much better, but had lost some weight and was now at six pounds. My mother took one glance and gave a little chuckle. “Hmmm! I have never seen such a puny baby. And, as you know, today is your father’s birthday. I have to go right away. Some of his colleagues are coming for dinner, and I’ve got to prepare.” And with that, she left. Expecting worse, I felt relieved.

An hour later, Kostya and his father also returned to work, leaving me with my newborn daughter quietly sleeping in her crib. It was the first time we’d ever been alone together. I listened to her peacefully breathing, my mind swirling with worry. What do I do when she cries? What if she screams and I can’t calm her down? Will she take her formula? What if she chokes?

I soon discovered that caring for an infant took a whole lot of time and work. In my day, for example, babies were still traditionally swaddled because it was thought they felt more secure snuggly wrapped in a blanket. I mastered the technique in a couple of days, but keeping the baby clean was another matter. Traditional flannel receiving blankets, just like those in the States, were used for swaddling. At the very minimum, they had to be changed before every feeding and after every bowel movement. This added up to a good ten soiled blankets, all to be washed at the end of the day.

To make matters worse, commercially made disposable diapers were not yet available in the Soviet Union. We made them ourselves the old-fashioned way, folding cheesecloth eight to ten times over and stitching the layers together by hand. Like most families, we had no washing machine, so every night I hand-washed all the diapers and blankets, wrung them out, and hung them to dry on a line strung up in the kitchen.

All in all, I was fortunate. Katya was an easy baby and we soon established a routine. Though not always willing to eat at designated times, she was a good sleeper. January quickly came to an end, and Kostya took four weeks off in February, the maximum leave allowed for the year, to stay home with the baby so I could return to school. On February 7, the first day of spring semester, I was back in class. By then, I was almost at my pre-pregnancy weight. “Galya, you don’t look like someone who just had a baby three weeks ago!” exclaimed one of my classmates. “How did you do it? Did you just spit it out?”

“It wasn’t quite like spitting,” I replied. “But it was fine.”

*

Public discussion of obstetric abuse is still muzzled in Russia and many other countries, notably including the United States. For stories of “surviving” and “witnessing” such cases, see Birth Monopoly’s “Obstetric Violence Stories Map,” the first worldwide, public database of abusive maternity care stories.

1: The Admissions Entrance to the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow. Source: Google Maps Street View

2: E.V. Radzinsky, “Obstetric aggression,” Status Praesens, Moscow, 2011.

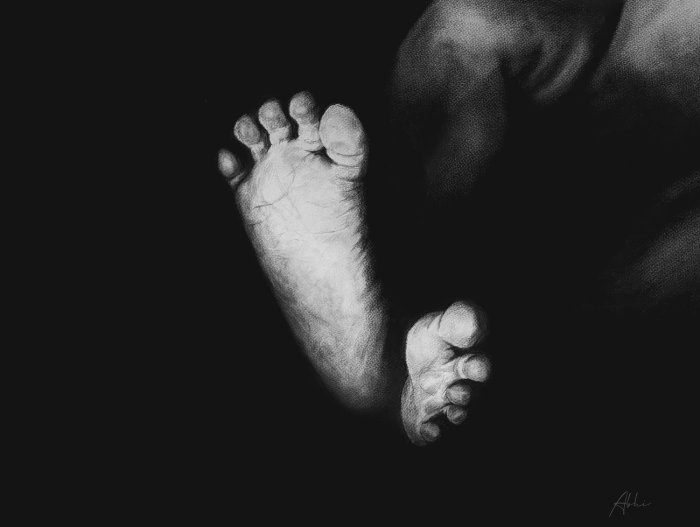

3: Source unknown. Please contact the magazine if you know more about this image.

4: Vladimir Sokolaev, “After Giving Birth,” Novokuznetsk, 1981. Source: russiainphoto.ru

5: Sergey Vassiliev, Delivery Hospital, Chelyabinsk, 1977. Source: russiainphoto.ru

6: Galina Chernaya, “My Baby’s Wrist Tag,” 1982.

7: From: yapet, “My personal USSR. Part I. Maternity hospital,” Livejournal, 2016, yapet.livejournal.com/375257.html

Appeared in Issue Fall '23

Nationality: USA

First Language(s): Russian

Second Language(s):

English

U.S. Embassy Vienna

Listen to Galina Chernaya reading "Hard Labor: Childbirth Soviet Style":

Supported by:

Comments on "Hard Labor: Childbirth Soviet Style"

Please log in to submit a comment.

Login